Operation “Sea Lion” Invading England In 1940? [Part Two]

November 14, 2016 by crew

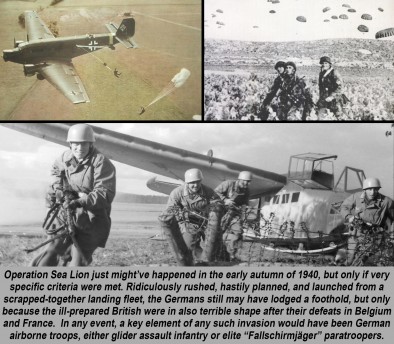

Last week, we embarked on an exploration of Operation Sea Lion, one of the most fascinating and debated invasions that never took place in World War II. In summary, Sea Lion was the proposed German invasion of England in the late summer of 1940.

Western Europe had just been crushed in a stunning German blitzkrieg, and carrying the offensive across the English Channel to topple the United Kingdom seemed, for a brief window, to at least pose a tantalizing (and terrifying) possibility.

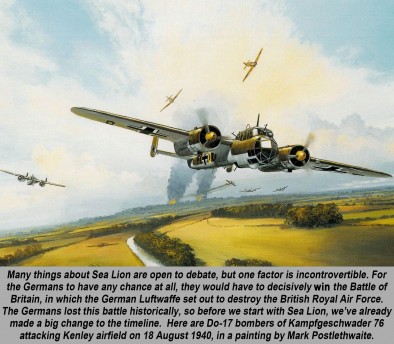

Obviously, this invasion never took place. The German Luftwaffe (Air Force) failed to defeat the British Royal Air Force (RAF) in the epic Battle of Britain. Without air supremacy, German prospects in any cross-channel invasion were nil.

But what if the Germans had won the Battle of Britain? They came very close, after all, and such a victory could have opened the door for a “Sea Lion” invasion as we’re exploring here. In Part One of our series, we took a quick summary overview of this operation and previewed (in broad terms) some of its prospects.

Having set the stage, however, it’s now time to actually “give the go-code” and launch this hypothetical World War II invasion of southern England. Based on factors of the time, actual German plans, and the forces that would have been involved, this is a wargamer’s view how Sea Lion could have actually happened.

S-Day: September 15th, 1940

In the predawn darkness over the shores of Sussex and Kent, the roar of surf steadily fades beneath the massed drone of hundreds of German aircraft. The date is September 15th, 1940 ... set by the German High Command as “S-Day,” the code word for the opening of Operation Sea Lion. The invasion of England is on.

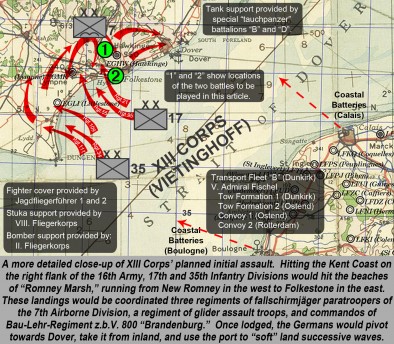

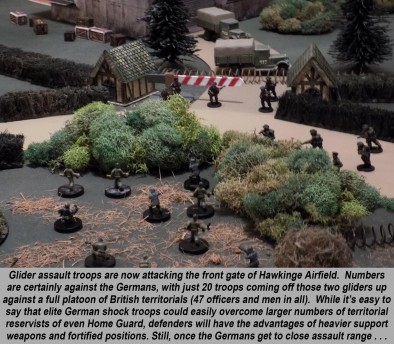

Our initial two battles will be fought along the east flank of the German invasion, near the vital port town of Folkestone. First, we’ll see German glider assault troops try to take Hawkinge, a badly-damaged RAF airfield just behind Folkestone, then watch 17th Infantry Division actually hit the beach just west of this critical objective.

With the RAF largely destroyed (or driven back to airfields in the Midlands and Scotland), and their radar warning network reduced to wreckage, the British can do little to intercept the initial phases of this invasion, which is delivered not from the sea...but from the air.

One of the initial targets the Germans have selected for their airborne drops is Hawkinge Airfield, just a few miles inland from Folkestone. A glider assault force of 7th Airborne Division has been detailed with taking this former RAF field, so dozens of waiting Junkers Ju-52 transport planes can bring in larger elements of German light infantry.

Hawkinge has had an RAF airfield since World War I, and served as an important staging point during the invasion of France. During the Battle of Britain, it was eventually put out of action by heavy Luftwaffe attacks, but now it may serve as a “staging airfield” for the enemy.

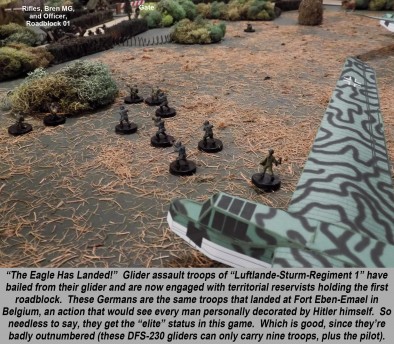

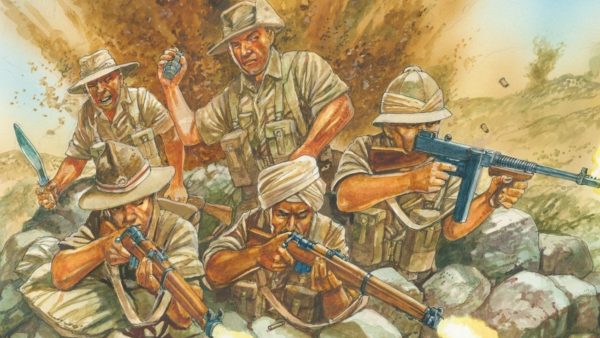

German airborne units fell into three broad categories. These were “Fallschirmjäger” paratroopers, “Luftlande-Sturm” (air landing assault) glider troops, and divisions of light infantry who were simply shuttled into captured enemy airfields via waves of Ju-52 transports. Of course, those airfields (like Hawkinge) had to be taken first.

Of course, Hawkinge airfield was just one target the Germans have struck from the air on S-Day. By 05:00 hours, paratroopers of Kampfgruppe “Meindl” (containing the bulk of Fallschirmjäger Regiment 1, or “FJR 1”) have also landed at Hythe and secured crossings over the Royal Military Canal.

Taking all the bridges over this canal is crucial, since it now seals off the British ground troops holding the beaches along the Romney Marsh, the main landing zone of XIII Corps.

