The Sands Of El Alamein: Gearing Up For The FoW Boot Camp [Part Three]

February 27, 2017 by crew

Through the late summer and fall of 1942, opposing armies have gathered near a remote Egyptian railroad town called El Alamein. For months, they’ve built toward a showdown of mortal inevitability. Now the air lays quiet, as if even the desert knows a historic clash is in the making. When it hits, the war in the desert will never be the same.

Greetings, Beasts of War, and welcome back to our pre-boot camp article series on Battles of El Alamein. In less than week, a platoon of die-hard backstagers will gather at BoW Studios to be among the first to play Flames of War 4th Edition, in games that will bring the Battles of El Alamein to the 15mm table top as never before.

In Part One we traced (in broad strokes) the paths taken by the opponents of this matchup (Panzerarmee Afrika and the British Eight Army) that have brought them to this fateful bottleneck in the desert. Part Two has compared the armies, commanders, and weapons of both sides, sizing them up for the confrontation to come.

Setting The Stage

May-July 1942

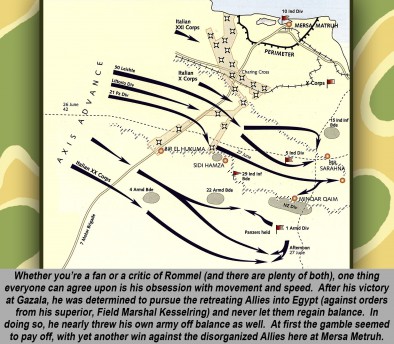

As we saw in Part One, the story of El Alamein begins a few months earlier, with probably the most dazzling victory by General Erwin Rommel (the famed “Desert Fox”). With his Gazala Offensive in May and June 1942, he throws the Allies out of Libya, takes the port of Tobruk, and hurls the Eight Army in chaotic retreat deep into Egypt.

After mounting a disastrous stand as Mersa Metruh, the Allies are thrown back again, this time all the way to El Alamein (just sixty miles from Alexandria). Here, however, the desert becomes quite narrow, thanks to a bend in the coast and a vast dry salt bed called the Qattara Depression. In short, El Alamein is a great defensive position.

His spearheads trying to consolidate in headlong advance, Rommel gathers part of his force and hits the “Alamein Line” in early July, 1942. This time, however, the Allies are ready for him. South Africans, New Zealanders, and Indians slam the Afrika Korps and other Axis units to a resolute, bloody halt. The stalemate of El Alamein has begun.

Alam Halfa

August-September 1942

The British commander of the Eighth Army, General Claude Auchinleck, hits Rommel’s German and Italian forces in turn with several resolute but piecemeal counterattacks through the middle of July. Soon he is replaced, however, by General Harold Alexander and a new commander for the Eighth Army: Bernard Law Montgomery.

Montgomery is determined on two important things. First, restore the cohesion and fighting confidence of the Eighth Army. Second, NOT to repeat the same mistake previous British commanders have made in the desert by hitting Rommel too soon, which has only left the British open to flanking counterattacks and further defeat.

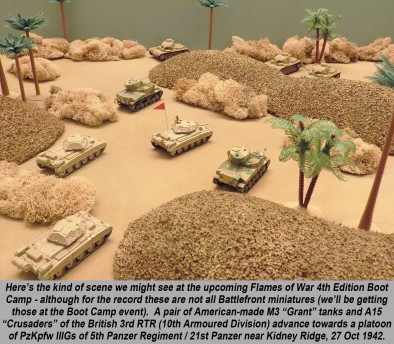

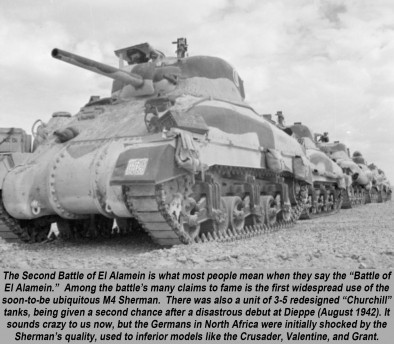

Rather, “Monty” just starts building up. New divisions of tanks, including new American lend-lease models like the Grant and soon the Sherman. New artillery vehicles like the M7 “Priest.” More artillery, more infantry, more air power, and hundreds of thousands of mines.

