The Sands Of El Alamein: Gearing Up For The FoW Boot Camp [Part Two]

February 20, 2017 by crew

A frigid, dry cold numbs the desert’s predawn blackness. There is no frost, the air is too dry. Even before the sun breaks the horizon, the empty wind is challenged by the diesel cough of engines. Here and there, the snap-hiss of a signal flare, the distant squawk of a radio.

The dawning glow floods into full daylight, the black desert sands spreading with yellows, browns, and whites, all reaching westward. Now the armies can see each other...sort of. The last night patrols are in, and from somewhere in the wind echo the first snaps of machine gun fire. A new day has come to the Desert War.

Welcome back, Beasts of War, to the second instalment on our El Alamein mini-series. Our aim is to sketch in some context and background for the games of Flames of War 4th Edition we’ll be playing all too soon at the Beasts of War Boot Camp. And for those who are attending, and participating in the live blog, we hope to crank up the excitement!

In our Part One, we outlined in the broadest of terms what the Desert War was all about – how and why it started what both sides were trying to achieve, and the battles that led to the stalemate at El Alamein. But stalemates never last, and in July of 1942 the Desert War was about to shift in a radically new direction.

Assemble The Ranks

Comparing The Armies

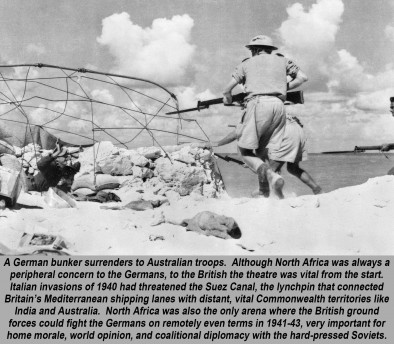

So let’s compare the armies of the two sides. On the Allied side, we have the Eight Army, a multinational Commonwealth force under British command. In addition to British soldiers, we have Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians, and Free French, along with a host of smaller contingents from other nations.

The Eighth Army enjoyed a significant edge in numbers, equipment, and supply. After all, the advantage to having your back to the wall is your supply lines are very short. Many of these men were also desert veterans, having served in the desert since the days of Operation Compass in 1940.

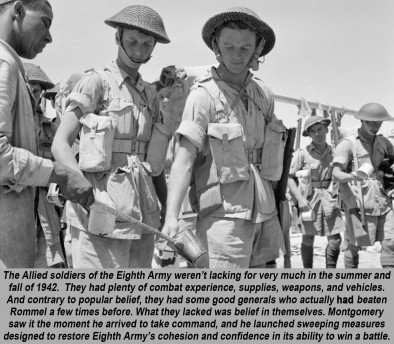

However, the Eighth Army also suffered from a lack of confidence. They’d been defeated so many times. Even when they’d won, their victories had been squandered by sometimes ineffective generals and meddling politicians.

They’d honestly come to regard their enemies, especially Rommel, as an almost mythical (and invincible) figure.

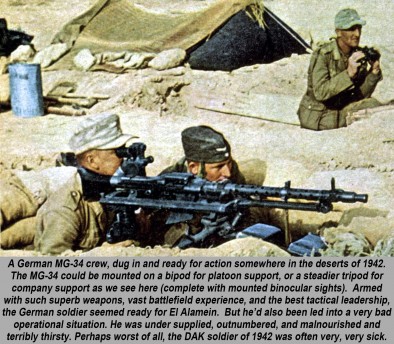

In contrast, the Germans at El Alamein can almost be considered a “photo negative” of the Eighth Army. “Panzerarmee Afrika” as it was now known, was tough, aggressive, confident both in themselves and in their leadership, and convinced that North Africa (and World War II overall) was a conflict that could still be won.

However, the condition of their supplies, equipment, and vehicles turned out to be appalling. Although Rommel had taken the port of Tobruk, many of its port facilities had been blown up so most German supplies had to come all the way from Benghazi or Tripoli … IF they even made it past British air and sub bases on Malta.

German tanks and artillery weren’t the only things breaking down through lack of supply. The men were facing a critical health problem mostly through lack of water. Without water for hygiene, diseases like jaundice and dysentery were causing major problems. Rommel himself was very ill for most of 1942 with these tropical ailments.

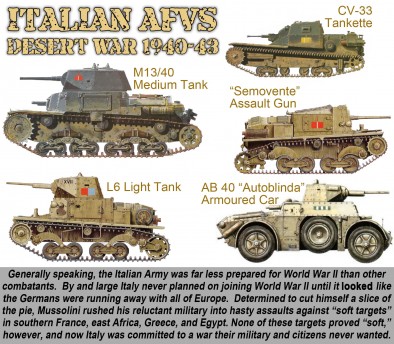

Also, whereas the British of Eighth Army could rely confidently on their Australian, Kiwi, South African, and Indian allies, the Germans held no such confidence with their Italian comrades. Italians made up a huge portion of Panzerarmee Afrika, including two of Rommel’s four panzer divisions.

This isn’t to say that Italian troops or divisions were universally “terrible.” Once under competent leadership, and given the confidence that comes with winning a few battles, they repeatedly showed they could fight very hard. This was especially in prepared defensive positions since Italian units had very few trucks and were very immobile.

Still, the inferiority of Italian equipment (tanks, antitank guns, artillery, support vehicles etc.), and more importantly their almost complete lack of mobility made them a dangerous weakness in Rommel’s order of battle. They best they could really do was dig in and if the Allies hit them, hold on as best they could.

At The Generals’ Table

Comparing The Commanders

Part of what makes the Desert War so prevalent in the popular memory, and the Battles of El Alamein in particular, is the “cast of characters” we see among the generals. First of these, of course, is Rommel. The figure of the “Desert Fox” and his famous sand goggles is practically inseparable from the Desert War.

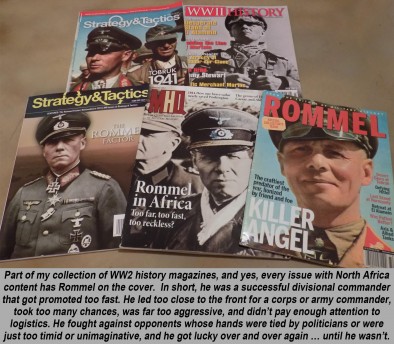

But was Rommel really as great as the movies say? Honestly, no. He was an exceptional divisional commander in the French Campaign of 1940, yet he led too close to the front, took too many risks, didn’t take orders, and refused to coordinate with other divisions in his corps. In short, he wasn’t a team player, and war is a “team sport.”