Meanwhile, Fallschirmjäger Regiment 2 (FJR 2) has landed north of Postling, holding crossroads against any British counterattack from the north. FJR 3 has been detailed to secure the western flank against any British counterattack mounted from Sussex, detaching one battalion to take Lympe airfield, to be used to insert 22nd Air Landing Division.

Throughout the towns and villages of Kent, fighting is heavy and confused throughout these morning hours. The major British unit in the area is 1st London Division (XII Corps, Eastern Command), a Territorial unit NOT sent to France. Thus, they never lost most of their heavy equipment at Dunkirk and so make a good account of themselves.

One particular example is along the Royal Military Canal, where Kampfgruppe “Meindl” of FJR 1 actually fails to take two bridges, bloodily repelled by the London Irish Rifles (1st London Infantry Brigade). An emergency call is made to a German “kampfgeschwader” bomber group, however, who destroys the two bridges instead.

Yet while this air strike secures the Romney-Folkestone beaches from potential British counterattack or reserves, it also means these bridges will not be available to facilitate any subsequent German breakout once XIII Corps hits the beach (17th and 35th Infantry Divisions, already landing on the assault beaches).

Almost everywhere else, however, German success is swift. Although suffering high casualties in places, objectives like Lympe airfield, Postling, and Paddington are quickly secured by fallschirmjäger paratroopers and glider assault troops. By 13:00 hours, lead elements of 22nd Air Landing Division are being deployed into the bridgehead.

And as we’ve seen in our Battlegroup skirmish game, the German detachment assigned to take Hawkinge field has been successful. Although damaged in previous weeks, engineers will soon have this field in service. Two squadrons of Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighters will be based here, part of the vital air cover for further stages of the invasion.

Beaches Of Folkestone

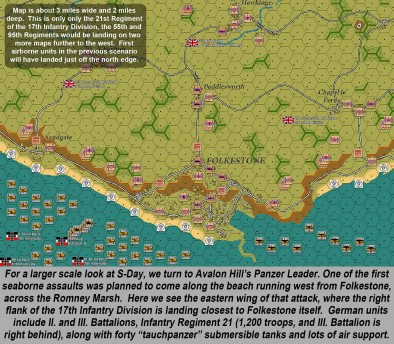

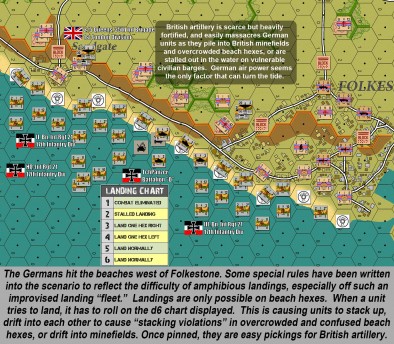

While glider assault troops and fallschirmjäger paratroopers were hitting vital targets overlooking the invasion beaches, the first waves of German seaborne infantry were hitting the beaches themselves. Among these, the 17th Infantry Division (XIII Corps) landed along the “Romney Marsh,” extending west from the port town of Folkestone.

As wargamers, the first thing we have to understand about these Sea Lion “beach landings” is that they wouldn’t have resembled anything at Normandy. Folkestone was no Omaha or Sword beach. There Germans have not taken two years to build a 5000-ship invasion armada, and the British have nothing like Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall.”

Rather, this is a very rushed and improvised landing force hitting a rushed and improvised beach defence. True, relics of Britain’s coastal defences can be visited even today, just bear in mind that almost all of this was built in the winter and spring of 1940-41. In September of 1940, we’re just looking at some dugouts, mines, and barbed wire.

Nor do most credible historians put must stock in fantastical ideas of a secret petrol-pumping system that would have lit the English Channel on fire. Such an idea didn’t work for the Israelis in 1973 in the Suez Canal, a body of water 1/100 the size, without currents or surf, and after six years of preparation. It wouldn’t have worked here.

Records of Churchill’s order to use mustard gas on German invasion troops are a little more credible, but not in the early fall of 1940. First of all, sufficient stocks of such chemical weapons wouldn’t have been available since they were destroyed by treaty after World War I. Also, civilians had not been evacuated from these coastal areas.

The simple fact is that British coastal defences in September 1940 were thin and brittle. The coastline open to possible attack was twice the length of the French and Belgian borders the Germans had just overrun, and the British now had to hold it with one-quarter the troops and one-tenth the heavy equipment.

That said, the Germans would have had the devil’s own job trying to cross the Channel in their “invasion fleet” of converted fishing boats and river barges. Even if they owned the sky, they would have taken terrible losses just getting out of the water. On both sides, this would have been “Normandy: Amateur Hour.”

Again, German tactical air power offers the only real hope such landings could have been carried off. However, the Luftwaffe would have been tasked not only with supporting the infantry, but also protecting the invasion corridor from the Royal Navy, and protecting the airborne landings.

How well could they have accomplished all three missions...at once?

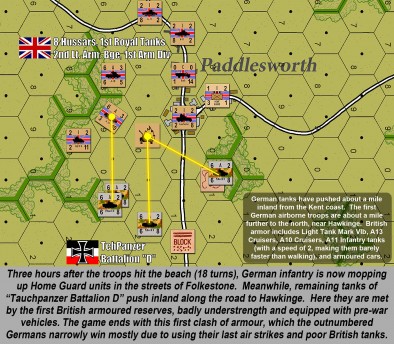

The Germans had a few surprises ready for the beaches, though. Among these were the “tauchpanzers,” tanks modified to travel for a short distance underwater and crawl up onto the beaches. Four battalions (160 tanks, mostly PzKpfw-III variants) were ready for S-Day, designated battalions “A” through “D”.

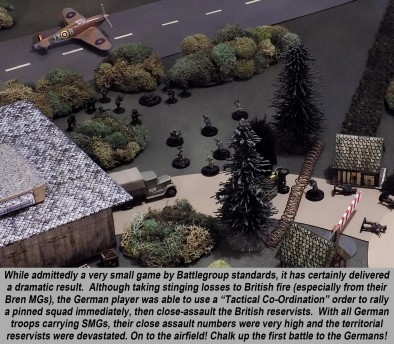

In our Panzer Leader game, the Germans took predictably heavy losses trying to get ashore. Only Luftwaffe airstrikes (and off-board artillery strikes called in from huge 12” and 15” guns in Calais) were able to suppress British coastal artillery emplacements.

