The Saratoga Campaign Of The American Revolution – Part Five: Second Battle Of Freeman’s Farm

October 19, 2017 by oriskany

Here we are at last, Beasts of War, at the end of our 240th anniversary commemorative series on the Saratoga Campaign. Fought between the forces of the British Crown and American Patriot rebels, the Saratoga campaign was fought in July-October 1777 and changed the course of the American Revolution.

If you’re just joining us, please take a moment to check out and comment on some of our previous instalments, which outline how we’ve come to this momentous and climactic juncture:

- Part One: Invasion Plan & Opening Battles

- Part Two: Battle of Oriskany

- Part Three: Battle of Bennington

- Part Four: First Battle of Freeman’s Farm

Now it’s time to bring down the curtain on this saga, and look at how America’s fortunes turned once and for all in their war for independence.

Burgoyne Takes Stock

Where Did It All Go Wrong?

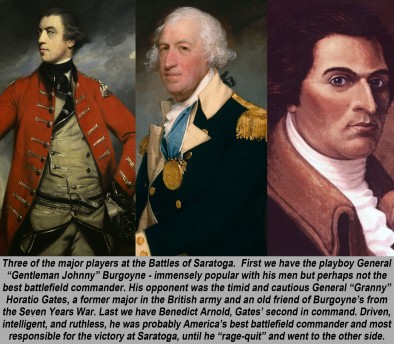

For the British commander here in upstate New York, General “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne, things haven’t exactly worked out as he planned. His 1777 invasion of New York, pushing down from Canada through Lake Champlain and on to the Hudson River, has been let down by failed supporting drives from the west and New York City to the south.

Left on his own, he’s marched down the Hudson River anyway, intent on reaching Albany, the capital of New York. From here he hoped to split the most rebellious colonies of New England off from the rest of country, and thus divide and conquer this troublesome American rebellion.

But through the Battles of Hubbardton (July 7th), Oriskany (August 6th), and Bennington (August 16th), things steadily got worse for Gentleman Johnny.

His American loyalists and Iroquois have largely deserted, while Patriot militias have swarmed to the rebel cause after threats of Indian raids.

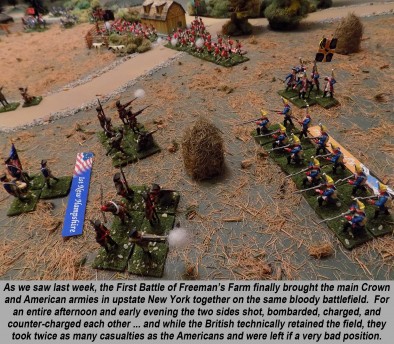

Let down by his fellow British generals, his American Loyalists, his Iroquois allies, Burgoyne nevertheless tried to shove his weakened army around and past the fortified American position at Bemis Heights, triggering the First Battle of Freeman’s Farm on September 19, 1777.

While Burgoyne technically held the field, he lost twice as many troops as the Americans, and he’s no closer to actually getting past the main American position and marching on Albany.

Meanwhile, his army continues to weaken through disease and desertion, while the Americans grow stronger with more militias joining every day.

A final ray of hope is snuffed out when General Henry Clinton, commanding British troops in New York City, finally sends a small force to invade up the Hudson. There’s a little fighting near Fort Montgomery, but never enough to help Burgoyne at Saratoga. Gentleman Johnny is truly on his own.

Trouble In The American Camp

Never Enough Drama ...

After the First Battle of Freeman’s Farm, you’d think all would be peachy in the American camp. They’re well-fortified on high ground, blocking Burgoyne’s only possible route of advance, they outnumber the British and Germans over two-to-one, and the Americans are growing stronger every day.

But these are Americans, and so are legally required to argue about something. Here the bone of contention lies between the two American commanders, Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold. Gates is technically in command, but is furious with Arnold for winning the First Battle of Freeman’s Farm … without Gates’ permission.

Now Arnold wants to hit Burgoyne again. This is only natural, Arnold is an aggressive tactician and born battlefield commander. Things are also going very badly for the Americans elsewhere in the war. Hundreds of miles away, Washington has just lost the Battles of Brandywine (Sept 11th), Paoli (Sept 20th), and Germantown (Oct 4th).

Even worse, the American capital, Philadelphia, has fallen to the British. By all rights, the war is already over … with a solid British victory. So if the Americans ever needed a redeeming victory, it’s now. But Gates won’t let Arnold attack, convinced Burgoyne will attack first.

Gates and Burgoyne know each other, remember, old friends from the Seven Years War. “Perhaps his despair will dictate him to risk all upon one throw,” Gates writes. “He [Burgoyne] is an old gamester, and in his time has known many chances.”

I’m not going to lie, I despise “Granny” Gates, but on this occasion he is absolutely right. Perhaps out of desperation, delusion, or simply to put himself out of his own misery, Burgoyne gathers everything he has left and strikes on October 7th, 1777. The Second Battle of Freeman’s Farm has begun.

Second Freeman’s Farm

If At First You Don’t Succeed…Fail, Fail Again

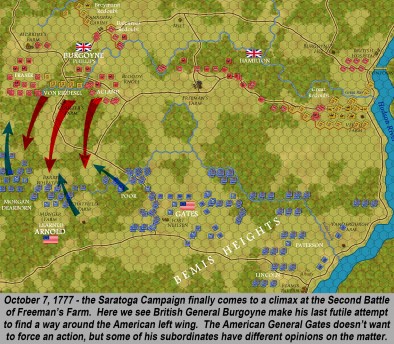

Again, Burgoyne throws his weight to the west, hoping to hedge around the American left wing. His plan is half-hearted at best, basically a “reconnaissance in force.” But if the situation gets too thick, the British will fall back and maybe start a limited withdrawal up the Hudson.

Such a plan hardly inspires confidence in the officers or men. Yet the regiments form up in a heavy autumn mist and march out at around 10:00. Major Acland, with a heavy force of British grenadiers, leads on the left. Von Riedesel commands Germans in the centre and Fraser leads light infantry and the 24th Regiment of Foot on the British right.

Together this force totals about 1700, and heads toward the western end of the American position. The mood is hardly a good one, everyone knows this force is too small to fight a pitched battle, and too big to hide from enemy pickets. When they run into the Americans, there’s going to be hell to pay.

In the American camp, General Gates and his officers are enjoying a lunch of ox heart when the first snaps of musketry start echoing through the woods. Brusquely Arnold demands that permission to attack. Gates refuses. Arnold presses. Finally Gates loses his patience, fires Arnold, and sends him to sulk in his sent.