Yet he was undeniably successful. Between February 1941 and June 1942, he was promoted to lead a corps (the Afrika Korps), then Panzergruppe Afrika, and finally Panzerarmee Afrika. That’s too many promotions in too short a time, and while no one can doubt Rommel’s tactical talent, his operational and strategic vision remains suspect.

Others have noted Rommel’s complete disconnect with the logistical side of war, leading his army deep into Egypt with supply lines 1,000 miles long and constantly under attack. And finally, his higher-level plans weren’t very imaginative, he just kept turning the southern “desert” flank of successive Allied armies.

Now at El Alamein, he could no longer do that. Still, he tried a modified version of this same “schtick,” with a hook southward at First Alamein (July 1st to 3rd, 1942), and again at Alam Halfa Ridge. But by now he’d become completely predictable, and both Auchinleck and later Montgomery were more than ready for him.

So yes, Rommel was one of the best division commanders of World War II. But when it comes to commanding a corps, army and later army group, he becomes one of the worst. Just ask German military historians. When they’re asked to list the top five German commanders of World War II, Rommel’s name never comes up.

Which brings us to the British . . .

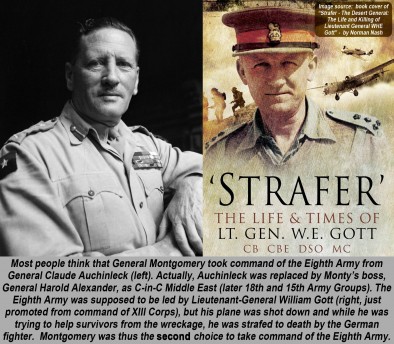

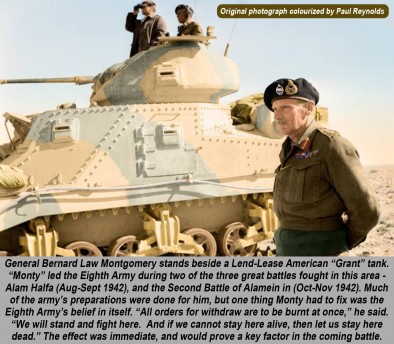

Bernard Law Montgomery’s victory at El Alamein was so famous he would be named “1st Viscount of Alamein.” Of course, he has plenty of detractors, particularly among American historians. I won’t add to the list, but I’d like to point out that a lot of credit for El Alamein should go to one of his predecessors, Claude Auchinleck.

It was Auchinleck to first saw the potential for El Alamein as a defensive position to stop Rommel. Auchinleck had beaten Rommel during operation Crusader and again at First Alamein in July 1942. Auchinleck had built most of the fortifications and minefields that would give Monty the time he needed to prepare his Second Battle of El Alamein.

Still, Monty still deserves loads of credit for rebuilding 8th Army’s confidence in itself. He also steadfastly resisted pressure from Churchill to launch an offensive until he’d first built up a sizable reserve corps AND broken Rommel’s last attack at Alam Halfa. Churchill’s meddling had brought the downfall of many prior desert commanders.

Arms & Armour

Comparing The Weapons

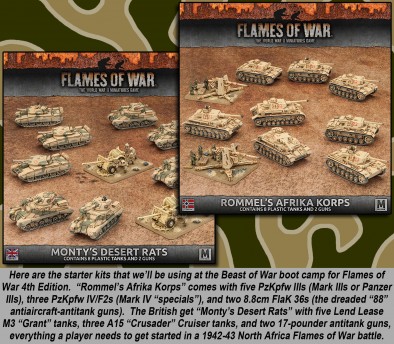

Now it’s time to get down to nuts and bolts...literally. Let’s compare the tanks and artillery on both sides, especially the tanks and artillery we’ll be getting in our Flames of War 4th Edition starter sets (Rommel’s Afrika Korps and Monty’s Desert Rats).

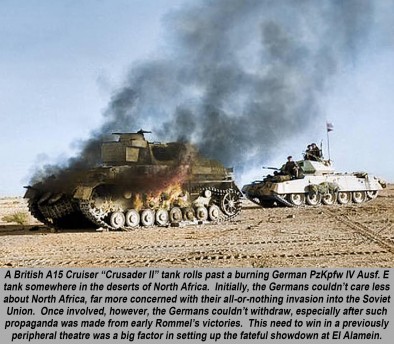

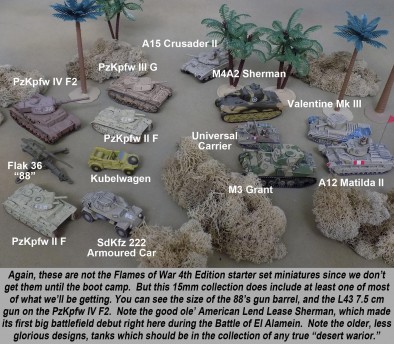

For the British, the first tank in the set is the Crusader, or specifically the “A15 Cruiser Tank Mk VI.” Used by the British almost from the start of the war, it endures as one of the iconic symbols of the North Africa Campaign. It was fast, especially over rough ground thanks to its Christie suspension, and hard-hitting with its 2-pounder (40mm) gun.

However, the tank was plagued by a catalogue of mechanical problems. It truly seemed “designed to fail” especially in a desert environment. Also, the 40mm gun could not fire HE ammunition, making it useless against soft targets. And finally, that 40mm gun was rapidly outclassed by bigger German guns and better armour.

Eventually, the 40mm weapon was replaced by a 57mm, 6-pounder gun. But to install it, designers had to take out the dedicated gunner crewman. Now the commander had to fire the gun, degrading crew efficiency. Eventually, replaced by the American M3 Stuart light tank, the Crusader’s career died in the desert.

The British also get the American-made M3 “Grant” medium tank. At a time when British tanks didn’t’ have sizable guns for HE work, the appearance of the Grant’s 75mm dual-purpose gun was more than welcome, even if it was mounted in a rather silly-looking sponson on the right side of the tank.