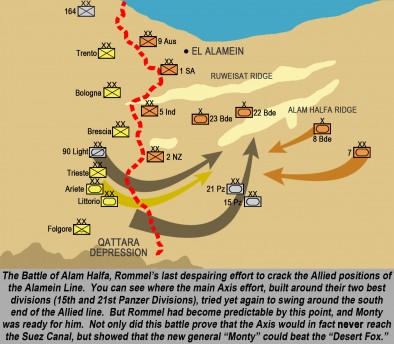

Monty’s patience finally pays off at the end of August, 1942. Starving for fuel, reinforcements, supplies, and above all, water...Rommel desperately attacks the southern shoulder of Monty’s line. Caving in the Allied position and plowing through a deadly minefield, the Afrika Korps turns north behind the Allied line. Has Rommel done it again?

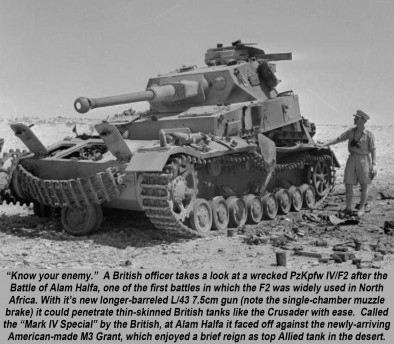

No, he hasn’t. This “turning the southern flank” play has been used once too often, and Monty has seen it coming. In front of the German advance stands Alam Halfa Ridge, where the spearheads of German “Mark IV Special” tanks are engaged by new battalions of M3 “Grant” Lend-Lease tanks.

Long story short, Rommel’s offensive is pinned down and torn apart in front of Alam Halfa Ridge. Monty has proven himself with his first victory, and what’s left of the Afrika Korps falls back to defensive positions. The Germans will never take the general offensive in Egypt again. But of course Monty now has to throw the Axis OUT of Egypt …

Operation Lightfoot

October 1942

After slamming Rommel to a halt at Alam Halfa, Alexander and Montgomery spend the rest of September and most of October getting ready for an offensive of their own. They are determined to make this assault a decisive one, throwing the Axis not only out of Egypt, but hopefully out of North Africa altogether.

Of course building up for such an massive effort will take time, and there are plenty of Allied leaders who feel Monty and Alexander are taking too long. Some of these people are quite influential, including a famous statesman with a rabid appetite for cigars, fine brandy...and firing British generals with whom he has lost patience.

However, the “chokepoint” nature of the El Alamein battle space that made it such a great defensive position for the Allies, now works in favour of Rommel. Critically short on fuel, Rommel is forced to adopt a predominantly static defence, including hundreds of thousands of mines. These minefields will prove a critical factor in the battle.

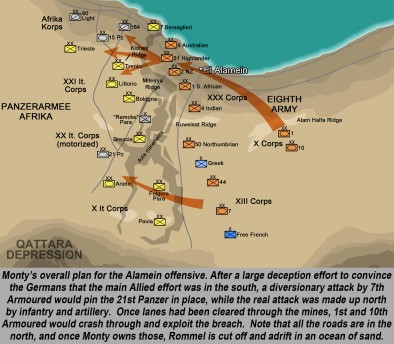

Montgomery finally launches his offensive at 21:40 hours on October 23th, 1943...with a huge artillery barrage that some say was the biggest since 1918. After hitting the Axis rear echelon, these guns start a “marching barrage” through the German and Italian minefields, behind which the Allied infantry and engineers begin to advance.

This is “Operation Lightfoot,” which makes good progress through the Axis minefields for the first half of the night. The attacks starts to bog down, however. By dawn on October 24th, the British are trying to get tanks through the lanes cleared in the minefields, but more mines and German antitank guns are causing massive damage and delays.

By now it’s clear that the main Allied attack is hitting in the north. Despite the divisionary attack by the 7th Armoured, Rommel is able to transfer the 21st Panzer northward to help stabilize the situation. Losses are terrible and the very last of Rommel’s reserves are committed, but Operation Lightfoot is ground to a halt by October 27th.

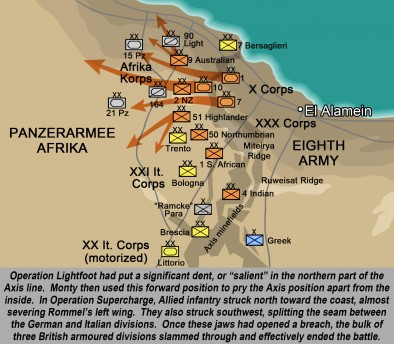

Operation Supercharge

November 1942

Nevertheless, Rommel is in serious trouble. Through the battles of late October, he’s been forced time and time and time again to draw more strength from the southern part of his line to meet the threat in the north. The southern line is now a brittle shell, held by immobile, overstretched Italian units and handfuls of German paratroopers.