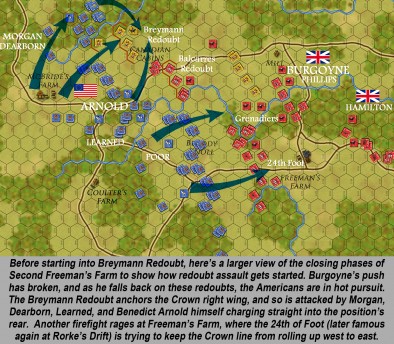

Instead, General Benjamin Lincoln is sent forward with General Poor’s brigade, along with Morgan’s riflemen and Henry Dearborn’s supporting light infantry. General Learned’s brigade is sent up as a reserve.

Confined to his tent like a five-year old, Arnold fumes and by some accounts, starts drinking heavily. As the sounds of the battle draw closer, Arnold finally loses what remains of his temper. Storming out of his tent and draining a final tankard of New England rum, he “borrows” someone’s horse and rides out to the fight.

Completely without military authority or any kind of lawful command, Arnold rides out behind a line of Connecticut militia (he’s from Connecticut himself) and basically steals command of Learned’s brigade (which is still in reserve). Learned goes with it, he’s an easy-going guy his men positively love Arnold, the hard-charging hero.

Arnold and his stolen brigade hits the advancing British columns at Barber’s Wheatfield, and that’s the end of Burgoyne’s “reconnaissance in force.” British and German casualties are horrific, and what’s left of their regiments start to withdraw.

So intense is the fire, in fact, that Burgoyne’s waistcoat is shot through, his horse is shot from under him, and his hat is shot away. Say what you will about the “playboy general,” but Burgoyne is no coward. Yet Gentleman Johnny’s gambler’s luck holds out, and he’s never hit himself. Other generals, however, aren’t so lucky.

Brigadier-General Simon Fraser’s force is covering the British retreat. The Scotsman Fraser is among Burgoyne’s best commanders, having placed the guns that took Fort Ticonderoga, won the Battle of Hubbardton, and commanded the advanced corps through the course of this whole campaign.

But Timothy Murphy, one of Morgan’s riflemen, has Fraser in his sights. After two near-misses, his men beg him to fall back, but Fraser refuses. Murphy’s third bullet hits Fraser through the bowels. He will die in agony early the next morning.

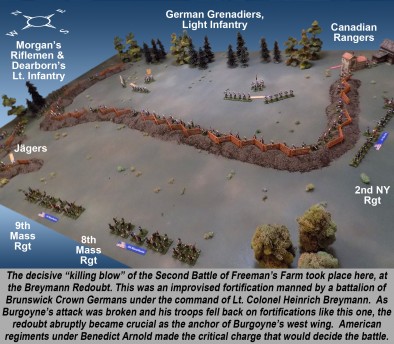

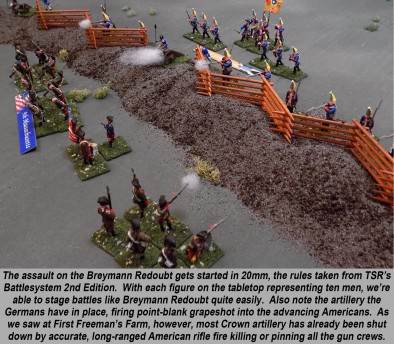

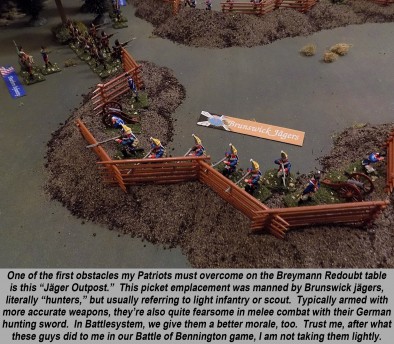

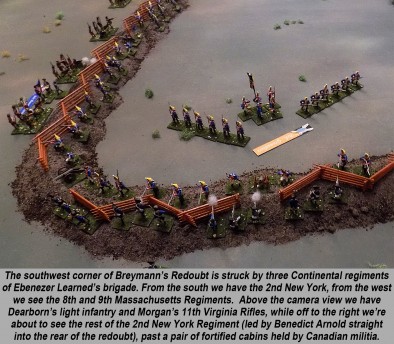

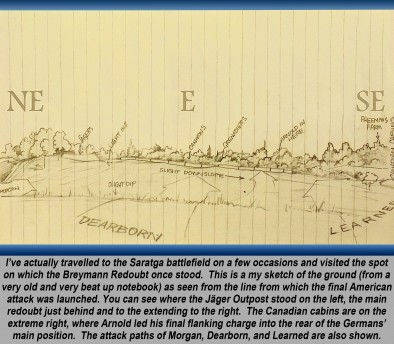

The British line comes apart, Arnold leading the Americans in a wheeling motion around Burgoyne’s west wing. Here the ground is held by more Germans, including a redoubt anchoring the Crown’s far right wing commanded by Lt. Colonel Heinrich Breymann. If this “Breymann Redoubt” falls, so does Burgoyne’s whole line.

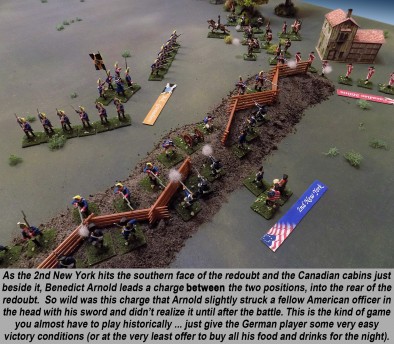

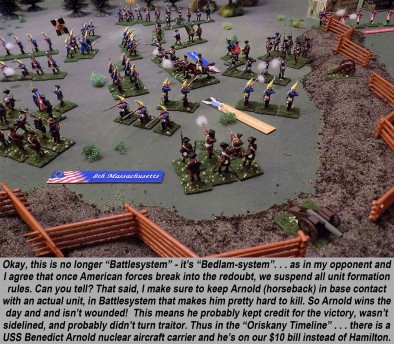

Arnold sees this, and immediately leads a climactic charge. Morgan and Dearborn’s troops hit the redoubt from the right, Learned’s men hit the redoubt’s front and left, and Arnold himself leads troops straight into the rear of this key position. The redoubt is in chaos, and Breymann will wind up dead, shot in the back by one of his own men.

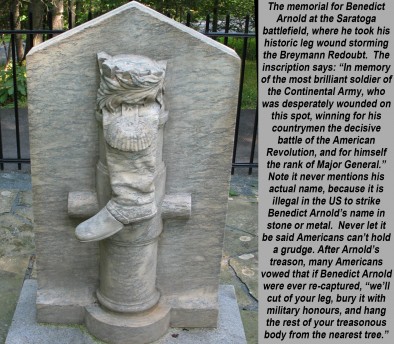

Yet it is also at this moment of supreme triumph that Arnold himself is hideously wounded. A bullet smashes through his thigh and kills his borrowed horse. As the horse falls, it further shatters Arnold’s wounded leg. It will be three months before he can sit up in bed, and nine months before he re-joins the army.