The Grant’s big weaknesses were its multiple gun mounts and turrets (never a good idea), and its towering height. While it makes for an imposing miniature you don’t want to be this tall on a real battlefield. Desert tank tactics like “hull down” shielding were next to useless with the Grant, and it would eventually be replaced by the Sherman.

On the German side, we have the PzKpfw III (Panzerkampfwagen, or armoured fighting vehicle). Originally armed with a 37mm gun, these upgrades were mounted with 50mm guns. The “G” variant carried an L42 version of the 50mm (KwK 38), the “J” variant (Mark III “Special” by the British) carried a longer L60 version (KwK 39).

Longer gun barrels mean higher muzzle velocity, range, accuracy, and kinetic armour-piercing power. As they lengthened the guns on their Mark IIIs, the Germans did even more so with their Mark IVs, as we see with the PzKpfw IV “F2” and “G” variants we see in the starter kit.

Originally armed with a very short (L24), low-velocity 75mm howitzer, these newer Mark IVs were armed with L43 KwK 40 75mm. This was a dedicated anti-tank gun with a high muzzle velocity and solid armour-piercing killing power, yet could still fire HE shells for engaging trucks, bunkers, artillery, or infantry positions.

Still, both the Mark III and IV had problems common with many German vehicles. While the Germans were masters of upgrading and repurposing vehicles, the fact remains that these were OLD vehicles. Maintenance and parts were always a problem, and although up-armoured, these tanks had trouble when larger Allied guns began to appear.

Finally, we have the artillery. Originally an antiaircraft gun, the FlaK 36 “88” is a legend in its own right. The British 17-pounder would become almost as famous, and while not yet in service at El Alamein, would appear on the battlefield during the battles for Tunisia in early 1943.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our second look into the Desert War and the Battles of Alamein. The ramp-up to the Flames of War 4th Edition Boot Camp is counting down fast, so get your comments in below and tell us what you think of what’s been presented so far. I hope to see you all at the boot camp or the live blog coverage!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"...whereas the British of Eighth Army could rely confidently on their Australian, Kiwi, South African, and Indian allies, the Germans held no such confidence with their Italian comrades"

"Let’s compare the tanks and artillery on both sides, especially the tanks and artillery we’ll be getting in our Flames of War 4th Edition starter sets..."

![Perfect Call Of Duty-Style Miniatures? Wargames Atlantic’s Operators Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-operators-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![Zenit Miniatures’ Samurai Warlords Now Live On Kickstarter [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/samurai-warlords-launch-main-600-338.jpg)

Great history, @oriskany ! You’ve encapsulated the background, the personalities, and the vehicles, in a fast entertaining read. Monty wasn’t popular with us either, as our boys always felt he would ‘fight to the last Canadian’ in later campaigns in northwest Europe. 🙂

Thanks for kicking off the comment thread, @cpauls1 – and I hope you saw one the M3 Grants you sent me to the right in Image 10. 😀

As an American, I’ve certainly been “raised” on a habit of looking down at Montgomery. Some of it is certainly justified, but a lot of it objectively isn’t. Battles are won or lost before they’re fought, in World War II, telephones, shovels, and clipboards counted a lot more than artillery or tanks. This was something Monty always understood, and I give him all the credit in the world for not letting himself be pushed into premature attack as so many of his predecessors in the desert had been.

All that said, Monty traditionally gets all the credit for the victories at El Alamein. The British even made him “Vicount of Alamein,” etc. Not to take anything away from Monty, but there are plenty of others who deserve a big piece of the credit, especially his unofficial predecessor Auchinleck (who actually won the First Battle of El Alamein, as reviewed in Part 01). So no, it wasn’t Monty who “proved” Rommel could be beaten. Auchinleck had already done it . . . twice (adding Operation Crusader to the list).

Certainly would agree with the “fight to the last Canadian” idea. I know a big part of 21st Army Group comprised of 1st Canadian Army (at one point up to half 21st Army Group). From Juno Beach to the Channel ports to II Canadian Corps at Scheldt Estruary, Canadians often seemed to be at the heart of the worst battles.

Thanks again! 😀

A quote from “Monty”Python seems suitable here.

“Oh, get on with it!”

😛

Great post, I wasn’t yet aware of the fact that Monty’s predecessor had died shortly before his nomination.

“Get on with it?” Patience, grasshopper. 😀 Remember what Sun Tzu wrote:

Military discipline means organization, chain of command, and logistics.

Strategic Assessments

Those who face the unprepared with preparedness are victorious.

Planning a Siege

Therefore the victories of good warriors are not noted for cleverness or bravery. Their victories are not flukes because they position themselves such that they cannot lose, prevailing over those who have already lost.

Formations

In other words, battles are won or lost long before they are ever fought. El Alamein was a stellar example of this, and why I wanted to go into a lot of detail on the build-up for battle.

Anyway, the First Battle of El Alamein (the one that really stopped Rommel) was already fought, and discussed in Part One. In Part Three we go over Alam Halfa and the final collision of Second Alamein (along with some observations from looking through advanced copies of 4th Edition FoW).

Then again, if your impatience is just to get to the Boot Camp, get together with some great gamers, get some awesome tanks, and start chuckin’ dice, then yes, I agree. 😀

LET’S GET ON WITH IT! 😀

LOVE the vivid imagery!!!

“The dawning glow floods into full daylight, the black desert sands spreading with yellows, browns, and whites, all reaching westward. Now the armies can see each other…sort of. The last night patrols are in, and from somewhere in the wind echo the first snaps of machine gun fire. A new day has come to the Desert War.”

I think when I’m done reading this series I might actually be able to follow what is happening on the tables at the boot camp 😉

Thanks very much, @gladesrunner – As far as “following what happens,” I’m sure a lot of the battles will be just starter kit armies lining up and shooting the crap out of each other. This is especially true since most of Second El Alamein was artillery and infantry, and we’ll have tanks and antitank guns. But we just wanted to sketch out the contextual basics of what happened, which might lead to some scenario-driven play later in the weekend. Who knows?

@oriskany great article!

Is a desert theatre (on balance) a bigger challenge for armies or just a different challenge?

I would imagine if it were not for the oil fields it’s the last place you would want to fight?