Once a foothold was established, however, the game was up. Outnumbered British regulars, territorial rifle units, and even Home Guards were no match for a “First Wave” German infantry division like the 17th.

Folkestone was soon outflanked and taken, opening a port for heavier German units to land on S+1, including panzer formations.

What do you think of our Sea Lion scenarios so far? The Germans may have managed a lodgement here, but this is just a small part of the invasion front, and the campaign has a long way to go.

Keep the conversation going in the comments below, and come back next week to see how far “Seelöwe” will actually go.

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"...it’s now time to actually “give the go-code” and launch this hypothetical World War II invasion of southern England"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"The simple fact is that British coastal defences in September 1940 were thin and brittle..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Pure Sci-Fi Nostalgia! War Rocket Review | Hydra Miniatures [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/unboxing-hydra-miniatures-war-rocket-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![Zenit Miniatures’ Samurai Warlords Now Live On Kickstarter [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/samurai-warlords-launch-main-600-338.jpg)

Great read just as last week! 🙂

Have you taken into account random factors such as weather, bad comms, current etc?

Great questions, @neves1789 –

Have we taken into account …

1) Weather – in a larger sense, no. I’m taking the assumption that the Germans simply wouldn’t go if the weather wasn’t at least initially favorable. As we see with “Adlertag” during the Battle of Britain, the Germans (like almost anyone) simply postpone an operation if the weather’s not good. Since we’re showing Sea Lion launching, we’re assuming the weather is good on September 15 (or whenever S-Day is to take place).

D-Day was originally slated for June 5, 1944. The weather wasn’t great, they pushed it back a day. D-Day games don’t usually offer the chance for big storms damaging the Allied landing fleet. The fact that the game is on, assumes that the landings are a go, in turn assuming the weather is at least tolerable. Otherwise, simply annotate that S-Day is September 16 or 20 or whatever. 😀

On a smaller scale, yes. Para-Leader games involving gliders and paratroopers (not included in this article for space consideration – but I hope to include them in the support thread) do have detailed rules for low wind, medium wind, and high wind, wind direction, glider drift, paratrooper stick scattering, etc.

2) Bad communications – not really. Early in World War II the Germans were very good at this, Stukas were on taxi to provide almost immediate pin-point strikes on specific targets thanks to Luftwaffe liaison officers embedded in Wehrmacht ground units. Now, we do have a long delay for German “off shore” bombardment, two entire turns in Panzer Leader (15-30 minutes, depending on how you play). Also, only battalion “CP” units can call in fire missions from these distant (but very powerful) batteries. If these CP units are hit, dispersed, or sink due to failed landing checks, fire missions can no longer be called in. Further, if the unit that made this call is subsequently hit or dispersed before them fire mission impacts, it “drifts” or “scatters” per the standard Panzer Leader rules. I’ve absolutely had artillery fire missions drift onto my own units in past Panzer Leader games.

3) Currents – absolutely. If you look at image 9 in the article, you’ll see a small inset with a d6 chart. Some of the results in this chart direct a German unit attempting to land to hit the beach left or right of its intended hex. This can be disastrous as many of these beach hexes are mined. Some may be selected for bombardment (resulting in shelling of friendly troops). They can also cause stacking violations (only a certain number of units are allowed in one hex). Whenever this stacking is exceeded, the owning player must discard one or more of his own units until the hex is once again “legal.” This represents chaotic and overcrowded landing beaches, landing boats foundering, vehicles and equipment being pitched into the surf, etc.

These are ROUGHLY the same rules given for scenarios like Gold Beach and Omaha Beach in the original Avalon Hill Panzer Leader game – we just made them much tougher for the Germans here since their “invasion fleet” was nowhere near as well-prepared or designed as the Allies’ fleet of 1944.

Wow! That was almost another article on its own!

Well, I’ve always appreciated it when people post in the comments it gives me a chance to “fill in the gaps” I wasn’t able to cover in the article itself. And you should see some of the monolithic “walls of text” @jamesevans140 and I have been trading in Article 01’s thread. 😀

Just finished reading a book about so this made great reading

Thanks very much, @wolfkind. I hope the articles measure up! 😀

Now, that’s exactly how I put the puzzles together in my head after last week’s deliberations in pt1. I do like the fact that so many various factors had been put into the thing including this table connected with the beach landings. Yet, I am intrigued, since I am not really aware of how the British OOB looked like at that time, where was the force that would presumably be used to push sie Germans back to the sea as for example would have happened in Normandy a few years back if only some people would listen to Rommel. I assume these units would have some problems with pushing towards the beaches due to German air superiority. Was there nothing the Brits could throw at the Germans after the breakthrough at the beaches?

Thanks, @yavasa – Glad you liked the article, and how we handled the beach landings. Now we also take another look at the beach landings in Part 3 – through miniatures instead of hexes-and-counters – so we can look at this from different angles. It also allows us to explore possible problems and ramifications of delayed / weakened landings due to Royal Navy interference (a factor that I feel would have been greatly mitigated, but never completely eliminated, via our presumed Luftwaffe air supremacy).

As far as British reserves and armored counterattacks go:

We do have some pretty detailed information on British OOB as of 13Sept1940. We’re looking at one full armored division (1st Armoured). 2nd Armored is forming, with brigades in two overall deployment areas. There are also a Canadian tank brigade attached to the Canadian Division, and a number of armored car regiments.

The problem is in determining how well these divisions were equipped. Famously, the BEF was regarded as the most modern and mobile part of the British Army in 1940, and they had to leave practically all their weapons and vehicles on the beaches of Dunkirk. How quickly the British manufacturing base could have made these losses good and re-equipped the Dunkirk evacuees once more into viable mechanized formations is an open question. Of course there would have been SOME reserves awaiting at British depots, but I think we have to assume many of the British tank formations would have been badly understrength.

Against this, the Germans are landing four panzer divisions in the second wave. In the Ninth Army sector we have Hoth’s XV Motorised Corps with 4th and 7th Panzer (7th panzer doubtlessly with Rommel still in command), and in the Sixteenth Army sector we have Reinhardt’s XLVI Motorised Corps with 8th and 10th Panzer Divisions. All of this is in addition to the 160 “tauchpanzer IIIs” originally landed with the first-wave infantry divisions (although we certainly have to imagine these “special battalions A through D would have taken steep losses during the landings).