Still, the battle is over. With his wing gone, Burgoyne must fall back to a small pocket by the Hudson River. That night, be begins his retreat. Yet even this is soon denied him as yet over 5000 of his men are forced to surrender.

Saratoga - Conclusions

What Did This All Mean?

The impact that this campaign has on the course of the American Revolution, and by extension, world history, is difficult to overstate. Although it takes months for the news to cross the Atlantic, once American and French ambassadors learn of this victory, they are finally able to sign an alliance between America and King Louis XVI.

With France in the war on America’s side, victory in the Revolution becomes possible. Britain’s focus in the war abruptly changes, and they withdraw from Philadelphia (the American capital) the next spring.

The war shifts largely to the Caribbean and the American south, there the Battle of Yorktown will win the war for America in late 1781.

Burgoyne will eventually return to Great Britain, where he will be forgiven (to an extent) for this turn of events. History is less kind to Horatio Gates, who unfairly gets the credit for Saratoga. He is defeated and humiliated at the Battle of Camden, South Carolina in 1780, personally fleeing the field in terrified disgrace. He is never forgiven.

Worst of all, however, is Benedict Arnold. After an agonizing recovery, he not only lives but miraculously keeps his leg. Gates has stolen the glory for Saratoga, however, and yet again Arnold is slighted, overlooked for promotion, and actually brought to trial by political enemies in Congress.

It’s all too much. Hurt and angered by a country and a government he sees as supremely ungrateful, one of America’s greatest heroes makes the tragic mistake of turning to the other side. He never accomplishes much as a British general, and dies in obscurity in London in 1801.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this series on the Saratoga Campaign. I’d like to thank Justin and Az for the great interview, Lance and Ben and Tom Guthrie for the help with publication and web layout, and Warren and the team for letting me publish on the Beasts of War site.

As always, my greatest thanks goes to all of you who take the time to read and leave a comment on these article threads. With your help, we can keep working to ensure a strong historical wargaming presence here in the community. Thanks so much, and I hope to see you next time.

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"As the sounds of the battle draw closer, Arnold finally loses what remains of his temper..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"History is less kind to Horatio Gates, who unfairly gets the credit for Saratoga..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Alternative Trench Crusade Miniatures? Trench Missionaries Review | Wargames Atlantic [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-trench-missionaries-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![10mm Medieval Miniatures! Azincourt English Army Review | Wargames Atlantic [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-azincourt-english-army-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![StarCraft Tabletop Miniatures Game Pre-Orders Live Now [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/starcraft-tmg-news-cover-600-338.jpg)

![Mounted US Cavalry On Kickstarter For Dead Man’s Hand! [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/us-cavalry-main-600-338.jpg)

![Play WW2 Commando Operations With Butcher & Bolt [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/relaunch-600-338.jpg)

Another good read. Benedict Arnold really does beg the question ‘hero or villain?’, was it ego or genuine grievance with the revolutionary cause that drove his betrayal? Definitely worth some more reading.

@oriskany, this has been a great series, clearly a work of personal passion, thank you for the effort you put in to it.

That’s a very deep and controversial story.

Basically Arnold never got the respect he believed he deserved, others were constantly slighting him, The Governor of Pennsylvanian started attacking him for no reason.

Basically the Crux is, Arnold is accused of war profiteering by the Governor of Pennsylvanian who threatened to pull his states financial and material support for the War if Arnold wasn’t punished. Congress holds an inquiry and finds him innocent of all charges but he still faces a Military Trial/Court Martial which Washington (under pressure) defers indefinitely meaning Arnold is essentially being punished without trial. He demands a trail, is refused and starts contacting the British. Washington comes to him later on and offers him command of an army but he’s already gone too deep and instead gets command over Fort Arnold (named after him and today called West Point) which he began to weaken but before he could execute the plan his contact was executed and the plan was revealed.

Thanks very much, @damon – @elessar2590 gives the details of the eventual betrayal quite well. Honestly I feel the motivation goes back to as early as Ticonderoga (May 1775) when he really commanded the seizure of the fort (admittedly with Ethan Allen’s men) but Ethan Allen got most of the credit for political purposes – they were still trying to get Vermont into the war on the colonial side.

So a lot of it was grievance. A lot of it was definitely ego. Arnold was something of a drama queen. 😀 Easily insulted, quick to anger, and saw almost everything that happened as an affront to his personal honor (probably an inferiority complex brought on by his drunken, destitute father).

Thanks @elessar2590 – I think you got events around Arnold from 1778-80 damned near perfect. I would add that what we would call “War Profiteering” today was a widely accepted process, especially since the Continental Congress couldn’t actually pay any of the soldiers or officers. It was assumed that officers were gentlemen that would show restraint in doing what was required to get by.

Even my other favorite AWI General Nathaniel Greene, the Quaker, was deep, DEEP into this kind of activity.

Arnold might have gone a little overboard when he purchased that enormous estate in Philadelphia when Washington made him military governor following the British withdrawal in early 78. The idea was to give Arnold an important and prestigious post that didn’t actually require any hard field duty, while his leg healed. Instead Arnold went a little too deep into “war profiteering,” and of course married the gorgeous Peggy Shippen (from a very VERY Loyalist family).

Also, although war profiteering was more or less accepted, whenever someone had a problem with you politically, it would make a convenient foil with which to attack your reputation.

Absolutely the practice was universal, close the stores, take stock of everything then make a few buck by letting the right people see the books before anyone else.

Oops I accidentally left out the ego bit. Basically if you were an ambitious officer, like Arnold, you were a image obsessed and acted like a teenage girl craving your superiors attention so you’d get promoted into a cushy job and could sell you commission for more money.

Shippen was also half his age so Arnold must have had some game. She was also a very good businesswoman and very well connected as you said. He was also given a huge amount of money to defect, I think 10,000 pounds which roughly translates to about 100 Million Pounds in current money, more than enough to purchase a Colonelcy of the Foot Guard with change left over, it definitely played a part.

Yes, Arnold was 38 at the time, Shippen was 18 or 19. Definitely a sharp woman, intelligent and savvy, and by all accounts drop-dead beautiful. Of course there were no cameras at the time, but this is how she’s described by just about everyone who met her, up to and including George Washington himself.

Yes, she had Washington wrapped around her finger as well – as evidenced by how she was able to talk her way out of being arrested after being left behind by Arnold when his plot was exposed.

Wow what a conclusion! Bravo @oriskany.

Thanks very much, sir. 😀 Coming from a fellow “student and expert of the period,” that means a lot. 😀

Wow BA really spat his dummy out of the pram, “no one man” and all that.