Even in the north, the “prime” German divisions of the DAK are in dire straits. Fuel is basically gone, robbing the panzers of their precious mobility. But where previous British generals have paused at such junctures, Monty is already prepared to hit the Axis again.

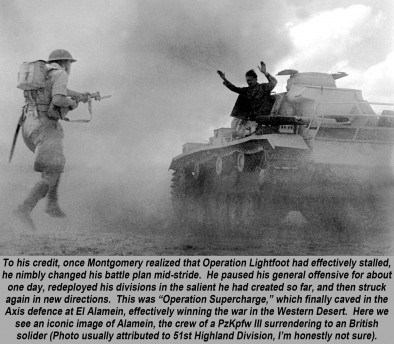

This second offensive is called Operation Supercharge, beginning the very next day (October 28th). Using the salient of ground gained by Operation Lightfoot as a springboard, Allied divisions strike in new, diverging directions. Like a crowbar jammed into a cracked wall, they use this leverage to pry apart the northern shoulder of the Axis line.

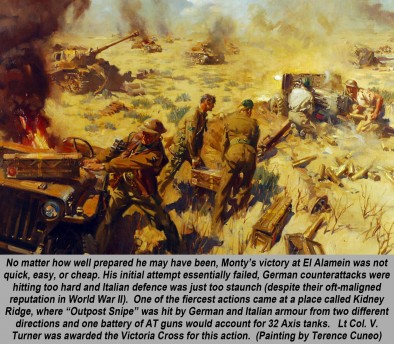

Then, on November 2nd, Supercharge goes into overdrive. After carefully reorganising his divisions, Monty throws the mother of all left jabs not at the Germans, but at the junction of their line with the Italians. Yet even now there is no immediate breakthrough. Italian infantry fight too hard, local German counterattacks are coming too fast.

Numbers, however, ultimately tip the scale. Not just men, tanks, and guns … but fuel, ammunition, food, water. Allied units can just keep fighting, replenished with new ammunition, fuel, and men – while the Afrika Korps is soon down to just thirty running tanks.

On November 4th, Ritter von Thoma, commander of the Afrika Korps, is captured in a battle that sees the veteran remnants of 15th Panzer Division all but annihilated. Later that day, Rommel knows the situation was hopeless, and orders a general withdrawal. The retreat will not stop until he reaches Tunisia, almost 1,200 miles to the west.

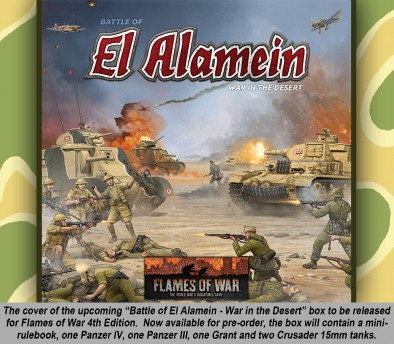

Flames Of War

El Alamein In 15mm

I’ve had the privilege of reviewing some advance materials for Flames of War 4th Edition, and I’ve been looking for rules and considerations included in the game that point specifically to factors in El Alamein. Put another way, how does Flames of War 4th Edition stack up against the history of El Alamein?

Within the constraints imposed on any tabletop miniature wargame, I’d say Flames of War 4th Edition does pretty well at capturing some of the key features of El Alamein. One early highlight for me when in the Desert Terrain page, which begins with: “The terrain of North Africa is far from the flat and empty wastes of popular imagination.”

I couldn’t possibly agree more. Flames of War 4th Edition includes rules for ridges, hills, escarpments, wadis (dry riverbeds), dune hills, rocky hills … all were parts of the El Alamein battlefield. Places like Kidney Ridge, Alam Halfa, Ruweisat Ridge, Dier el Shein, Miteiriya Ridge, Hill 129, Outpost Snipe, all soaked the pages of history in blood.

Rules for “Short Cover” may also help ambitious players simulate the desert tank tactic of “hull down shielding.” This is where a tank positions itself just behind even the smallest fold in an otherwise flat desert, using the dune as a ramp to present only part of the turret and depressed gun barrel for a target.

Flames of War 4th Edition also seems to do a great job with both providing a framework for the approximation of historically accurate units, while allowing players the freedom to play with the units the like and the minis they have on hand.

One example I found straight away is including both the Crusader II and III. The Crusader II had a 2-pound gun and a three-man turret. The Crusader III squeezed in a bigger 6-pound gun but only fit two men in the turret. Thus the unit card gives the Crusader III a bigger, longer-reaching gun (with the same ROF) but the “Overworked” special rule.