I would say the 2 biggest problems are firstly the sand. Machinery and sand don’t mix,from memory both sides had a lot of break downs and other mechanical failures during the campaign

Secondly to my mind is the other logistical problem is having to transport water etc every where you with few local sources,and being the desert you need more of it than usual. I would guess both sides had to keep a constant supply coming across the Med to supply them though the British holding Egypt might have been in a slightly better position

Thanks, @warzan . 😀

On balance, I would say a different challenge. I presume we’re talking “desert operations” in general, as opposed to the specific Desert War in WW2, or El Alamein in particular (where oil wasn’t a factor). While the desert presents a great number of additional obstacles for a mechanized army to face, it also removes some obstacles armies may face in other environments.

In fact, many British and German officers were actually looking forward at first to see what the mechanized divisions could really do without all this rubbish in the way. You know, rivers, canals, trees, towns, people . . .

The desert presents a stack of additional problems, as @torros mentions. I would add to the ones he mentions – the extreme variance in daily temperatures (depending on which desert you’re in). Deserts are famously extremely hot in the daytime but terribly cold at night. This expanding and contracting of metals, rubber, seals, hoses, belts, can really do a number of vehicles and equipment, especially in WW2, when chemical engineering wasn’t what it is today

In a less technical sense, the desert also removes a lot small-scale tactical problems and wider-scale operational obstacles.

1) Everyone in the military hates mud. Not much mud in most deserts (Tunisia in December of 1942 being a notable exception.

2) The worst battlefields on earth, bar none and full stop, are cities. These are the “last places you would want to fight,” trust me. And there aren’t that many big “urban battles” in the desert (Bagdad, Basra, and the Sunni Triangle in Iraq 2003-2011 again being the notable exception).

3) Not many roads. While this can be a problem for the attacker, it can be a boon to the defender since it makes enemy movements predictable.

4) Not many civilians or refugees in the crossfire. This frees up “big boom” support assets like artillery and air strikes.

5) Movement or visibility is not usually a problem the way it is in, oh, say . . . Vietnam.

6) Oil fields were not really a factor in the WW2 desert battles, but Saddam Hussein infamously blew up a lot of oil fields in his retreat in from Kuwait and southern Iraq in late February – early March 1991 during Gulf One. I think this was more of a vindictive act of vengeful destruction than any kind of tactical ploy, since it didn’t slow anyone down during the closing stages of the war. Of course it caused tremendous economic and environmental damage (including mankind’s first small-scale, short term, and regional-scale “nuclear winter” as temperatures in the Middle East were measurably dropped as if after a large volcanic eruption).

So yes. Deserts of course present a portfolio of obstacles that are easy to identify. But they also remove many obstacles armies face in other environments. In summary, a “different” challenge.

What sometimes makes deserts SEEM to be a “worse” challenge historically is that armies are better prepared for other areas, and that makes the desert a much more cruel mistress. 😀

@torros – I would agree with your two “problems” of desert warfare, adding on the additional perspective that the two sides didn’t suffer from both problems in equal measure.

The sand hurt the British a lot more than the Germans, I think. Especially in regards to tanks, especially in regards to the woeful little A15 Crusader. As David Fletcher from Bovington Tank Museum says: “The Crusader was never a good tank, but what flaws it had, the desert exacerbated them to a disastrous degree.” Not only are the air filters not desert-equipped, but they’re placed at the ear of the tank along either side of the hull, EXACTLY where the most dust and sand is going to be kicked up by any tank at speed (speed being the Crusader’s one saving grace). The fans aren’t driven by belts, but by chains. So they can’t really expand and shrink with the wild temperature variations, etc.

Anyway, just one example. German vehicles were fitted with better tropical and desert filters, coolants, lubricants etc., to better keep them going.

The British didn’t really come out of this problem until they started receiving American equipment. Not that American tanks like the Grant, Stuart, and Sherman were fitted with special desert filters, but they were built by US car manufacturers and . . . oh yeah, we HAVE big deserts in our country, as well as frozen sub-arctic forests, plains, mountains, sub-tropical forest-jungles, swamps, etc. Many American vehicles were just naturally built to handle different climates, and so lasted better in North Africa. The British loved the Stuart so much they re-named it “Honey.” Not because it was some awesome attack vehicle or war-winning weapons platform, but it friggin’ started when you hit the start button and kept going until you got where you were going.

As for your other point on Logistics – I couldn’t agree more. I’ve compared the North African campaign to two boxers trying to win a bout with bungee cords tied around their waists, constantly tugging them back to their own corner. The further your advance and harder your beat your opponent into his corner, the harder your own supply line is trying to pull you back into your corner. This is a big part of why the two armies swept back and forth over Cyrenaica and the Sidi Barrani-Mersa Murtuh stretch of Egypt time and time and time again.

Here, I again agree, the Germans suffered worse than the British. The Germans could never coax Spain into the war, which would have sealed Gibraltar, and they could never get the Italians and their airborne divisions to help in Operation Hercules, the planned invasion of Malta. So the Royal Navy was always able to stay on top of the Italian fleet (which was actually very solid, until setbacks like the Battle of Matapan and of course the “British Pearl Harbor” raid at Taranto).

Anyway, British naval supremacy in the Mediterranean (for which they paid a very heavy price, two examples: HMS Barham and the Pedestal Convoy) meant that the Axis were always on the wrong end of the supply and logistics imbalance. Water, as you mention, is a real crusher. Water goes to drink, and whatever is left over goes into vehicles. Which leaves nothing for bathing or hygiene. This would prove a massive factor at El Alamein, where most of Rommel’s men were sick with dysentery, jaundice, or other diseases.

Rommel himself, as you probably know, wasn’t even in-theater for the start of Second Alamein in October, 1942. Back home in Germany for medical treatment, trying to beat these same hygiene-related tropical diseases.

what about the infamous ‘desert mirage’ and navigation in what effectively is a featureless and constantly shifting environment ?

Did that make the few roads even more important ?

Or did they simply navigate by the stars in this pre-GPS era ?

Good call on the navigation and GPS angles, @limburger . That’s very true. Those points were addressed a few hours ago about 9 posts down in a reply to @torros . 😀 (these posts are going up in a crazy order). 😀

On point 3, my unit’s main task in the 1st gulf war was to build 2 main supply routes for 7 armd bde for all of the reasons mentioned previously. No supplies, no capability! Plus new roads aren’t on any map and therefore can’t be interdicted by artillery (as they had no air power).