Awesome series, Lloyd would be proud of your use of skewers!

What’s next then Jim?

Yes, @bonesbs – something like 300 toothpicks were used in the making of all those redoubt fences. 😀

Not sure what will be coming up next, to be honest. 😀

Great wrap up, I almost wish real life had mirrored your game. I would be curious what actual history that might have changed. I have to admit I am ALMOST sad to see the article series end. I liked seeing figures I worked on, on the site, and learning a little about history. However, I will not be sad to get my dining room table back and I will not miss having to sweep up dirt from those admittedly cool looking redoubts.

Hey, I sweep up my own “redoubt dirt” @gladesrunner ! 😀

To be honest, I think we’re ending it at just the right time. If you’re not a LITTLE sorry to see it end, you may not have enjoyed what you were working on the first place. If you’re not a LITTLE glad to see it end, you may not have given it your all.

Some of those British and German troops need a bit of a touch up, though. With the articles finished maybe I’ll be able to get some actual hobby time to finish those up. 😀

Truly great series @oriskany. I don’t seem able to resist a fight in the forest. I find it interesting the the second battle of Freeman’s Farm was forced as the campaigning season should have been over by Autumn. The British food stocks must have been scraping the bottom of the barrels and would be adding to the desertions, surely.

The age difference between Benedict Arnold and Shippen are about right for the marriage customs of the day in high society.

Perhaps one more thing should be considered about Benedict Arnold is the length of intense pain he went through with his wound. He had a short temper that would have a negative effect on recovery. He was more than likely highly depressed, festering feelings of being owed, robbed and feelings of his career being over with no chance left to fill the field of glory eating away at him. Something an ego like his could not bear. Most would go insane and I doubt that he was of sound mind. Certainly it was not the times to marry from the wrong side of the fence either. If Shippen was even half as good looking as history tells, then in this state of mind Arnold could have easily have been lead down the wrong path. I am trying to see the person here and not the cardboard cutout of history. He was a passionate patriot yet he took a 180′ turn. What went wrong or what snapped? So don’t get me wrong, I am not trying to start up a we love Benedict club.

Absolutely agree, @jamesevans140 – on the complexity of Arnold and what he was going through and what may have motivated the decisions he eventually made.

He probably did prolong his recovery from the wound by insisting that he keep his leg (can’t really blame him on that one) and by pushing his recovery faster than was prudent.

Watching his mortal enemy Gates waltz away with the glory and credit for the victory he had won and was living in agony for couldn’t have helped.

Gates was (at the time) something of a political darling with the Continental Congress … to the point where many wanted to have Washington replaced with Gates. So Arnold’s antipathy with Gates probably contributed to Washington’s respect and friendship with Arnold to a degree. Even during the whole Philadelphia courts-martial mentioned by @elessar2590 above, Washington was getting ready to give Arnold the command of the Continental Army’s left wing, basically making him second in command of the army (and thus promoting Arnold past perhaps a dozen other major-generals).

I would also agree that we don’t start an Arnold fan club. A great many American generals were treated very shabbily during this war – American citizens and Congress at the time were still balking at the idea of a standing army AT ALL, or even the notion of a federal government. Some stuck with it (Nathaniel Greene, Sullivan, Wayne, and many others), some decided to quit (John Stark, Putnam, Morgan).

But only one quit … and then joined the other side, WHILE trying to sell what was probably the most important single installation to the British. If Arnold had succeeded in giving Fort Arnold (West Point) to the British, that would have given them the Hudson River as well. This equates essentially to handing the British the victory that Burgoyne had failed to achieve in the whole 1777 campaign … without firing a shot.

I dunno, some days I love Arnold (or at least empathize with him), some days I despise him. He’s a cautionary tale. And he’s just so damned INTERESTING to study from a comfortable and objective distance. His post-war career during the 1780s and 1790s is great, basically a pirate, blockade runner, and privateer working for the Crown between the Caribbean and London.

a doomed desperate advance needing a miracle to accomplish to any degree of success.

Thanks @zorg – I think we’ve all been there on the wargaming table. You find yourself in a position with NO “right” answers, and you just have to pick one and hope for the best.

on the table and in life we can have the win/win or the lose/lose in some situation’s flung at you from a bad dice or life just being a pain in the ass, Lol

Can’t argue with that. 😀

Great read – If Johnny had pulled out in time, and let Washington loose the war down south … We might have been like Canada. ..

Not outside the realm of possibility, @rasmus . Burgoyne accepts a draw and pulls back to Fort Edward or even Fort Ticonderoga (probably before Bennington). Washington loses all those big battles in the south and Philadelphia. With no Saratoga victory, Ben Franklin STILL can’t get a deal with the French, so they never enter the war, the British never have to pull out of Philadelphia, etc etc etc …

@rasmus By “might have been like Canada,” do you mean “filled with Syrians”?

He may have meant “more polite than Americans” and “with a much better president.” 🙂

The Crown snatching defeat from the jaws of victory

Thanks, @rasmus . With early victories in this campaign like Ticonderoga and Hubbardton, it kind of looks like Burgoyne was running away with a campaign victory in the summer of 1777, only to lose it through bad luck and decisions later. Then again, his overall plan really depended on Howe or Clinton coming up from New York City to help, which we know in hindsight was never going to happen. So we almost come to the conclusion that Burgoyne’s invasion was doomed from the start? At least from certain perspectives? 🙂

Great series of articles. I love the historical retrospectives you have put together.

Thanks very much, @cbrenner. 🙂 Glad you liked them!

Interesting summary on the BA story, thank you chaps. Looks like an interesting study into the motives for treason, several layers to dig through there. Is the motivation idealistic or egotistical?

‘This cause is no longer deserving of support’ or ‘screw you guys, I’m in this for me’, or a combination?

For years I always heard ‘Benedict Arnold’ and ‘bastard’ mentioned in the same sentence, but didn’t much about the circumstances surrounding his turncoat decision. Makes sense now… a bit extreme of course, a decision seemingly driven by ego.

Great battle report @oriskany .

Indeed, @cpauls1 – there’s a little bit of logic to it. Actually a lot. And if Arnold has simply quit (as so many other American officers did when they got tired on how they were being treated), I firmly believe Arnold’s place in our history would be secure (if not stellar). Examples we can cite, again, include guys like Stark, Putnam, Morgan …

Or hell, even guys like General John Glover, who quit along with his whole brigade of “Marbleheaders” from Massachusetts, to become privateers instead of soldiers (at least privateers make money).

But when you get your panties wound up in such a bunch that that you actually put on a red coat? That’s crossing a whole lot of lines.

A big part of it is what Arnold as literally one of the best we had. When a schmuck quits or even turns traitor, you’re like: “good riddance.” But like Washington said himself that day by the Hudson River:

“Arnold has betrayed us. Who can we trust now?”