Now in the context of this storyline, we are giving the Germans plenty of delays, losses, setbacks, and difficulties in getting these panzer divisions ashore (ports aren’t taken on time, port facilities are blown up in retreat, the Royal Navy is causing problems, etc.). So I’m not putting 4½ panzer divisions straight up against 1½ Allies tank divisions.

That said, 1st and 2nd Armoured Division, and the Canadians, do make big showings in Parts 3 and 4. After all, what’s a WW2 article series on Beast of War without some tank-on-tank action? 😀 The British DO launch some pretty major counterattacks, stay tuned to see how they turn out!

Waiting for part 3 and 4 🙂 @oriskany

😀 That, and we’ll have the support thread up in the historical forums some time this week.

Well made, Sir! Very well.

Unfortunately my English is missing the right words to express what I have in mind…

Thanks very much, @setesch . Well, your English is a helluva lot better than my German, I just hope that “what you have in mind” remains good overall. 😀

It is indeed 😉

😀

@oriskany :

So not only do the Germans have to win the Battle of Britain, but they also have to make sure that they don’t damage the airfields they need too badly. However in doing so they might have given the British enough breathing room to survive.

This was a problem in the battle at The Hague too as the damaged air fields prevented them from landing as the troops they might have needed.

I think the Germans would have used ‘Hook of Holland’ instead of Rotterdam for their staging area.

It’s closer to the UK and it has had a ferry service since 1893 ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hook_of_Holland )

Excellent article as always though 🙂

Thanks, @limburger –

Indeed, from the beginning we’ve maintained sort of a two-sided, almost self-contradictory stance on the Battle of Britain and the state of the RAF in any reasonable discussion of Sea Lion possibilities in 1940.

On the one hand, yes, the Germans have to win, and you’re correct, you destroy an air force not bey shooting down all their aircraft, but by destroying their infrastructure, including (but not limited to) surfaced runways.

On the other hand, even a complete German “victory” here doesn’t destroy the RAF in total. As said in previous threads, limited range of Luftwaffe Bf109 squadrons based in northern France, Belgium, and Holland mean that daylight bombing runs cannot be escorted too deep into the UK. Results of Luftflotte V’s disastrous raids mounted out of Norway provide concrete examples of this. So RAF squadrons pulled back into the areas of 10, 12, and 13 Group / Fighter Command would still be in service if the Germans tried such landings.

As far as staging areas go, plans I’ve found show embarkation ports and airfields ranging from Cherbourg in the west all the way to Holland. The maps aren’t terribly precise, but they seem to extend to the Rotterdam area on the extreme east side of the planned invasion convoy routes.

Not sure where I mentioned Rotterdam, but I would agree that de Hoek van Holland (if that’s what you’re referring to) is very near to Rotterdam, and somewhat closer. I would question, however, whether the port and harbor facilities of de Hoek van Holland could stage launch part of an invasion fleet in 1940.

I don’t know enough either, but the Wiki says that to the Germans it was an important harbor location.

They probably would have used both. Rotterdam would be used for getting as many ships as possible and loading the lot, HvH would be the starting point of the actual attempt to cross, which kind of makes sense as that would have meant less time spent on open water.

At that time Rotterdam harbour probably wouldn’t have been as close to the sea as it is these days, so Hoek van Holland might have been a more practical choice.

One thing to keep in mind that during the invasion of the Netherlands it was Rotterdam that suffered a retalliation strike that pretty much destroyed the entire center of the city.

source : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotterdam_Blitz

Looking at the map (I’ve never traveled there myself) I’d agree with your comparisons of Rotterdam and Hoes van Holland. The damage caused by the Rotterdam bombing earlier in the summer also has to be considered.

Enjoying this series. As a Canadian I’m looking forward to parts 3 & 4.

Awesome, @littlejon . I think you’re going to like Part 4 in particular. 😀

Not being a military history buff myself, I have to say my favorite part of this article… In fact all the articles… is actually how you write them. You make your language vivid withou being outrageous or yellow journalism like. You paint a very vivid picture with your words combined with the pictures and the maps and I actually think I understand some military tactics! 🙂

Yellow journalism? I’d have to be a journalist, which I would never claim to be. Just a gamer who writes articles. 🙂 The truth is “purple prose” takes up word count, which is limited in these articles. Honestly, I never have “room” to be “gushy.” Just another case of “better design through constraints.” (with the credit for the constraints going to @brennon and the BoW team, not myself). 😀

Interesting landing @oriskany did you choose the marshes to confuse the brits or is that part of the documented landings possibilities? Not any documented uses of the tauchpanzer in other battles?

P S I love postlethwaite’s artwork.

http://www.wehrmacht-history.com/heer/amphibious-vehicles/panzer-iv-als-tauchpanzer.htm

Thanks, @zorg –

The beaches extending from Folkestone, westward to New Romney are the indeed the “prime candidate” landing beaches for 17th Infantry and 55th Infantry Divisions (combined to make the leading edge of XIII Corps / Sixteenth Army). Towns like Sandgate, Hythe, Dymchurch, and New Romney would have been taken, followed by a pivot eastward to take Folkestone itself from the side. I believe in this way the Germans hoped to capture Folkestone and other ports across the invasion sector via inland approaches, and then use the port facilities to “soft land” heavier formations like second-wave panzer divisions.

Tauchpanzer IIIs were “famously” used on the first day of Barbarossa as part of 18th Panzer Division, part of Guderian Panzergruppe II, crossing the Bug River (June 22, 1941). From what I read, however, these had been modified from the Sea Lion design. And of course, the Bug River (formidable as it may be as a military obstacle) is certainly no English Channel. 😀

Aieee . . . that should read “17th and 35th Infantry Divisions.” Sorry about that. And yes, Postlethwaite’s artwork is great and deservedly well-known, so I wanted to make sure I gave proper credit. 😀

similar to when the Canadians tried to take Dieppe.

I’m only 50% well-read or so on Dieppe, but yes, I’m pretty sure taking the port was part of the plan, at least temporarily. Of course Dieppe wasn’t supposed to be any kind of a permanent invasion.

That whole operation has always baffled me. Too big to be a raid, too small to be an assault. You can’t even claim political expediency (i.e., to show Stalin that the Western Allies were doing something). If it had been a successful “dress rehearsal,” all it really does is show the Germans your tactics, methodology, and overall plan of attack.