“No supplies, no capability!” – I did time both as an MOS: 3043 / Supply Admininitration and Logistics and as an MS: 3051 / Supply and Warehouseman – so I approve of this message! 😀

Oh yes, the Iraqi Air Force. Who can forget their “Battle of Britain” moment when Gulf One started? Fly en masse to the Iran, land, and ask “can we spend the rest of the war here?” Never mind that Iran was their mortal enemy all through the previous decade.

7th Armoured Brigade – that’s the “descended” unit from 7th Armoured Division, The Desert Rats we’ll have at the Boot Camp! 😀

I am going to dig out my old jerboa badge and bring it along. I was only issued one and it went missing in camp 4 (Saudi Arabia) but a good mate of mine acquired me another

Awesome. Like the “rat” insignia I found on this restored Bren carrier on a recent trip to Normandy . . . (in a parking lot just overlooking Vierville Draw – Dog Green – Omaha Beach).

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/desert-war-additional-photos-maps-discussion?topic_page=2&num=15#post-131545

Weird, half my post went missing

The other bit is that I’m going to bring along some stuff of my grandads that I think will interest you @oriskany, as he was a gunner/ driver in 8th Army.

Awesome. Can’t wait! 😀

a great read @oriskany as all ways preparation, preparation, preparation, and quotes from Sun Tzu as well.

Thanks very much, @zorg . It’s a tough thing to do in wargames. Ina wargame, both players get an army, you battle it out, and knowledge of the rules, imaginative tactics, and a little help from that sexiest of all women, Lady Luck, delivers victory to one side or the other. The point is, the outcome is decided on the table.

Historically, this is never the case, especially at the very, very, very small scales typically represented on wargaming tables. So when designing a historical “scenario-based” game (as opposed to tournament lists or the like), we always have to strike a balance between “historical realism” (where really one side or the other has already won) and keeping the game fair and fun for both players. 😀

Asymmetrical victory conditions are my favorite way, but don’t respond well to “points” or other conventions, and can only be hammered out and polished to perfection through playtesting.

its that or rack your brain to make a handicap system to level out the points.

Certainly possible. I tend to prefer scenario-driven objectives and modifiers, with the units on the table determined only what was actually present historically, but that’s just me. Say the historical winner, on the attack, managed a big breakthrough. Well on the table he’ll greatly overpower the defender, but if the defender can kill x-number of attacking units (more than were lost historically) or can delay the attacker’s advance past a certain amount of time, or force the attacker to take a longer route, or whatever, then the defender wins even as his army is wiped off the table.

Losing the battle, winning the game.

plus extra units for winning side for next battle.?

Okay, @zorg , now you might be talking about some kind of campaign set up, where the winner of a game gets some kind of edge in the next game in a series? Definitely fun, had some success with those. The factor to keep an eye on in such a set-up a “campaign momentum.” If one side wins a few games early on they can quickly built up enough of an advantage or lead that the other side can never really catch up.

This certainly happens in real warfare. But not always such a good idea in a wargame. Don’t get me wrong, you can manage it. It’s just something to keep an eye on, especially early on i the series/

wasn’t thinking that way more each battle say a heavy weapon team or a tank extra for the winning side but no additional units as you say to much of an advantage would make the win to easy after several battle wins.

Okay, @zorg – I think I got it. So by “winning side” you mean the historically dominant side. Well, in a “historical scenario” model – they probably already have extra units based on the research that shows / proves units that were actually on the field you’re talking about.

If you’re just trying to “approximate” a historical precondition, I don’t know if I would add heavier units, just more of them, to simulate a greater force density at the attacker’s point of impact.

You can also work with reserves, objectives, and deployment areas (as we’ve seen in many FoW games). Say you’re trying to work something up for Operation Lightfoot at the beginning of Second El Alamein (23Oct42) . . .

Okay, the spearhead of the 1st Armoured Division is trying to get through a lane cut through German minefields the previous night by 9th Australian Division. You’ve got some Allied infantry staged halfway up the table (9th Australian forward line). Some British tanks coming up from the back of the table, through very tight, narrow, and clearly-marked gaps in a German minefield. If the British deviate, they are destroyed /immobilized in the minefield.

Also, the die rolls they have to make to bring up reserve units (more tanks) is very tough since these mine lanes are long, thin, susceptible to traffic jams, and under German off-board artillery fire.

Furthermore, their tanks HAVE to approach only along very avenues of approach where the Germans (164th Division and 15th Panzer Division) can easily set up 88s and 75s.

Finally, the British have to cross the whole table, get “X” number of armoured units off the German edge of the table as breakthrough units, can only suffer “Y” number of casualties, and must accomplish all this is “Z” number of turns.

Sound unfair? Not really, since they outnumber the Germans 10-1.

THAT’S historical wargaming.

Points and army lists are for tournaments or casual play, IMHO. 😀

I get you.

🙂

Great read, the narrative at the start has really gotten me excited for the bootcamp!

Thanks, @gambit505 – Indeed the boot camp is gonna be awesome!

Nice reply James. Thank you . The logistics part of the game is one of the reasons I am looking goward to Sam Mustafa’s new WW2 game

Thanks and no worries, @torros . – “Logistics is the ball and chain of armored warfare,” as Guderian wrote. Always true, of course, but especially more so in the desert. It’ll be interesting to see how the new game handles this. World War 2.5 had a simple resource / activation mechanic at the divisional level (as many other games have done in the past) but of course that wasn’t in a desert environment.

Another thing I meant to mention about difficulty in desert operations was navigation. Simply getting large numbers of men and vehicles to all move the right way without getting lost (in an operational scale, of course) is really hard.

Or hell, even in a tactical sense, I’ve talked to Marines who were at Desert Storm on patrol, especially at night, in a featureless desert . . . when they stopped for a break someone laid down their rifle pointing which way they’d been going. After the smoke and water break no one would know which way they’d been going (starts aren’t always visible and rocky deserts don’t allow deep tracks).

GPS was originally invented (or at least first deployed) by the US military to allow complex maneuvers in a deep, deep desert previously thought to be impassable. This was half the reason Schwartzkopf’s famous “left hook” worked at all in Gulf One . . . VII and XVIII Corps, and the French units on the far west wing were able to hook right through that empty desert and cut off Republican Guard divisions near the Basra road because Saddam’s generals were convinced that “no large army” could navigate that desert without getting lost.