Yeah, there’s a fine line between figuring out a man’s motivation, background, context, and trying understand why he did something … And empathizing with him to the point where you “forgive” him. Almost like Confederate ACW generals or German generals in WW2. Try to understand – and not condone.

I still have a lot of issues about any judgement of Benedict Arnold due to the the times themselves. This is a crucible time to live in and it where the American identity will be cast. Yet here the crucible is still being filled.

I would through the glasses of the times would call this a civil war. Both sides consider themselves British caught on the question of government without representation or the idea of self government as a dominion. Like all political questions it will eventually polarize to two factions. In this view the notion of treason becomes somewhat questionable. One pole has declared independence from the crown and the other pole does not want it. Why were those who fought against independence not rounded up afterwards and hung as traitors? We see evidence of a knives out political attack on Benedict Arnold was he as being labeled a traitor their final political victory and his removal from local politics. As a traitor Washington and other friends are now powerless to help him. Due to the distance of time we may never be able to reconstruct what the politics were about, the reason for it and those involved. All we can say is that others saw him as a blockage, threat or both and that they wanted him removed. They succeeded in a total victory and as such own and wrote the history. As for his career after the war I see it as being something of the times. Most were pirates and robbers in one way or another. It just depends on who has power and which side their decide the law will take.

Given all this I find it difficult to set my moral compass. These are truly amazing times with most things in flux creating some amazing people that are great to research.

You bring up some great points, @jamesevans140 . I even agree with some of them. 😀

Please forgive my snarky sense of humor. I’m just back from work and a lot of travel this week. Did get to meet some members from the Beasts of War community who were visiting the US, though.

😀

Okay:

I still have a lot of issues about any judgement of Benedict Arnold due to the the times themselves.

I would agree with that up to about 95% … the way he was treated by the other generals, treated by the press, treated by his home state, and especially treated by Congress. Up until then, I’m totally with him. Right up to the point where he tries to sell West Point for 20,000 pounds, switches armies, abandons his wife and child, puts on the other uniform, and takes up arms against his former comrades.

Now, I am judging. 😀

I would through the glasses of the times would call this a civil war.

That’s an often-quoted idea that … always brings up my hackles just a little. I won’t say it’s wrong. It’s just dangerously incomplete.

Both sides consider themselves British caught on the question of government without representation or the idea of self government as a dominion.

That’s the part that “destabilizes” the previous statement. The whole idea was this war was about taxation or political representation or where the colonies fit into the larger framework of Empire or Dominion or whatever they were calling that week … that was pure Patriot propaganda – a slogan no one in the Patriot or even Loyalist camp ever wanted fulfilled. Historian Thomas Fleming writes that when Franklin was sent to London before the war to negotiate for Pennsylvania, Georgia, and really all of the colonies, he was told in no uncertain terms that in NO WAY should he ever accept a deal for representation in either house of the British Parliament. That was a smokescreen meant to imbue the Patriot movement with a sense of legitimacy and moderation that really wasn’t there at the time.

The Patriots who made up one side of this war did not, not, not consider themselves British. They hadn’t for generations. The Loyalists certainly did, and that’s why I’m not saying what you post is “wrong.” And when the Patriots and Loyalists fought each other (and Lord, did they ever), yes, THAT part starts to resemble a civil war. Again, not wrong, just … not complete, and leaving out the more important part of the picture, I feel.

Why were those who fought against independence not rounded up afterwards and hung as traitors?

A lot of them were, actually. 🙁

Most were pirates and robbers in one way or another. It just depends on who has power and which side their decide the law will take.

Absolutely agree with that. I was making that point earlier where “war profiteering” was … sort of “quietly allowed,” and almost expected, especially in an army where Congress couldn’t pay army salaries. Then again, if you rubbed someone the wrong way, that “war profiteering” card could always be hauled out by your political enemies, as it was with Arnold.

I personally have no trouble with my moral compass on this issue. Arnold was one of the best we had and was treated terribly by just about everyone. If he had quit, gone privateer, or simply rode out the rest of the war on “cushy” assignments like Philadelphia or West Point, I (and American history in general) would have no problem. In fact, I’m usually the guy defending Arnold up to a point. 😀

It’s when you actively conspire with an enemy state, not only to join them yourself, but to systematically and methodically weaken what is probably the most important military installation on the continent at the time (under your command), hand over plans to that fort, and send most of that fort’s garrison off on “detached duty” so you you can “sell” it to the enemy for 20,000 sterling …

Then get caught, and abandon your wife and child in your escape … not to mention the guy helping you make this deal so he’s hung in your place (Captain John Andre) …

And maybe for me, and others who’ve been in the military, this is less about betraying your country than it is betraying your army and your comrades. Those men at West Point looked up to him as their commander and the Hero of Saratoga. They’d have died on British prison ships if his plan had worked.

“I personally have no trouble with my moral compass on this issue. Arnold was one of the best we had and was treated terribly by just about everyone. If he had quit, gone privateer, or simply rode out the rest of the war on “cushy” assignments like Philadelphia or West Point, I (and American history in general) would have no problem”

OK, could BA have come to regard the hierarchy of the revolution as his enemies, certainly seems he was ostracised to the point of being a pariah to elements of the Continental government, even his ‘friends’ (Washington) wouldn’t publicly support him? Could this lead him to justify his actions to himself, ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend?’ Not trying to defend his choice, just trying to rationalise how a man could justify the extent of this betrayal to himself.

“It’s when you actively conspire with an enemy state, not only to join them yourself, but to systematically and methodically weaken what is probably the most important military installation on the continent at the time (under your command), hand over plans to that fort, and send most of that fort’s garrison off on “detached duty” so you you can “sell” it to the enemy for 20,000 sterling …

Then get caught, and abandon your wife and child in your escape … not to mention the guy helping you make this deal so he’s hung in your place (Captain John Andre) …”

But this makes it look more like ego-mania with possible psychopathic tendencies; a person who has no feeling for other people, does not think about the future, and does not feel bad about anything they have done in the past.

Honestly, @damon – I think Benedict Arnold also had a big streak of good ole’ selfishness in him. A lot of the successes he scored for the Patriot cause early in the war were, at least in part, to win glory and respect (and yes, money) for himself. And when he didn’t get it in the proportions he thought due to him, he went shopping somewhere else.

Not to get too analytical about it (I’m certainly no psychiatrist) but some of this might have come from his childhood, where his father (a respected merchant in New London, CT) wound up drinking himself into oblivion, ruining his reputation and putting his family into poverty. In those days in America, one’s reputation was as vital as it was irreparable once damaged. Arnold worked himself up off the shit-heap as an apothecary’s apprentice, became a modestly successful merchant on his own, and when the war came, saw it as a chance to really make a name for himself (as he’d seen his father lose his). When your background is one of “scarcity,” be it money, reputation, emotional support, or whatever, there’s a chance you can get very jealous of protective of whatever scraps you manage to put together later in life. Sadly, this makes some people very selfish / paranoid / protective / jealous later in life.