Small examples like this show that the writers of 4th Edition have done a great job with providing just enough historical detail to make “real tactics” work on the table. This encourages players to use and research historical solutions to challenges in the game, all without bogging down play with too much “rivet counting” detail.

I, for one, can’t wait to try out my “Deutsches Afrikakorps” units on a live table at the boot camp!

I’d like to take this opportunity to “tank” everyone who helped with this series, including my editor @brennon and @lancorz for the amazing work on front page and banner graphics – as well as @warzan and the team at large for letting me publish on Beasts of War.

Most of all, however, thanks to all of you for taking some time to read these articles, and even better, drop a comment below. Does the “desert wind call to you?” Will you be trying out the new 4th Edition Flames of War starter kits, taking on the role of a “Desert Rat” or one of Rommel’s grizzled “Afrika Korps” veterans?

By the time you read this, we’ll be counting down the last days before the BoW Flames of War 4th Edition Boot Camp. I hope to see many of you there, and if you aren’t able to join us in person, PLEASE check out and participate in live blogs being run all weekend. If previous boot camps are any indication, this weekend will be amazing!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"The Germans will never take the general offensive in Egypt again. But of course Monty now has to throw the Axis OUT of Egypt..."

"Within the constraints imposed on any table top miniature wargame, I’d say Flames of War 4th Edition does pretty well at capturing some of the key features of El Alamein..."

![10mm Medieval Miniatures! Azincourt English Army Review | Wargames Atlantic [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-azincourt-english-army-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![Mounted US Cavalry On Kickstarter For Dead Man’s Hand! [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/us-cavalry-main-600-338.jpg)

![Play WW2 Commando Operations With Butcher & Bolt [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/relaunch-600-338.jpg)

thank you for a great article 🙂

I have always looked at the battles of El Alamein as something the British would always win. Given the advantages they have in numbers an supplies. Well prepared positions and no room for Rommel to do his usual flanking manuvers.

Wish I was going to the bootcamp, but will have to be an armchair general at home 🙂

@reiton – thanks for the post. 😀 I pretty much agree with what you say re: the foregone conclusion on El Alamein. The one exception being if Rommel had won decisively (again) at First El Alamein (early July, 1942). The Alamein line hadn’t really solidified in place yet, Auchinleck was still trying to reassemble some of his units from the Gazala / Mersa Metruh retreat, etc.

If he’d won another big one there, and captured yet more stockpiles of supplies (half the reason he launched many of his attacks, simply to steal British supplies since he was always so short on his own), he just might have made it out of the Alamein-Qattara bottleneck and gotten to Alexandria.

Once at Alexandria (a major port), he’s got all kinds of supplies. There are also no further good defensive positions (where the desert gets very narrow). Alexandria would be denied as a port from bringing in Allied supplies and reinforcements, and Rommel is again free to use his wide-ranging flanking attacks with which he’s had such success (he’s got the space and the fuel to do it).

Definitely a very narrow “window of possibility” here, and once we get to later engagements like Alam Halfa, yeah, I don’t think the Germans have much of a chance. Even if the Axis had managed to hold the line against Lightfoot and Supercharge, The Anglo-American invasions over in West Africa make Rommel’s position in Egypt untenable anyway.

Long story short, it’s late ’42. The Axis is really running out of possibilities by this point. 😀

Even with a win at El Alamein, and new supplies he would still need new tanks, and I guess more importantly fresh troops. Unless he got a win that wiped out most of the 8th army. I seem to remember reading somewhere that Hitler promised all kinds of reinforcements to DAK that never arrived.

So many ifs, that again its the ifs that makes all of this fun 🙂

If the 8th army got back to Alexandria somewhat intact I guess it would be as hard to take as Tobruk had been. But if worked, DAK got reinforced and could push on into.. not Israel yet 😛 and threaten the oilfields in the middle east… would have been a longer war from there.

But same conclusion, I dont see anything changing that Germany was running low on manpower at this point.

I have to agree with just about everything in your post, @reiton – Like I was saying with @warzan in another thread, I don’t think the middle east oil fields were never really in anything resembling danger, if they were, they’d be threatened by Kleist’s Army Group A from the Caucasus at this juncture of the war (summer – early fall 1942).

I don’t want to “spoil” anything for the boot camp, but honestly I think Rommel lost the Battle of El Alamein the second the first tank crossed into Egypt after the victory at Gazala. Now if he had kicked the British out of Libya and stopped at the border, I know what everyone would be writing in today’s history books – “oh, what would have happened if only Rommel had pursued the Allies into Egypt . . .”