Great read once again

Thanks very much, @rasmus . I don’t suppose you’re coming to the FoW Boot Camp, are you? I certainly would hope you are, but if you’re not, my tanks probably have a better chance of survival (my poor T-72s are still having nightmares about your Abrams and Cobras). 😀

I’ll have to sit this one out – it is not as easy as it was, to pop over to Colraine

If I were going I would have tried to go German , PzKpfw III and IV for the win

I heard that. I spent all weekend, ALL weekend (and yes, we had a 3-day weekend for Presidents’ Day) getting my PzKpfw IIIs and IVs ready for the boot camp. 😀

The kid had a 3 day weekend, but I had the joy of going to work Monday

Well, I spent the WHOLE DAY cross-eyed with bits of plastic three inches in front of my face, but at least I got some completed minis out of the deal. 😀

Might be good I sit it out if you, @buggeroff and myself that might bring the force out of alignment ; )

Right? You, me, Mick, Andrew, Rob, Dave, Stu, Guillaume, the BoW crew . . . the last time we were together to play Team Yankee, World War III almost broke out for real (with that whole Turkey-Russia shoot down incident).

Yes, as “god-elementals” of wargaming, we need to be careful. With great power comes great responsibility. 😀

my 2 cent… great article Jim, thanks 🙂 can’t wait for the bootcamp, really looking forward to it

Thanks, @buggeroff – It’s definitely gonna be great. And I think we’re on the “same side” this time, right? Are we both playing German / DAK? Or is my brain already been frying in the desert sun too long? 😀

Another fab article, Looking forward to the bootcamp myself will be good to meet up, hobby, roll some dice and share a few beers…

Thanks very much, @cousins286 – one more article to go next Monday, and then . . . well, it’s the boot camp later that same week! 😀

In reference to winning a particular battle and it was me running it I think I would lean towards better resupply and bringing existing units up to strength for he winners while the losers while being allowed to resupply would have less supply points and would be more reliant in bringing in less experienced troops etc over the idea of just giving the winner more stuff

@torros – Okay, so we’re talking about a “campaign series” where each tactical minis game influences the next one? (I’m trying to keep up with a couple of conversations here).

I would 90% agree. At first glance, winning a battle on Monday doesn’t mean extra tanks “magically appear” on Tuesday. What it does do, however, is allow additional fuel, ammo, replacement troops, etc.

But here’s where winning a battle sometimes does cause additional units to “magically” appear. More fuel means more mobile / responsive operational reserves, which means more tanks might be brought up from staging areas in the corps / army rear.

Also (and this was huge in the desert) – winning control of the battlefield at the end of the day meant that your tanks could be towed back to repair depots and a large portion of them brought back into service. Enemy tanks were either blown up or dragged back, often even repaired and used against their former owners (this was more in the earlier part of the Desert War – one whole British BRIGADE (2nd Armoured Brigade, I think) was equipped with Italian M13s when they first encountered Rommel). It was in Part 2 of last year’s Desert War series.

So the winner might have more stuff for a future game in the series, but as a result of the better supply you mention. Otherwise, the campaign needs to have a very solid system for reflecting the effects of supplies and logistics (certainly possible, juts might add a little bookkeeping, unless you’re using something more abstract like a dice roll modifier, etc).

Well due to various work related delays and such like I have only just caught up on this. onc again an excellent article. I am really looking forward to this Bootcamp, a week and a half to go….woohoo.

And some more models turned up yesterday so need to get on and start getting them done:-) all in the name of practicing my paint scheme:-)

If you’re painting British, @commodorerob , then I envy you. 😀 I’m just finishing my German DAK force, and sticking to historical paint schemes (for the Germans it was verrrrrry simple- which actually makes it actually pretty hard to do), it was tough to make it interesting.

British camouflage schemes in the desert were often more complex and interesting.

Thanks very much for the comment and kind words! 😀

Good read again @oriskany . Most of it I kind of already knew, but it is good to get some validation of my “half-knowledge”. If you are about to boast, that Rommel actually wasn’t that great of an army commander, you better be confident about your knowledge.

Btw: What does “schtick” mean? Never heared that before.

Looking forward to the next article and meeting you on the bootcamp.

Thanks, @bothi –

Please understand that when I say Rommel was a poor “army commander,” I mean just that – an “army” commander. Of course he was an excellent divisional commander (blatant insubordination aside – never a good trait in a soldier), and a very good corps commander. But when he was later promoted again and his force expanded into a panzer group and finally a panzer army, his record really starts to falter.

He really only won one real battle as an army commander to my knowledge: Gazala. And even this is highly suspect. While you certainly can’t argue with the results, the razor-thin margin by which he COULD have lost this battle disastrously, and so very nearly did, clearly points to the fact at Rommel got lucky.

In summary, he swung around the south end of the Allied line (gasp, not that same move . . . AGAIN), pushed way too far, way too deep, and rather than cutting off the Allies, damned near got HIMSELF cut off behind their fortified lines. For a few days the two sides were cutting each other off, I’ve compared it to two wrestlers who have each other in a headlock, it’s down to a gut-check to see who passes out first. The fate of the Afrika Korps and Panzerarmee hung by a thread, and Rommel’s men simply toughed it out a little more in a last desperate attack to break BACK toward their own lines (through 150th Brigade Box). But this was just as much to kick out of the trap into which Rommel himself had led them, rather than dealing any calculated death blow to the Eighth Army.

Then you have Mersa Metruh, which almost doesn’t count. A fleeing enemy tries to make a vain stand, and Rommel is already on top of him and smashes the new position before it has a chance to form up.

After that, it’s defeat after defeat. Three defeats in a row at El Alamein. Defeat at the Mareth Line. Defeat at Tebessa Gap. Defeat in Normandy. He never wins another battle.

I don’t really “blame” him for all of this, of course. By 1943 Not many German commanders were winning any battles anywhere. And I think Rommel was just promoted too far, too fast. In 1939 he’s commanding one regiment. By the end of 1942 he’s commanding not just an army, but an army group. That’s the kind of career path generals usually make in 10-20 years. He did it in three. The rules are totally different at these different levels, and frankly I don’t know if it’s reasonable to expect him to have adapted.

At the divisional level, it’s about tactical flexibility, command from the front, and speed. Rommel’s hallmarks.