Then the Continental Congress started going after him 1778-79, he might have seen echoes of what had happened to his father happening to him. Fear-driven selfishness, combined with an inferiority complex, might have had a hand in his choices.

Some people say Peggy Shippen’s whispering also had an influence, I’ve never really known about that.

All interesting stuff, a subject definitely worth more reading about.

Wouldn’t historians love to find a lost journal or letter; “Why I Did It”. Although it doesn’t seem he was given to self reflection or introspection beyond ‘what’s in it for me?’

Oh, I’ve read plenty (Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor – Willard Sterne Randall) but I don’t think people will ever really know the full story. A lot of this happened by the fireside of that Philadelphia mansion and in the bedroom with Peggy Shippen (***sigh***). Sadly, no one was writing any of it down. Obviously he left American after the war, and even back in England he was never really accepted and no one wanted to hear what he had to say. So I’m afraid this will largely be one of those things …

Silly thought probably but here goes. Can you because traitor if the country who you allegedly committed acts of treason against doesn’t exist?

Actually, it did exist, as established by the Declaration of Independence, 4 July 1776. 😀

To say nothing of betraying the Continental Army, established November 1775.

Told you it was silly

No question or opinion is silly. Well, not in the historical forums. 😀

I’m sure if the war had turned out different the Treaty of Paris (if there even would have been a treaty with “crushed rebels” would have invalidated Declaration of the Independence, except the signatures could have been used as a checklist for the hangman.

“Okay, let’s see. John Hancock …”

Thud-snap of the gallows.

“One down, 55 to go …”

Interesting comments @oriskany.

My points I make I try to filter back to the time and place without the modern baggage we bring along with us. That is why I call the fort, Fort Arnold as it has for now none of the significance of the latter West Point other than its defensive value.

Australia is a socialist democratic dominion of England. Twice in my life I have witnessed a referendum for it to be a republic. These were argumentative violent times when a tiny amount of people died for their views. I don’t believe anything is straight forward and there is always an agenda not to far away. Out here the vote for a republic will never succeed until some fundamentals are sorted first. Do we wish to leave the British empire? Do we wish to remain in the British Commonwealth? These are two very different questions. Do we wish to remain socialist? Which model of republication do we want. Until these four issues are solved it will not happen. In the last referendum the government had an agenda as it asked if we wish to remain as we are or did we want the least favored non socialist republic model. Being a socialist in your halls of government make me a pinko red loving democracy hating anti capitalist back stabbing communist. All of which you know not to be true.

I believe Arnold had snapped just prior to his appointment to fort Arnold after that in his festering mind it was of payback and hurt for what he perceived had been unjustly did to him. He was of course a self serving egotistical person with little regard for anyone else. I make no attempt to say good of this bad part of his personality. I believe he would be a nasty bad of goods if he thought you had crossed him and would disregard anyone he believed was inferior, including commanding officers.

Completely agree that the points I raised are incomplete just missing the mark. However calling it a mere war of independence just falls short of the mark as well. Their are also many that would have used the situation as a smoke screen to settle old scores and others who took one side or the other for pure profit. All this makes it an interesting study. I am not saying this applies to Arnold but in wars where everyone is not sneaky clean the best method to put all knives to bed is to assign all blame to a single person or small group so ill feelings can be safely vented. However Arnold with his amoral behavior does make him a wonderful candidate.

Great post again, @jamesevans140 –

I would argue that West Point (or Fort Arnold, if you prefer) was at the time the most important single military point in North America. It was part of a complex that included Fort Independence right across the Hudson River, and absolutely bottlenecked the Hudson River (most important river in America at the time). The Hudson has something of a dog-leg in its course there, where ships of the time cannot simply sail past, but put out longboats and have to paddle around it. This, plus the chain, plus the massed artillery, meant that the only way the Americans could keep the dominant Royal Navy from controlling the whole river (and thus splitting the American Colonies in half) was to hold that fort (Forts Washington and Lee were already gone, and Fort Montgomery was already under threat and not doing very much in the wake of Gen Henry Clinton’s limited offensive of 1777).

If Arnold gives up that fort, he gives up everything the Saratoga Campaign was fought over two years before, all of New England, and most of New York. Basically, the northern half of the country.

That’s the truth of the time.

I believe Arnold had snapped just prior to his appointment to Fort Arnold

That I would agree with, seeing as this was shortly after the Philadelphia courts-martial that I think largely pushed Arnold over the edge.

After that in his festering mind it was of payback and hurt for what he perceived had been unjustly did to him.

Yes.

He was of course a self serving egotistical person with little regard for anyone else.

I admire a lot of things about the man, but this almost Shakespearean “tragic flaw” is undeniable.

However calling it a mere war of independence just falls short of the mark as well.

I couldn’t agree more. This is why I get slightly riled when people insist on calling it the American War of Independence. We call it the American Revolution. We conceived it, we started it, we won it, we get to name it, as 10,000 American history professors here call it.. 😀 Furthermore, I think the “Revolution” title is more accurate since it captures some of the internal civil war aspect of it as well.

Their are also many that would have used the situation as a smoke screen to settle old scores and others who took one side or the other for pure profit.

Oh, this was SOOOO the case in the south. Didn’t mention it in the article series because it was out of scope, but once the war moves into Georgia and the Carolinas starting in 1779, it becomes a very nasty affair with many people settling feuds and scores under the guise of patriotism or loyalty to the Crown. Ironically, it’s mostly the rich, established blue-blood families that are the patriots (families that have been here 100-150 years who no longer consider themselves British) against the poor, struggling, recent immigrants from England and Scotland who still see themselves as British subjects and thus remain Loyalist. THIS is where it gets nasty and much more of a “civil war.”

There is not such thing as a silly question, just silly answers. 😉

So you’re saying my answers are silly, now? Just kidding of course. 😀 😀 😀 I would actually agree with that statement. No harm can come from asking a question, it’s if the answer is not carefully considered that things can go pear-shaped.

That’s not stopped 95% of the opinions on the internet!!!

Dammit, why won’t my smileys work?!

“That’s not stopped 95% of the opinions on the internet!!!”

That’s why I tend to stuck with Beasts of War – it’s a pretty polite and respectful community most of the time – unlike most others. 😀

Here are some extra smiles:

🙂 🙂 🙂

@damon remember empty vessels make the most noise.

They become the background noise you learn to ignore.

@oriskany what other campaigns of the AWI would you suggest as interesting for wargaming purposes?