He was ordered by his superior (Kesselring) to stay put. But instead he hurled his army into Egypt and into a situation where there really was no way correct answer leading to victory, or even survival.

If he’d stayed put, Auchinleck may never have been replaced by Alexander / Monty, Rommel wouldn’t have lost most of 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions at Alam Halfa, and his supply lines back to Benghazi would have been much shorter.

I think Rommel still would have lost … eventually (numbers just keep stacking up) … but definitely would have lasted a lot longer in a campaign of maneuver at the open Egyptian frontier (as opposed to a frontal slugging match in the Alamein bottleneck against such huge numbers).

How much longer, I don’t know. And is that really relevant, in light of what was happening in Northwest Africa vis-a-vis Operation Torch? Open for conjecture, I suppose. 😀

Reading your reply gets me thinking that the only way the axis would ever have won in Africa the Italians should have been able to do it on their own.

I belive they had the numbers to do so, But useless leadership that eroded the soldiers morale.

If Italy could have taken Malta early on, then maybe they could have given England more competition for control of the mediterranean. its a fun thought experiment 🙂 I will show up for the bootcamp when we play that battle 🙂

Indeed, Operation “Hercules” (proposed invasion of Malta) would have made a very big difference had it been carried off in late 41 / early 42. But honestly, this was a war the Italians never should have started. The British were more concerned at the time about the Balkans (as demonstrated by the hobbling of Operation Compass when the Germans went into Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete in the spring of 41), and were content, at the time, to leave the Italians in Libya be.

Sure, there was fighting in East Africa (again, instigated by the Italians – another war they weren’t that prepared for), but North Africa was a campaign that probably never should have started (at least from an Axis geostrategic perspective).

Great final article @oriskany from what I have been reading Monty basically had a three stage battle plan “Getting-in” the “Dog-Fight” then “Getting out” and he was under no illusions as to how brutal the “dog-fight” would be he told his men it would be hard and bloody and could take a dozen days and so it proved.

Absolutely, @commodorerob – I can’t remember Monty’s exact phrase, but it was something like “this is going to be a ‘killing’ battle,” of some such.

With the flanks closed off by the sea and the Qattara Depression, some variation of a frontal attack was really the only option to either side. Monty did have a diversionary “army” in the south of radio traffic and dummy units (almost like a mini D-Day “Operation Downfall”) to try and divert German strength and reserves away from his planned northern attack corridor. Then, for Operation Lightfoot 7th Armoured attacked with 44th Infantry and other units to add to this deception, and try and pin 21st Panzer in the south.

It didn’t really work, the massed artillery barrages up north where Allied infantry and engineers were cutting lanes through the minefields (28 feet across and sometimes 5 miles deep, I think) tipped Rommel off where the real attack was coming.

Anyway, getting through these minefields was the “getting in” part you mention. Once lanes had been cut through the minefields, tanks of 1st and 10th Armoured went through to engage the main German / Italian line of resistance, fight off the inevitable counterattack, and force Rommel to commit the balance of his reserves. This is the “dogfight” portion you mention.

Finally, the breakout into the open desert beyond, or “getting out.”

It . . . largely worked, jut not perfectly. Lightfoot largely stalled after a couple of days, but without missing a beat Monty redeployed 7th Armoured up north, and re-shuffled his infantry units in the “Kidney Ridge Salient,” and struck in a new direction from that salient won in Lightfoot. This, of course, was Supercharge. So Monty sort of had to do the “Dogfight” phase twice . . . but it paid off in the end and be got the break through November 4-5. 😀

Yes Killing Battle that was the words I was tying to recall. It is very much this operation/s that Monty was given all his praise for and why he was loved so much. He may not have been the best commander in the war (certainly better than a certain American General .. 😉 ) But the fact that he not only stood his ground against the politicians an refused to fight until he was sure that his forces were ready, he also was regularly seen by his troops and many of them had never seen their generals before, he inspired them. and he also had the intelligence to understand that “that no battle plan withstands contact with the enemy” to quote a well know German General, so he adapted and did not panic.

Great reply, @commodorerob –

It is very much this operation/s that Monty was given all his praise for and why he was loved so much.

Absolutely. The only argument I was trying to make in previous articles in this series was the credit that is also deserved by some of his unjustly forgotten predecessors, especially Auchinleck (okay, only Auchinleck) who fought some of the initial El Alamein battles that stopped Rommel (First Alamein and Ruweisat Ridge), who saw the potential of the El Alamein battlefield as a last-ditch defensive line, who had preparations there underway as a contingency before they were even needed, and who set up the initial field works, minefields, and units there to hold Rommel until Monty took over for the Battles of Alam Halfa Ridge and Second Alamein.