British and even Americans were involved at Dieppe too, the first action of the US Rangers I think.

yes they were lucky more people never died in the raid didn’t a unit get wiped out a week or two before on a practise landing when a E-boat squad attacked the landing boats sinking most of them.

I honestly don’t know, @zorg – I’d have to read up on it. 😀

One of the points I have seen debated on and off is whether or not Hitler chose toallow many of the allied forces to escape at Dunkirk because he wanted Britain to sign a treaty or surrender of some sort. If the plan was always for an invasion would it make more sense that the Germans would have pushed harder at Dunkirk and even less Allied veteran infantry would have been available for the period of sea Lion?

Don’t forget… Those Panzers heading for Dunkirk had to stop for a while… things needed to catch up.

Thanks, @jsaxty – and I agree with @piers . It bears noting that the infamous “Panzers in front of Dunkirk” is really only two divisions, 5th and 7th of Hermann Hoth’s XV Motorised Corps, and I’m not sure, but I believe Rommel’s 7th was racing further west. True, Reinhardt’s XLI Motorised Corps (6th and 8th Panzer Divisions) were rolling up the other side of the Dunkirk Pocket through Boulogne and Calais, but I don’t think they were really in position yet, to say nothing of the infantry divisions Piers mentions.

One view is that Hitler was watching the campaign very closely, probably too closely. He couldn’t believe the amazing success in his own army. The further ahead the Panzers race from the infantry divisions, the more vulnerable their flanks become. All the Allies have to do is snip these panzer columns off from the rest of the German Army, as indeed they tried at places like Arras and Crecy. Hitler may have also misinterpreted maintenance and breakdown figures as “combat losses,” and assumed his panzer divisions were in even worse shape than they really were.

One thing we shouldn’t overlook is the heroic defense that stalled German advances toward Dunkirk, most notably the French First Army at Lille. King Leopold III of Belgium also deliberately dragged out the surrender negotiations of the Belgian Army, delaying the actual moment of his forces’ stand-down, surrender, and demobilization, tying down still more German forces further east.

I will confess wholeheartedly, though, that in a larger sense the Germans (especially Hitler) expected the British to cut a deal after the Fall of France. German planning for Sea Lion went through a long period of “just in case” and “lets wait and see” while peace offers were repeatedly made to Great Britain.

I’m sure once the last German peace effort had been rebuked, they regretted so many Allied soldiers having escaped at Dunkirk.

it is documented that Adolf got the figures wrong about tank figures.

Great article and ‘what if’ gaming report. If the Germans had got a beachhead established at that early stage of the war I believe it would have been an incredibly bitter and hard fought occupation. Assuming Hitler concentrated on subduing Britain I don’t think things would have gone in the Allies favour and the casualties would have been horrendous. Thank goodness this never eventuated, as the British mainland would likely have been as devastated as the most heavily fought over European countries. By the time Allied forces took it back, which undoubtedly would have happened in time, Britain would not have been the same country it is today.

@spaced2020 – I couldn’t agree more. On the one hand, I’ve been maintaining on previous threads that I don’t think Britain was quite as politically stable as many remember, given our scenario of a British defeat in the Battle of Britain. To a large extent, it was this historical victory that put real iron behind Churchill’s words of “We will fight them on the beaches,” etc. Until that victory (which HASN’T come in this alternate timeline), there was a pretty sizable faction of Parliament who thought the Germans might really be unbeatable and it was unwise to further antagonize them. Best to cut a deal now.

EVEN IF THAT HAD HAPPENED, though, I think the average British soldier, reservist, and citizen would have fought with borderline suicidal determination. We’ve all heard the stories of British partisans, “pre-staged” to disrupt German occupation. Some of the measures that were in place for these resistance fighters is borderline horrific. They knew they were already dead. “Take at least one with you” was the standing watchword even for ordinary civilians with hunting shotguns and the like.

If the German campaign had reached as far as London, I think we see another whole dimension of carnage. Thus far, European capitals had fallen to the Germans in one of two ways. One, terror bombed into surrender (Warsaw, Rotterdam), or given up without a significant fight to spare the city and its citizens (Paris, Oslo, Copenhagen). I don’t think London would have fallen into either category. We’ve seen them terror-bombed in the Blitz and they never cracked, and I don’t think it would have been given up. So what we get instead is a nightmare urban battle, complete with underground bunkers that are still in place to this day. “Stalingrad West” as I’ve called it on previous threads.

Lastly, the historical pattern shows where German occupation was the most cruel: Poland, Yugoslavia, Belarus, France later in 1943/44 . . . where there was a significant resistance / partisan activity. As late as the winter of 1944-45, we can see the revenge the Germans took on the Netherlands for helping the Allies in Market-Garden.

Given what the British had prepared in the way of resistance, and the plans guys like Reinhard Heydrich had for Britain (we’ve all heard stories of his “List”), I can’t imagine that any German occupation of Great Britain, no matter how brief or how small an area, would have been horrific. I don’t think we can use the relatively benign German occupation of British territory in the Channel Islands (Jersey and Guernsey) as examples.

yup would have been as bad as the marines taking japan I think. @oriskany

Assuming the British government stands . . . yes. We must remember that in this scenario, they would not have been electrified by success in the Battle of Britain, and not comforted by the promise of American aid. By and large the Americans were not betting on the UK until after the Battle of Britain was a success. In this scenario it must be regarded as yet another colossal defeat by a seemingly “invincible” German war machine.

It staggers the mind to conceive what direction the war would have gone during the early forties if Britain had succumbed to a successful German invasion/occupation. Who would have coordinated a successful retaliation against the Nazi warmachine in North Africa? Would Britain have been able to undertake the Anglo–Iraqi or Syria-Lebanon campaigns? How would this have gone on to have affected the timing and available resources for Operation Barbarossa? Who would have consolidated and commanded the remaining Commonwealth forces? The Battle of Britain was such a pivotal point in the war. Fascinating stuff. Thanks again James for taking the time to show us how interesting world war two gaming can be.

Thanks very much, @spaced2020 – Indeed the alternate timelines very very unpredictable once you make a change as significant as a defeat or negotiated peace with the UK.

North Africa might not have happened at all. Italian 10th Army would have still invaded Egypt in September 1940, the WDF still would have defeated them, but without orders from London. I don’t think we would have seen an “Operation Compass” counterattack in December 1940.