At higher levels, it’s about detailed preparation, staff work, coordination with other forces in a larger picture, and logistics. Rommel’s many Achilles’ heels.

“Schtick” – eh . . . a trademark, a hallmark, a trope, a gimmick or certain style of performance associated with a specific person. Undertaker had his “Dead Man” entrance, Jimmi Hendrix used a lot of feedback in his electric guitar, Warren used to say “stunning” a lot. Rommel’s “schitck” in North Africa was swing around the south, swing around the south, turn the left flank, turn the left flank. It got very repetitive and starting with First Alamein in July 1942 – fatally predictable. Still Rommel kept it up for Alam Halfa, where Monty was really waiting for him and handed him his head.

Looking forward to seeing you at the boot camp as well! 😀

Good article @oriskany, nice crib on the gear. For once I believe that the comments almost outshine it. This to me is the measure of an article is to promote conversation, so this article is right up there.

One point to remember is that Rommel’s good luck seems to run out with the demise of the German spy ring in Egypt. While Monty arrived in the desert with Ultra and a knowledge of Operation Torch. In War there is no substitute for reading the other guys mail. It also makes measuring these two generals that much harder.

Rommel’s other bad habit was eating the same ration as his men. While this may make for romantic reading he did not understand he was denying the muscle between his ears. Monty does not get enough credit for is his use of crumbling attacks. It might seem overly simple at the tactical level to launch an attack with the sole purpose of destroying a 75mm gun. Operationally this is going to be eventually devastating to a side with supply problems like Rommel.

According to my uncles Monty was a man who would come into a room to inspire you but after a half hour you either felt like shooting him or were praying for a stray enemy shell to put you out of your misery. He really was not a man of the people yet he was one of the very first generals to use the media in an active way to build his reputation.

Setting up victory conditions for a historical wargame whether it is a stand-alone or part of a campaign is never easy. No one way to define a winner either by points, set time limits or conditions seems to work well by themselves. It appears to be the difficulty of squeezing a battle onto a tabletop. At best you are only going to get is a snapshot of a battle from a very limited perspective. The abstraction of time is another issue. Given the distances traveled it would seem like we are only looking at a few minutes of the battle when we are using miniatures representing from a single man to a handful at best. A method that has been evolving in my group is to discuss beforehand what elements of the battle we would like to explore and agree on what units should be there and play a game. Then we discuss any insights we have learned. Then with our knowledge of the battle and what should and now what would happen next we look at our performances and decided a winner. If the people involved are too competitive by nature then perhaps the best approach is a points based game that is handicapped by previous performance of the players involved. I have read in many other forums that younger players believe that it is not a proper test of their generalship if they end up with a smaller force or one that deploys only half its units at first and the rest appears in a staggered fashion in the form of reserves. Yet this is perhaps the most historically correct. Most generals enter battle with far fewer men than they would like. Given how limited our snapshot of a battle is more than likely a draw would be a more normal outcome once you consider the time slice we are using. The Western Desert Campaign brings its own issue in that what is happening at the strategic and operational levels tend to impact more directly on the tactical level. This may be a result of so few units in such a large battle space means there are much less resources or reserves and perhaps how this environment eats away the endurance of the men involved. What happened or did not happen last night more than 100 miles away can decide the outcome of a battle just as much as anything else. Most gamers don’t like the idea of their battle being decided for them. Imagine the fluid turning up in large amounts, but the engines think it is water and the men thinking it’s fuel??

Thanks @jamesevans140, and great post!

For once I believe that the comments almost outshine it.

Indeed the comments have been great. Now if we can just get some of these guys to write some articles . . .

Rommel’s good luck seems to run out with the demise of the German spy ring in Egypt.

Another part of this (I’m embarrassed to say) was because of an American liaison officer. Earlier in the war, when America was not yet in the conflict but supplying Lend-Lease aid, there was an American colonel (his name escapes me) who was sending reports on the desert campaign back to Washington. Well, America wasn’t in the war yet and their intelligence services (disjointed as they were in the pre-CIA days) wasn’t quite on a war footing, and thus not taking wartime precautions. Well, the Germans were hearing every word this guy was beaming back to the War Department, how American equipment was being used, British dispositions battle plans, etc.

Oops. Hey, you guys wanted us in this war, remember?

Rommel’s other bad habit was eating the same ration as his men.

Yeah, the reason Rommel wasn’t in Africa for the onset of Second Alamein was his return to Germany for medical treatment, dysentery and jaundice, the same diseases his men were suffering. Rations combined with hygiene (which would include water rations). So I would add “drinking and washing” with the same ration as his men.

Monty does not get enough credit for is his use of crumbling attacks.

Can’t argue with that, at least at El Alamein. There really are no flanks, the desert is only 45 miles wide or so thanks to a bend in the coast the Qattara Depression. No matter how you cut it, there’s gonna be a frontal attack involved sooner or later, and such “crumbling” tactics are one of the better ways out of a limited situation.

[Monty] was one of the very first generals to use the media in an active way to build his reputation.

Absolutely. All three of the “famous” desert war generals did this, including Rommel first, then Monty, and finally Patton. I would argue that while Rommel was “first,” I think a big part of his media shine was imposed on him by Goebbels and Germany’s media machine. Don’t get me wrong, once it started, Rommel quickly took up the bit and ran with it (one of many reasons he was so haaaaated by fellow German generals). Monty came along and I think did it mostly himself, with his distinctive look and quippy little catch-phrases. Finally came Patton with his absurd pistols and swearing. Sand goggles, beret, and ivory-handled pistols, this seemed a war more of accessories than of armor. 🙁

Setting up victory conditions for a historical wargame whether it is a stand-alone or part of a campaign is never easy.

Indeed it isn’t. It helps when your group is more concerned with historical authenticity than winning and losing (as you say in your post). If you have a game where you play the Soviets in Barbarossa, for example, and you get “realistically slaughtered,” you start to get that visceral feeling of “how did they get through this” and the game can still be interesting on that level. To get historically-asymmetric games to come out balanced and fair requires a lot of playtesting (to the devil with points and army lists!), which in turn requires patient players. 😀

Given how limited our snapshot of a battle is . . . what is happening at the strategic and operational levels tend to impact more directly on the tactical level . . . What happened or did not happen last night more than 100 miles away can decide the outcome of a battle just as much as anything else. Most gamers don’t like the idea of their battle being decided for them.