He may not have been the best commander in the war (certainly better than a certain American General .. 😉 )

You’ll get no argument from me there. Actually, I don’t know if I would put one above the other, both were solid, but both also had big flaws and certainly not God’s gift to generals.

But the fact that he not only stood his ground against the politicians an refused to fight until he was sure that his forces were ready

Absolutely. This was huge. Again, I would shine a little of the spotlight on Harold Alexander, Monty’s immediate superior and thus standing between Churchill and Monty . . . But yes, this was mostly Monty.

He also was regularly seen by his troops and many of them had never seen their generals before, he inspired them.

Absolutely true. After all these defeats and retreats, after winning ground only to give it up because of vacillating leadership of meddling politicians with priorities on other fronts, Monty said “We are going to fight here. We are going to stay here. And if we cannot stay here alive, then let us stay here dead.” It sounds grim, but this is what the troops needed to hear after six generals had come and gone in command of the 8th Army / XIII Corps / WDF.

Great final read @oriskany, I have a quite unique momento of the desert campaign which due to its size I won’t be bringing to the bootcamp. As I previously mentioned, my grandfather was a gunner/driver in a 25 pdr crew and he brought back some shell cases one of which he turned into a fire poker stand. It’s dated 1942 on the base and I reckon they must have got through a fair amount of them. I’ll take a few photos so you can see it alongside the other items I’m bringing.

Thanks, @brucelea . Yeah, I can only imagine how many 25-lbr casings were piled up through the course of El Alamein. Almost 1,000 guns, firing for hours at a time, day after day. I’m surprised they weren’t building little “igloo shell casing houses” out of them. 😀

Definitely looking forward to seeing all this stuff. As for me, I’m making the last pieces for the campaign map, the map itself, packing some extra units, books, magazines, etc.

Ohhh, and let me offer an “errata” retraction before anyone pings me on this . . .

In the article, when the battle begins, the text reads: “Montgomery finally launches his offensive at 21:40 hours on October 23th, 1943.” Yeah, clearly that’s supposed to read “1942.” A simply typo.

G**damnit. 🙁 I research the hour and minute of the attack, and then get the friggin’ YEAR wrong.

Apologies. 😀

@oriskany Another great article! By far your best of 2018!

Okay, @koraski , I guess I had that coming. 😀

I can only answer with this . . .

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ytCEuuW2_A

😀 😀 😀

a great finally to the article @oriskany hope you and the other players have a great weekend killing tanks.

Thanks, @zorg ! Glad you liked the article and hope you like the live blog coverage! 😀

its going to be great are you n john going head to head on a game? @oriskany

P. S. don’t forget warm cloth its still chanking cold here.

I don’t know about playing John in a game, @zorg . I wold like to play John, Justin, or both. But they might be busy running the event. Hell, I’LL be busy with the campaign event. Maybe in the Free Gaming afterwards. Also, I;ll be in Coleraine a few days after the event, I think Warren wants to do some more filming.

yay the more the merrier guys loving all the videos.

Great read again, I envy you that go to the bootcamp

Thanks very much, @rasmus . So now we’ve seen how it took place historically. Here’s hoping me fellow DAK players and I can change things a little! 😀

@oriskany I would have said if WW2 had kicked off in 1936 their armoured would be dominated Europe. I do think they were ahead if everyone else. Whether they could have developed better stuff as the war went on like other countries did during the war is a different matter

I am referring to Italy here of course

It’s definitely possible they would have done better, @torros with an earlier start of WW2. I’ve read the same for the Czechs and the Poles. (Strategy & Tactics Magazine had a “Rhineland” issue a while back postulating if Germany’s occupation triggered an early start to WW2 in 1936 – complete with mail order wargames). With Germany only three years into its 1933-39 buildup, and Britain and France scarcely having begun theirs, it would have been tough.

It bears noting, though, that while nations like Italy somewhat might have been a place of relative strength (compared to some of her neighbors at that moment), i think you’re right, their industrial, training, and logistical base wouldn’t have kept pace for very long.

Having an army that is marginally “less weak” compared to others at a particular point in time is one thing. Building an long-lasting army with strategic depth is another. Complete with an competent officer corps staffed by solid men (not appointed for religious, family, or political ties) and a deep, long-lasting infrastructure for expansion, maintenance, and expeditionary deployment (which is what the Italians were all about, fighting if far flung places).

I mean the M11/39 and M13/40 were okay for 1936. By 1940 they were deathtraps.