We go over this a little in The Desert War Article Series, Part Two:

http://www.beastsofwar.com/battlegroup/desert-war-gaming-ww2-part-two/

We also have to look at how Britain’s exit from the war effects the disposition of her colonies in Asia, most importantly Singapore This effects Japan’s plans in 1940-41, and thus how (or if) America enters the war.

Assuming America enters the war after a Pearl Harbor or similar event, I think we can imagine a much more Pacific-centered strategic outlook from the US President and the Joint Chiefs. The American public wasn’t really interested in war against Germany, but they sure as hell wanted payback against Japan. It was only Churchill’s and FDR’s agreement on a “Germany First” policy (taken in the face of public opinion and military advisors) that brought the US into the European Theater (that at Hitler very kindly declaring war on us instead of vice-versa, that actually made FDR’s life as lot easier in that regard).

But would that have happened without Churchill or a UK? Could we have seen America only involved (at least initially) in a Pacific war?

when has the government stopped a fight don’t forget half of the battles in the UK were against the government or king of the time. @oriskany

I would agree that popular resistance might have smoldered on in the wake of a potential government collapse. But to actually wage a modern war, you need an army, factories, billions of dollars, infrastructure, an officer corps with 30-40 years’ experience . . . in other words, you need a government.

You can’t run “real” war by Kickstarter. 😀

true but would have been a hell of a gorilla fight to control the country for a while.

Another excellent, well researched and thought out article. Looking forward to III & IV

Joe90

What he said, the amount of research you put in to the articles are impressive

Thanks very much, @joeninety and @rasmus . Although, of course, in an “alternate history” project like this, research can only get you so far. Sooner or later you have to make a few guesses and take a leap. Which of course is what makes it so much fun. 😀

Thanks again. 😀

@oriskany A both fascinating and chilling read! Will you follow this article up with an article about a combined Nazi and Japanese invasion of the USA?

Thanks, @davebpg . 😀

Eh … believe it or not I have done some pretty serious work kind of along the lines you suggest. Frankly, I don’t there’s any kind of realistic scenario that puts German or Japanese occupation forces in the US (not really a fan of Man in the High Castle, etc). There are several plans out there, most of these are ironically concocted by the American press to frighten citizens into buying war bonds, etc.

The closest I’ve seen to any kind of German invasion of North America is Operation Mammoth (Mammut) – which basically entails an “island hopping” drive from Scotland to Iceland to Greenland to Newfoundland. The Japanese also have “Plan Z” with possible landings at the Panama Canal (presumably after taking Hawaii and Alaska).

But these “plans” I feel are more along the “Hitler is up at 4:00 AM in the morning, rambling and doodling on cocktail napkins” variety – much like “Plan Orient” where Rommel, Kleist, and the Japanese were all supposed to meet up in Afghanistan somewhere.

Please understand, this isn’t inflated American pride saying we are unconquerable or we couldn’t have lost the war. I feel a German victory in WW2 entails conquering both the UK and the Soviets, resulting in a “Cold War” between the US and the Third Reich much like the US-Soviet Cold War of history. We may have held a strong lead in atomic weapons but the Germans had the better rocket technology,and the Germans could have caught up much the way the Soviets did in the late 1940s and 50s. We may well have found ourselves in a “Brazil Missile Crisis” like the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. I don’t think that a 1960s or 70s Reich would have hesitated to nuke us.

There are “real life” plans for World War 2 ground combat in North America. Most infamous is probably the American “War Plan Red,” which entails the invasion of Canada. It sounds silly, but these plans were drawn up and taken very seriously early in the war. The reasoning was . . . what if Great Britain is defeated and forced to cut a deal? What parts of her Empire / Commonwealth might she be forced to hand over to Berlin? We’re NOT having a German foothold on the St. Lawrence River . . .

Finally, some friends and I have tinkered around with the idea of a scenario whereby a big, big part of World War II takes place in the Continental United States. Like we did with Lloydoslavia 1985 for the Team Yankee Boot Camp, the trick is to rewind the clock far before your intended “historical target” and make a few smaller, more realistic changes that EVENTUALLY lead to a radically different world-view where your scenario (however preposterous it sounds at first) suddenly isn’t so crazy.

Put most simply, this “Panzer Leader ATO (American Theater of Operations)” describes a different outcome in the American Civil War in 1862. With multiple republics now standing where the US does in real life, these republics wind up on different sides of World Wars I and II, and while the Germans never actually “invade” the US, they do have allies here and send advisors, observers, U-boat bases in the Caribbean, etc.

But that would be an entire wall of text itself, so I’ll stop there. 😀

Many possible scenarios to consider. What’s certain is that had the uk fallen, the government and royal family would almost have certainly escaped to Canada. I doubt the surrender of the uk, and I guess Ireland, would have caused Canada to capitulate as well. I would imagine the uk colonies would have done what they good against their respective invaders, Indians and Australians against Japan for example.

A combined mainland invasion of Mexico by the Nazis and the Japanese would have given the axis powers a “soft under belly” of their own to launch attacks against mainland USA. Shame Trump isn’t on hand to supervise wall building but that’s for another article lol.

I agree about the prospects of the UK Commonwealth / Empire. I think Churchill said in a speech: “And even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it, were subjugated and starving, the British Empire, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, should carry on the struggle until, in God’s own time, the New World steps forward to the liberation of the Earth.”

Translated: “Even if Britain falls, the Commonwealth will continue to fight until America gets it ass in gear.” 😀

There were indeed plans for move big parts of the government and the Royal Family to Canada. Whether Churchill would have left or not is an open question. This was a guy who personally wanted to leap from one of the first landing craft on D-Day, mostly in a snit because his emphasis on Italy had been overruled (he only backed down when King George VI promised to be in that landing craft right beside him).

There were also plans / discussion on the German side (I have no idea how concrete these were) to have Edward VIII come back after his 1936 abdication and rule a subjugated England as a Vichy-type puppet, or perhaps ruling over a part of Great Britain left unoccupied (again, in a Vichy-type model). These were based on the assumption King George VI and his family would either be dead, imprisoned, or escaped to Canada.

I’ve already gotten in trouble talking about Trump and his wall this week. Time to behave myself. 😀

Now that is news to me – the Edward VIII thing – and just the kind of crazy thing you’d expect the Nazis to think would work.

I hear you, @spaced2020 – it sounds pretty absurd. Like I said, I have no idea how concrete these discussions / plans were. I think part of it stems from a strange view many in the Nazi leadership held for Britain. There are just certain things that HAVE to be.