That’s a great question, @jamesevans140 . For years now I’ve wondered why the American Revolution doesn’t get more focus here in the US among wargamers (black powder fans in the US seem obsessed with the Civil War). After two article series I think I’m starting to figure out why this is. Most battles in the American Revolution are so uneven, and you have to be so careful with asymmetric victory conditions, that they’re actually pretty hard to do many times.

Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan vs. Cornwallis and Banastre Tarleton would be my best guess for another campaign where the battles are small, fun, interesting, and somewhat balanced. You have plenty of Crown victories like Camden, plenty of Patriot victories like Cowpens, and mixed-result free-for-alls like Guildford Courthouse. And unlike these northern battles around Saratoga, you have lots of cavalry in the southern battles, including the aforementioned Tarleton and Colonel William Washington (George Washington’s cousin). :D.

Thanks for your reply @oriskany. I think the ACW gets more interest simple because it is closer time wise. Most Americans I have met have family stories of what they did in the civil war. While very few from the AWI where these stories have fallen into myth and legend which for family stories is the waste paper basket of history. The other thing is that the ACW is normally divided into east and west. From forested mountains to the knee high shrub lands of Texas. As long as you don’t nameplate each regiment you get a lot of bang for your buck for your armies. The issue for AWI as taught today seem to more brushed over and single point commentary. This may be different in the U.S. I know Cowpens for its one point, uniforms. It was hot and the British were wearing their European uniforms and not tropical dress while the Americans were dressed for the climate. So the British soldiers were falling fast by mid afternoon from sun stroke. I really only had to know this to pass my history test and of course that Benedict Arnold was a black hearted, sellout traitor.

Your article series showed a different light to Saratoga than my history teacher did. Just the names of the battles, the generals and who won. Yet I find it is a wonderful study of warfare in the forested hill and mountain terrain and more than a turning point campaign, which is really all I had to remember for my history test. So it interested me enough to read more, just a thin Osprey. Even this suggested you could get bang for your buck as I believe that in wargaming today the days of building an army just to fight Waterloo or Gettysburg are over. The current state of wargaming is for the feel and not just a historical replay, hence pick up points based gaming. For those that wish to wargame in this modern way I believed the AWI offers a great black powder gaming experience but I lack your knowledge of the AWI to point this out.

Thank you so kindly for your great reply @elessar2590. As I mentioned before I am on shaky ground when it comes to the AWI and my history tests were a number of decades ago, so some things are bound to get cross wired along the way.

It is not often that I play 20mm to 28mm skirmish games. I prefer to come up a level or two where it is the actions of teams rather than individuals. If you like I wish to know that the house had been taken rather than how it was taken. Having said this if I were looking at a raid then I am interested in how the house was taken or lost, so I am happy to reach for some skirmish rules. Given this I mostly play WW2 using FoW for the battles and Battlegroup for small encounters and raids. I like both rules as they do their job well. Recently I have added Combat HQ rules which are for much larger battles where one tank equals a platoon of tanks with the focus being on the challengers of command and control.

I am attracted to the ACW as it opens with Napoleonics and closes with warnings of WW1. That’s a lot of bang for your buck. I have chosen the regimental rules of Across a Deadly Field at 15mm scale as both are readily available where I live. Eventually this will lead to two armies at about 1000 models. It is a long term project but will start rolling dice as soon as both sides have two regiments of infantry, one of cavalry and a battery of cannon each. I will be turning the painting level down quite a bit, otherwise the project will never be finished. Besides there is a special quality about quantity.

It is too easy today to want to start a new army every day in a different period as just about all points of history now has wonderful figurines and you are spoiled with great rules. The problem is that armies are very expensive in time and money to build. Hence the need of each choice giving you that band for your buck. I see that the AWI does offer this for that time period. The armies involved are not as large as their counterpart wars in Europe yet offers raids, gorilla warfare and battles of the line. Your table can be forests rough hills to gentle farmland. Particularly for the U.S. player you can start with raw recruits and finish with veterans. There is a lot of scope here and you don’t need several full armies to do it. Yet for WW2 your need a minimum of early, mid and late war armies with perhaps a desert or eastern front armies to cover the whole war.

I see this as an issue for younger plays in that if they start too big in a period with lots of diversity such as WW2, by the time they have them painted up they could find that their friends have move on to something else. I also believe there is too much passive pressure to paint up armies to a studio standard. So I think it would be better for them to pick armies that give them plenty of scope and as you say start it small but expand if their group holds their interest for a while. I think half an army could also be good for groups starting out. That will mean a minimum of two people a side, but they get a larger army on the table quicker.

I am interested on your thoughts about this.

For me answer to that is that for almost every game I play I collect at least two sides. This goes back to the long haul build i mentioned earlier. Now I’m not saying it’s a requirement but it makes finding a game infinitely easier and if your group switches rules chances are you won’t have to rebase since everything’s the same.

Building an army with a friend is also a great way to keep everyone excited in the project and on the right track. Communities like this one are perfect for doing that.

Playing with your finished minis is especially important to the younger guys getting into the hobby (I’m 21 and I’ve been doing this for about a decade now) and I think the new 2 Player starter sets do this extremely well. Quick, easy and you don’t have to run around looking for minis. I’ve demonstrated the Perry ACW starter at a local Geek Convention and it works great, there’s also no reason it couldn’t be used for any other period just maybe shorten the ranges.

@elessar I am totally with what you say about. I wargaming now for the better part of 4 decades now and have gamed with the same group for over two decades. Only 3 of us remain from when we started but our group normally is around 8 to 15 people all bringing their favorite games with them so most of us have quite a few armies, range from fantasy to sci-fi to historic (mostly 20th century). When we start something new we choose our favorite army and once it is built up to play a small game we start painting up a second army. Although there is no group rule for it we start with an infantry formation first. For my WW2 Finnish Army I started with 3 platoons of infantry in 15mm painted in such a way that they suit all 3 wars fought by the Finns during WW2. Then I started adding assets to this core for the 3 different wars. Today I can play all three wars in either infantry or tank formations. If someone wants to try something new or different they tend to be supported and encouraged by the group. We tend to play our games at a size where you will get 3 games in a normal 10 to 12 hour session. We also use a handicap system so if you keep winning against a person we increase the size of their army until win vs loss is about 50/50 so that everyone gets a challenging game that tends to be very exciting for everyone. People can organise amongst themselves for larger games and at least twice a year we combine our armies for a game that will need all of us to play. We happily allow people to borrow armies or units on the night, they only have to organise for it. This means you get to play against your own armies. We have found this very educational as everyone one plays an army differently making these games insightful. We also use the historical games to learn and study history. We will decide what elements or aspect we wish to explore. In these games you don’t win in the normal way. You win by how historically accurate you play and we swap sides a lot during these investigations. You could say we roleplay these games.