@oriskany I don’t think Italy set up a tank school until 42 or 43

Far too late by then. 🙂

A nice finish to the series and lead-in for boot camp @oriskany.

Alamein 2 shows Montgomery at his best and media wise his most annoying. He demonstrates that he will not follow a plan to its logical failure but will switch to another plan. Yet when questioned by media about the failure he replies what failure, there was no failure everything turned out as planned. He certainly did his best to remove the great work of Auchinleck and claim it for himself and he certainly would not share any of it with Alexander, his boss. It shows a very nasty side to his character.

By this stage of the war there is nothing Rommel could have done to win in the desert. To the British this is the main event but to the Germans this is a side show and their main event, Russia, was consuming the German war machine faster than it can be replenished. The Afrika campaign has died on the vine. With Operation Torch even the vine dies back a long way.

This is not helped by the fact that the average Italian has no interest at all in building Rome mark three. When comparing Italian forces fighting in Russia to those in Africa they are two extremely different militaries. If the Italian heart had been in it like it was in Russia there would have no need for German intervention.

Yet the German loss at Alamein 1&2 will be Rommel’s own making that starts with the failure of not taking Malta and will finish in Tunisia. No one in the German high command well work with Rommel due to the abuse and disrespect that Rommel had given them. His disdain for the Italians also adds to his defeat. At every opportunity he belittled them so there was no chance he could of inspired them to fight like they did in Russia.

There is a plan that works for the Germans at Alamein 2 but Hitler would not have approved it and is not in Rommel’s nature. Don’t fight it.

It also relies on one more partial top up from Germany to work as well.

A fighting withdrawal from the Alamein position as Monty is expecting, with more resistance in the north so Monty will transfer units from the south. About halfway between Alamein and Tobruk go on the offensive with a usual swing from the south. Yes Monty may have expected it but on such an open flank doing something about it is another thing especially when if the resistance in the north had done its job units would have been stripped from this flank. Now it is a matter of swinging north and cutting the 8th Army off from its supply lines. Old habits should kick in as the Veterans of the 8th Army know what happens if they don’t retreat. The aim is to occupy the old positions held by the 8th Army at Alamein and keep the 8th Army on the retreat forcing them through these positions. Then it is time for the Germans to stop at these positions and consolidate. Another thing Rommel was not good at.

My logic behind this is that if you have the smaller force you should never engage in positional warfare as you can’t win the attritional stage. Therefore you must draw him out so he can be engaged in maneuver warfare where you do have a chance at winning. Rommel was a tank man and you have to keep the tanks rolling. Even this would only amount to a last victory. Getting the amount of supply and reinforcement to advance further into Egypt is highly doubtful and Operation Torch will finish it even it the supplies did get through. The taking of the Suez was never going to happen and it was Auchinleck’s victory that closed this door. No matter how I have looked at the second battle of El Alamein it is just the swan song of German efforts in Africa.

As I can’t attend the boot camp I hope that all who do have a truly great time of it.

Alamein 2 shows Montgomery at his best and media wise his most annoying. He demonstrates that he will not follow a plan to its logical failure but will switch to another plan. Yet when questioned by media about the failure he replies what failure, there was no failure everything turned out as planned.

Oh my God, this is so true! And something I have never understood about Monty or Monty fans. At Second Alamein he shows a great degree of tactical deftness and operational flexibility. Lightfoot FAILS (there, I said it), but Monty doesn’t lose a day, reorganizing, reshuffling, and pivoting “Supercharge” in a new direction. The plan is different enough to keep PanzerArmee Afrika off balance but still uses the salient of ground gained in Lightfoot as a springboard so those men didn’t die for nothing (actually important for morale, I think).

Yet Monty and many Monty fans won’t “take credit” for this, instead insisting that this was the plan all along.

This exact same thing happened in Normandy on a much larger scale. The AMERICANS were supposed to pin down the Germans while the British made the breakout toward Paris. That’s WHY THE BRITISH WERE LANDED SO MUCH CLOSER to Paris and the Channel ports. Instead the opposite happened, and at least a lot of it was under Monty’s command (Bradley’s 12th Army Group was JUST being activated, until then he commanded only 1st Army under, you guessed it, Monty’s 21st Army Group). But Monty’s hubris never lets him take credit for shifting his balance like this, it’s always “all part of my bloody strategy, ole’ chap!”

Any boxer is only as good as his footwork, and Monty had great footwork. But he’d rather us remember him just standing in the ring motionless trading punches. I don’t get it.

Completely agree about the impossibility of Rommel’s situation by this point, like I was saying to @reiton above.