“Even if we conquer them, they’ll need to have a Royal on the throne, right? England ALWAYS has a king or queen.” ??? Right??

@oriskany another interesting article, on a side note it remined me just how unequipped the British were in 1939, as i have seen all the records in the Imperial War Museum that showed that the all the servicable weapons etc that were held in the IWM from the first world war were requisitioned by the British Army in 1939. Most being then left in France. So I wonder just how well equipped the Soldiers post Dunkirk actually were.

Couldn’t agree more, @commodorerob. In references I keep seeing the BEF described as “the most modern and mobile” part of the British Army, and while 240,000 British troops may have been evacuated from Dunkirk, almost all their equipment and vehicles had to be left behind. So while the British have enough manpower to field 20-30 divisions, there isn’t that much with which to equip them.

The basic model that seems the most realistic is for the better-equipped divisions (the ones that hadn’t been sent over to France and Belgium with the BEF) to give up some of their equipment to be spread around the others, so all the divisions have at least something with which to make an account of themselves. The better divisions are placed in the most threatened sectors (Sussex and Kent) with the best commanders (the OOB in these areas have all the big British names as corps commanders, Alexander, Auchinleck, Montgomery, etc).

I think it’s important to remember, though, is that this is a pretty thin crust. Once these divisions are cracked, the rest of them have very, very little. Even these front divisions are badly off. That Panzer Leader game has only two coastal batteries for a coast of 4 miles (6-8 guns total), two batteries of 2-pounder ATGs, no bunkers, a few minefields, and some “IPs” (Improved Positions) – basically sandbags and barbed wire. Any artillery is going to be WW1 era 18-pounders of 18/25 refits. Even most of the infantry on that board are territorial reservists or even Home Guard.

While German difficulties would have been extreme, what balances this out (at least in the short term) is the defense they would have been landing against. Certainly it would have been determined. There would have been a lot of men, and these men would have fought as hard as they could. But the divisions, and their commanders, would have been so badly under-equipped. And if the Germans controlled the skies . . .

Still one man and a pointy stick can cause a lot of irritation… They don’t like it up em you know 😉

😀 “They don’t like it up em you know”

Ehh . . . the less I know the better. 😀

Once again love your info, Maps and Deployment of British forces looks spot on.

Could we have held at that time ?????

Man with twig in helmet, “Wrong kind of cammo for built up areas”.

Thanks, @nosbigdamus – Later this week I’ll be starting the parallel “support thread” in the historical forums. In this thread I’ll be able to post some of my sources, including a great map that shows where the British divisions and brigades were deployed in September 1940. I also have some pretty detailed maps of German invasion plans (especially in the New Romney-Folkestone area) I’ll be able to post. Hopefully the community will find this stuff interesting.

That reminds me of Anthony Hopkins in A Bridge Too Far. 😀 When they get to Arnhem, he mutters . . .”I just realized something. We’re wearing the wrong kind of camouflage . . .:”

Really like this idea, exited for the next one, number 3, you do put out shockingly good stuff.

Thanks very much, @nosbigdamus . 😀

Yes wagons roll. Great second installment @oriskany. I think your simulation of lodgement worked out well. Some parts went to plan, a few things went better than planned and finally the things that unexpectedly went wrong causing issues for the next stage. This is the striped down script for historical landings, so your close to the mark.

The burning of the channel by secret pumping stations was one of those stories going around and becoming myth. Like most myths there is some truth in them. The truth is there were pumping stations, many of them all over southern England. They were part of an underground refueling system for the RAF. Fuel was pumped to underground storage next to major air field. These storage tanks could also be pumped dry moving the fuel elsewhere. Parts of this system is still in use today. I don’t know if the burning of the channel was a cover story or completely unrelated. It was started by Bomber Command but was expanded across southern England and included Fighter command bases as well. By late 1940 it was in a very advanced state of completion. Imagine the Germans capturing one of these bases and being excited over the huge amount of fuel that they got, only to find them empty the next day.

The defences could be very brittle indeed. During the Battle of Britain I read one account of a whole channel beach being protected by the great might of 2 rifles. I think this would represent one extreme end of the spectrum.

So for our campaign it starts on September 15. What would be of great use to us are your very large scale maps if you take the time to mark in the front line off advancement by date. The time intervals are what best suits your campaign. Whether is it every few days, weekly or what every else works for you. This way we will know the rough date of say when a town falls cutting off communications and supply to a given area. We would also know the positions of the regiments or battalions of both sides. This would let us know what kind of possible backup our Home Guard might get and how much pressure the Germans could apply to them.

Greatly enjoyed the read and it conveyed the desperation of both sides on S-Day for both sides.

Unfortunately my breakfast read was shattered by the unexpected invasion of the grandkids for the day, so I have been hanging all day to get back to finishing reading this.

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this @oriskany and it gave me some ideas for our project. Really looking forward to the gaming thread for this installment.

:-D. :-D. 😀

Good afternoon, @jamesevans140 –

Great post. 😀 Let me try to reply point by point …

I think your simulation of lodgement worked out well. Some parts went to plan, a few things went better than planned and finally the things that unexpectedly went wrong …

At the risk of overgeneralizing, I’m of the opinion that both sides in a September 1940 scenario would have been woefully under-prepared and ill-equipped for their respective missions. This is a recipe for total chaos. But the side that usually manages to pull the win out of chaos is the side that has the better low-level commanders, the better NCOs, senior sergeants, lieutenants, and captains. In 1940 this is DEFINITELY the Germans. This is the reason I think the Germans really would have had a shot . . . at least for the INITIAL landings.

As far as S-Day +5, +10, and +20 go, however . . .

The burning of the channel by secret pumping stations was one of those stories going around and becoming myth. Like most myths there is some truth in them.

I didn’t know about the underground pumping stations for the RAF. But I do know the British had this “light the invasion waters on fire” system, I’ve seen footage of them testing it. When it was in place, however, I don’t know. I find it hard to believe it could have been built in 2-3 months. Even if it had, I feel that examples of similar systems, used with YEARS of preparation in far more suitable conditions (1973 Suez Canal) show that it wouldn’t have effectively slowed anyone down.

The defences could be very brittle indeed. During the Battle of Britain I read one account of a whole channel beach being protected by the great might of 2 rifles. I think this would represent one extreme end of the spectrum.