I like the starter parks and the army lists to start you off. I have played quite a few games just using these and I have demonstrated that these lists and armies are just as good as any other army. I think these get blamed for the underlying fact is that the players are normally just learning the rules and are making beginner mistakes.

Hey, @jamesevans140 – if ACW is your thing, have you seen @elessar2590 ‘s new article series on Sharpe’s Practice (first part on an ACW engagement)?

@oriskany even in my family those that fought from WW1 until today are remembered and at least the key points of their story. Including those serving in East Timor today. Yet the family history goes get and fuzzy for the Boer War and then it goes blank if you go back any further. I know that a branch of my family moved to the U.S. in the early 1800’s but I have no idea to where our if they served in the civil war.

By no means do I think we should not nameplate our regiments and battalions, just not in the traditional way of permanently placing them on the bases of the figurines and models. I wish to wargame any time our place in the civil war. So I will be making a lot of movement trays and nameplating them instead. This way I gain more utility from my greys and blues. Both sides used sharp shooter regiments with many in green uniforms, then you have the various Zouave units on both sides and civilians with guns. So these units will have to be modeled separately. Then you have the greys that have blue uniforms but I will just use standard blues for them.

No I have not seen @elessar2590‘s but I will check it out as I am more than interested. 🙂

By no means do I think we should not nameplate our regiments and battalions, just not in the traditional way of permanently placing them on the bases of the figurines and models.

Gotcha. I’ve never seen that. People actually do that? Man, that’s dedication. 😀

One of the things you need to understand about the American Revolution was the relationship between Congress, Washington and the various states in regards to the army. One thing Congress kept doing, to the annoyance of Washington, was to hand out Generals commissions to the woefully unqualified. Sometimes it was political, sometimes Congress was just duped by flashy salesmanship.

This made truly accomplished generals, like Arnold, extremely unhappy. Washington was also pretty unhappy about it to but mostly kept it to himself.

Great post, @blipvertus – this was definitely the case with Horatio Gates – a darling of Congress. Of course, Gates hated and disrespected Washington, perhaps even more than Charles Lee did. So Washington had to deal with Congress filling many of the Army’s most important positions with die-hard personal enemies.

Of course, not that Gates’ predecessor Schuyler was that much better, but still …

And of course, Gates would “get his” at Camden.

So with Gates “disqualified” by his later defeats and Arnold “disqualified” by his later treason, a lot of the “populist” credit for Saratoga goes back to Schuyler, almost by default. Probably why a lot of what used to be the actual town of Saratoga now stands in modern Schuylerville. 😀

The type of nameplating I am talking about dates back as far as the first 25mm Napoleonic wargames and on the other side of the pond the hardcore Civil War gamers followed suit. To the descendants of these groups even what I suggest here is outright heresy as they nameplated down to regiment level but typical gamed the one battle, like Waterloo, Gettysburg and the like. An alternate developed of nameplating the command group of the regiment.

For me I will be wargaming the Civil War in the same fashion as we game WW2. This style of gaming has been introduced by the advent of 28mm rules but it is still a bit too Nuevo to the traditional large army small scale (LASS, hah a new acronym!) such as 25mm or 15mm. Even the two army list books for Across a Deadly Field are by battle and regiment. There are no ish lists. While we are happy to game an encounter between two historically accurate forces some where during the battle of the Bulge. It is not a historic encounter and so this match would not be acceptable to the traditionalist Napoleonic or Civil War gamers.

If I was to follow tradition I would not be able to game the Civil War without a ridiculous amount of figurines to do it properly.

During the Civil War congress reminds me of some periods of ancient Rome when generalship was handed out to their current pinup boy of the moment. All too often ending in disaster when the pinup boy takes the field.

I must admit I’ve never seen it done either even for command groups. Yes people use real life commanders in their games and their perceived attributes when it comes to C&C etc but I personally wouldn’t go as far as starting to name Lieutenants,Majors etc

I must admit, @jamesevans140 – I’ve nver seen “permanent” name plating of units (if I understand you right) outside of a museum, and then of course it’s a diorama rather than a gaming table.

That would indeed be seriously hard core. Gettysburg at the regimental level is (very roughly) 10 corps (both sides) x 3 divisions x 3 brigades x 5 regiments = 450 units, plus artillery batteries, command, and support units (let’s call it 800 to be safe). 800 units times I would guess at least 4 of 5 figures per unit / base = 4000 figures you could use for exactly ONE battle?

Don’t get me wrong, I name plate constantly, as we see in Parts 04 and 05 of Saratoga. It’s just not permanent and not stuck on the actual unit itself. ;D Hell, I even name plate hex and counter games, as we’ve seen in WWDDC, Four Levels of Wargaming, etc. (although in those cases, perhaps “name tag” would be a better word).

@torros – I’ll agree I don’t nameplate> commanders as the scale at which I enjoy playing is usually too large to accommodate them. We identify them sometimes for rules purposes, but there aren’t usually enough of them to require printed nameplates.

At least in my case, the exception would be these AWI games, where a general can command as few as 1000 men (brigade, depending on the battlefield conditions – and we’re playing at a 1-10 , 1-20, or 1-80 men per stand “command tactical” ratio). This is only because Battlesystem his rules for command diameter, how many units a given officer can have “in command” and as we see with guys like Morgan, Arnold, and Fraser, a +1 or +2 for things like initiative, morale checks, rallies, etc.

So sometimes we gotta keep track, but not enough to usually require nameplates. 😀

Sorry guys a few non days there.

It looks like we have different exposure to this @torros and @oriskany.

From what I have seen the stand of the regimental leaders has the rear half painted white with the regiments name written on it. As many civil war regiments tend to have long names what is written on the base tends to be highly abbreviated. This is a waste of time as far as I am concerned. If you only wargame one or two battles from the Civil War this is fine.

I on the other hand wish to explore the entire Civil War from start to end but maybe not in chronological order, like we do in BG or FoW. I will be looking at brigade level games that are resolved by regiments. In a similar fashion to say FoW is a game of platoons resolved by fire teams.

I like the way you placed name tags against your units @oriskany. So what I am thinking now is gluing magnetic strips to the movement trays. We get a lot of advertising that includes fridge magnets. So I will cut them into strips paint and repainting them with the unit name.

But this is a background project. At the moment I painting up a platoon of the new FoW shift plastic 8th Army figurines. Not impressed over all. If you hand paint on the primer it has a tenancy to pool, spraying works fine. However removing molding seams tends to be a nightmare. While scraping and filing works ok they both tend to leave very tiny dust like balls that are still attached.

But if you don’t try you will never know I guess. So if I were to build an army with these I would not bother removing the molding seams as the first figurine took nearly an hour to clean up.

Thanks very much, @jamesevans140 – glad to see you’re feeling better.