The Italians . . . man, one of these days I feel like I should write a whole series just about them. Few armies in WW2 are as misunderstood, including by the Italian leadership at the time as well. The summer of 1940 saw the French collapsed and the British collapsing. Mussolini, who had never thought that much of Hitler and hitherto wanted nothing to do with a continental WW2, suddenly realized Germany was about to run away with everything. The Fall of France, for example, technically gave Hitler half of Africa.

Mussolini wanted the other half. He KNEW his army wasn’t ready. It wasn’t ready because they didn’t want this war, weren’t ready for this war, and hadn’t spent the last 6-10 years building up for this war. He assured his generals they wouldn’t HAVE to be ready, they were just going to run around and scoop up some undefended or weakly-defended territories. Hitler had chopped down the tree, Mussolini just wanted to snatch up some fallen fruit.

And he wasn’t even expecting to win, really. A direct quote: “All I need is to suffer a few thousand dead and I can sit at the peace table as a man who has fought.” I think he was picturing more a limited war and wanted a seat at the next Versailles. Given the accolades given him at Munich, I can see why.

And of course Italian success (yes, Italian SUCCESS) in East Africa against the British there seemed to justify this “strategy” (if you really want to call it that).

But then of course the British didn’t cave in Egypt. Nor did they cave in the Battle of Britain and of course Germany never invaded. Italy suddenly had a real fight on their hands they were absolutely NOT prepared for.

Then Hitler came down and saved him in Greece. And Yugoslavia. And Africa. Then Hitler called in his favors, and the Italian Army was sent to its death. Not in North Africa, not in Italy . . .

In Russia.

Excellent stuff. Ready to get my “hull down” on at the bootcamp. Great work @oriskany

Thanks very much, @gambit505! 🙂

@oriskany Enjoyed the read on all the articles.

In response to you and @commodeorerob and your discussion:

“rob – But the fact that he not only stood his ground against the politicians an refused to fight until he was sure that his forces were ready

oriskany – Absolutely. This was huge. Again, I would shine a little of the spotlight on Harold Alexander, Monty’s immediate superior and thus standing between Churchill and Monty . . . But yes, this was mostly Monty.”

The issue with this is that it led to Montgomery’s drive later to always have overwhelming superiority in future operations before he would take action due to his desire to not fail. While this can be a good trait, it also brings risk as you forfeit a lot of the initiative to the enemy.

But as Peter Geyl said in “Napoleon: For and Against” – History is an argument without end 😉

Thanks very much, @mwcannon – I would have to agree that Monty’s reliance on “crumbling” tactics and application of overwhelming force in a given area really slowed him down in Sicily and again in Normandy. He caught a lot of grief for it, too. To the the point where the normally very conservative, very cautious, very over-prepared Montgomery launched Operation Market-Garden, one of the riskiest and least-prepared gambles of the war. 🙂

This is why i put Monty and Patton in the same bag @oriskany.

While it can be rightly argued that they are completely different personalities and are different people brought up in completely different circumstances. They’re product of their actions remain the same. On the battlefield they can be brilliant and dexterous. Yet they could both be very flat footed. Away from the battlefield they could leave almost as much damage in their wake as they leave on the actual battlefield. It is this that makes them two peas in a pod.

Monty is also odd like Oliver Cromwell in that they both cycle through periods of public like and dislike. At the moment Monty is going through a revival period yet years ago in my history class I was taught he was a second rate general that made many mistakes and failed to take Caen in time and cost the unnecessary loss of Canadian and British life. Finally being bailed out by US efforts. Today it is taught that he struggled to take Caen but had intentionally drawn off the German armour and reserves to allow a clean breakout from the U.S. flank.

The facts remain that a number of battles were fought around Caen and was not taken on D-Day. The Germans assumed that Caen was the centre of gravity and arranged their forces in accordance to their assumption. The U.S. forces broke out of their beachhead. So you can interpret the general facts anyway you like. However given the dismay by the U.S. generals at Monty’s failure in accordance to the invasion plan. So if it was Monty’s intention to draw off the German units he failed to convey this to the Americans. Given that he had command of all allied ground forces at the time he may have believed he did not have to.

The Italian army of this period is a very complex and contradictory force. If you do write a series on them you should start with their conquest of Italian east Africa, then the Spanish Civil war, east Africa against the British, the Western Desert and finally their outstanding success in Russia and their decline in Russia, Sicily and their surrender.

While they had no say on who their political master was, they seemed to vote with their fighting ability on policy if the general soldier agreed or disagreed with the policy in question. The general soldiers certainly had no issues in shooting any officer that tried to force them to enact a policy they disagreed with. A very complicated lot.