Yes, yes, and yes. 😀 This is the great (shhhh …) Achilles’ Heel of miniatures gaming, and why it often isn’t the best way to wargame in post-industrial conflicts. Example: I’m watching the VLOG for the tables, and Warren’s talking about terrain. Leaving aside the fun, visual and social aspects of miniature gaming, how would we really handle terrain? Take something like Point 27 or Kidney Ridge. This desert is FLAT, with a terrain feature like Kidney Ridge being one of the whole tables. That whole table is considered 3-4 inches above the other 11 tables in the studio. Whoever controls the Kidney Ridge table, only THAT side can use indirect artillery fire on any of the other tables, where those 10.5 cm or 25-pounder batteries (on this scale) would have ranges across 100-200 feet of miniature table. The battle space would run .4 miles, so from the bridge across the Coleraine River to the Bed & Breakfast hotel where we’ll be staying . . . THAT’S the size and scope across which these battles took place.

Now of course, you can never do that on a minis table, that’s where representational-scale games like 6mm GMT MicroArmor comes in or hexes and counters like Panzer Leader etc. It’s just the kind of thing you have to bear in mind and “abstract your way through” when designing these kinds of scenarios.

The scene Rommel command post in North Africa…..

(German Adjutant rushes into Rommel tent). “Herr Rommel,Herr Rommel The Britishers have broken through our lines”

Herr Rommel “Curses! All our washing in the mud again!”

Hold on, Rommel is actually in his command post? His staff doesn’t have to comb the desert looking for him? 😀 😀 😀

I think that is why they failed to assassinate Rommel as they kept targeting his HQ.

I was aware of the American Colonel you mentioned, however his name escapes me at the moment, but I believe Rommel referred to him as the good source. Wargaming in general begins to have issues with space-time from about the American Civil War when ranges of individual weapons start to open up.

One way of getting over the range issue in many modern games is to use exponential linear measurements where 4″ represents about 100yds while 8″ is about 400yds and 32″ is about a 1.5 miles. The old school method was to use a completely different measurement scale to model and scenery scale. With this method the barrels of a Panther and Firefly could be touching but are supposed to be 500yds apart. The new method at least cuts down on the barrel touching but the downside is that now your regimental artillery is starting to live on the table. I have never tried to calculate what 72″ equates to on the new exponential scale. Given popular wargaming prefers 1 figure represents 1 humanoid and the preferred height of that figure is between 28mm to 32mm. So we are creeping back towards the original 54mm scale. Any one of these scales causes a lot of issues with weapon ranges to the point where all weapons are in range and just the weight of fire counts. Needless to say that any movement is suicide as the term shot really means burst. It would seem we have a triad of movement, distance and range that are 3 different things that seem to be unsolvable on the single tabletop unless you drop to say the 2mm scale.

Good morning, @jamesevans140 –

Okay when I got home I was able to check other writing on this subject. Found in my notes:

If the British had an eye on the Italians, however, the Italians had an eye on the Americans of all people (newly arrived in the war, don’t forget). Italian intelligence had tapped radio communications in the American embassy in Rome, and also the office of the American military attache to the British in Cairo. Here, an officer named Colonel Fellers was doing a very good job at keeping his American superiors current on British forces, plans, supplies, and deployments, using the so-called “Black Code” which the Italians had broken. Rommel called this source of intelligence his “little fellers,” which never let him down until Colonel Fellers was transferred in June 1942.

I recently read the novel “Killing Rommel” by Steven Pressfield. Actually one of my favorite military novelists, in fact probably by TOP favorite, he normally deals with ancient Greece. His one foray into WW2 to my knowledge was the LRDG missions to assassinate Rommel.

I agree completely about the challenge miniature gaming faces when you start getting into more modern times. Once you’re into … say WW1 … it starts to get tough without the kind of representational scales you mentioned. I believe games like GMT Microarmor play representational 6mm but where each piece is a platoon, so the miniatures don’e have to be in scale with the terrain. Given that there are usually 4-5 tanks in a platoon or troop, and the fact that one miniature = a platoon to troop (i.e., 1:4 of 5), allows the normal 6mm scale of 1:256 to be cranked up to about 1:1000 or 1:1200, which I think is what GMT is played at.

For my money, if you’re playing by platoon, I’d just go with Panzer Leader anyway. 🙂

Just to keep the intelligence spillage going an American women working for what will become the OSS has an affair with an Italian naval officer that leads to a booklet being photographed and given to the British that happens to be the Italian naval codes. Neutral or not everyone is in everyone’s pocket which seems to be the Mediterranean way of doing things.

The thing I remember most about Fellers is that he was a very thorough man and the size of his reports were more like volumes. The telephonist must have hated him.

On the gaming side as players we play our own part placing a lot of demands on any rules set. We want multi units on a one to one figure scale, it must be combined arms with air support, if we do an invasion by sea we must bring the ships along and oh it must fit on a 6×4 table. If my kids brought me a demand list like this I would tell them to run not walk.

I am looking at set of rules at the moment that uses 15mm models with a tank or stand of men representing a platoon. It’s primary focus is on command and pushing through the orders. It is a bit on the raw side at the moment and army lists need broadening. It would be for those that already have the models, would like to use them in a new way and is not for the PL types out there. I will try to get Yarrick to give it a go during our Operation Sea Lion games.

Awesome. Well, at least this OSS woman was partially redeeming American intelligence by making up for the damage Fellers had inadvertently caused.

That 15mm “command tactical” (or “scaled tactical”) game sounds great. I would wonder if that would change the scale of the terrain you’re making, or would that really matter? Not for the PL, types, eh? Well, I’m a “PL type” and I have the models. In fact, now that I have enough models (especially non-armor units like infantry and mortars) I’ve always thought about simply running Panzer Leader in miniatures one time, exchanging hexes for inches much the way some players do in BattleTech.

Glad to hear your group is still sticking with the Sea Lion project. Too often projects like that fall by the wayside under the pressures of job, family, etc. As always, please let me know if there’s anything you need (well, after the middle of March, anyway), and I’ll see what I can do. I look forward to seeing what you guys come up with. Were you thinking of eventually starting a thread here on BoW?