Agreed. I feel the depiction of our Folkestone landing exhibits the other extreme. This is about as THICK as these defenses would have been. I have two fortifications set with coastal defense guns, and about 2000 British (regular army, territorial reservists, and home guard) set up for the defense. I even have a small armored counterattack force (hey, the name of the game is PANZER Leader, after all). 🙂 This is one of the obvious landing beaches, though, so I don’t think giving the British the benefit of all these doubts is too unrealistic.

And I apologize if I keep repeating myself here, but we should remember the British are decrypting Enigma messages, so no matter how weak their defenses may be, if the Germans actually launched this invasion, the British would have almost certainly know exactly WHERE they were landing. This would allow them to scrape together available resources (shallow as they may have been) to meet the threat.

What would be of great use to us are your very large scale maps if you take the time to mark in the front line off advancement by date.

I actually hadn’t planned on it, but sure, I could do this. The German and British divisional markers are “floating” over a map of SE England in one of my Photoshop files, I could come up with a slide-show of sorts, showing where these divisions are on different days, etc. Like I said above, I promise to get that forum thread going sometime this week.

Sorry (and glad) to hear your Operation Sea Lion invasion was usurped by the far more important Operation Grandkids invasion. 😀 Have fun!

Building up nicely, can’t wait to see if I should speak German in your version.

Ja, wir müssen Deutsch sprechen!

Yep I had m my own invasion. It starred with ‘sorry for not phoning ahead but…’ so total surprise achieved, then came the mad rush to get some U.S.troops I am painting at the moment to much higher ground. It was a good day with the usual they came, they saw, the trashed the place. 🙂

The burning of the channel idea I believe comes from an idea dating back to the age of sail of burning the port waters. I read references to the idea but not of its defensive use, there are several references to its offensive use of fire ships into the port.

The chaos on both sides was perhaps a balancing factor along with the British army had only one good leg at the time. Totally agree with the low level tactics and command. At this point in the war I would add the imperial Japanese to their company and possibly the Finns.

As the Germans moved north along the coast I would love to see their puzzled faces when they came across huge multi story high concrete bunkers then as they got closer, no could they be moulds for making giant snail shells. A.K.A the acoustic listening posts that have been in service since the WW1.

It would have been a very savage affair if either side had the operational ability of the Normandy period. In so many ways that is a century away rather than just 4 years. Like in so many wars they were trained and equipped to fight and win the last war. They were still trying to recover from the last war and the great depression as well. So I don’t think they were even ready for the last war but Germany was ready to fight this war with the exception of invading England that was not on the blitzkrieg label.

To be fair this invasion went a bit better than Gallipoli and not quite as good as Norway. The fact is the textbook used for Normandy has not been written yet, this it’s doctrine on the fly. So yes it is amateur hour or dare I say it, it’s all a bit too much Dad’s Army.

Thanks for agreeing to produce those maps over time for us as they will be of great use for our project.

Indeed, @jamesevans140 – good ole’ fireships. Between the ships they burned to fend off the Spanish Armada, sinking ships in ports to deny Germans use of the facilities (thanks again for that idea @yavasa ), sinking ships as breakwaters for the Mulberry harbours, and crashing destroyers into German dry docks during the St. Nazaire raid, it seems the Royal Navy likes blowing up their own ships almost as much as the enemy’s. 😀

Stunning. Really enjoying the ‘what if’. I live in a town called Ramsgate in Kent and not far (1 mile) from RAF Manston (which was my last posting). I have a particular fascination with Operation Sealion as both of my grandparents and uncles aunties etc., lived in Ramsgate throughout the Second World War. I used to listen with fascination of the stories they told me and how, especially in the early stages of the war, it affected their lives. My grandfather worked for the railway and did up to retirement but was in a reserved occupation so wasn’t allowed to join up. Determined though to do his bit he did join up and did 8 weeks training before being arrested and sent back to his job. He then joined the railway LDF (Dads Army) which in 1939 consisted of many members but only one rifle and 10 rounds of ammo!!!! Ramsgate apparently was the most bombed town on the south coast due to the fact being close to RAF Manston and any aircraft returning to France would unload all of their unspent ammo on Ramsgate. My father picked out an unspent ME109 round from his sisters bedroom wall, he was 4 or 5 around 1940. Boys being boys him and his mate took a hammer and nail to the rear and it went off. Burnt his hand and blew half of the vice away. Its stories like that, that I grew up with. The real history, the human side civilian side, the bit that doesn’t get talked about as much. I have many more ‘stories’ but I am in danger of becoming boring so I will pause for now but thank you and I look forward to part 3 🙂

Apologies, just shown my Dad this and he has corrected me. Him and his mate found the unspent round in his front garden. But a lone fighter unloaded a whole load of ammo into his sisters bedroom, while she was still in bed. Apparently she woke up after the event covered in plaster. I stand corrected 🙂

The round blew up when they messed with it? Man, it must have been one of the 2.0 cm (MG FF) cannon rounds, I’m guessing incendiary or explosive (most pilots liked their cannons armed with a varying mix of ammunition types).

We’ve heard from a couple people now who live right around these proposed invasion zones. So (a) I apologize again if we blow up anyone’s house. 🙂 And on a more serious note, (b) I hope this comes across with due respect . . . to both sides . . . because YES, we have people from both nations reading these.

Looks like most of our ground fighting will be taking place to the southwest of Ramsgate. In about every version of the plans I’ve found, the planned invasion routes start near Folkestone and extends westward from there. How far depends on the versions of the plans, some go as far as Hastings, others as far as Southampton (both these extremes are a little silly). That said, of course air combat during the Battle of the Britain ranged all over!

Sounds like your Dad and his sister had a pretty harrowing experience.

As you may see in the Panzer Leader maps, we’re featuring three basic types of British infantry . . . Regular Army, Territorial Reserves, and Home Guard. Home Guard was the lowest values, but please understand this isn’t due to any disrespect, etc. Each piece in this game is a platoon, and while a Regular Army platoon might represent:

REGULAR ARMY PLATOON:

x1) officer

x2) NCOs

x36) Other Ranks

x3) LMGs

x1) antitank rifle

x1) 2-inch mortar

HOME GUARD PLATOON:

x1) officer

x1) NCO

x20) other ranks

** (each with 1 rifle and only 10 rounds of ammo, as you’ve said).

This is where the differences in numbers are from. Still, as we learned in our Folkestone landing scenario, if the British player can keep his Home Guard platoon in urban hexes, improved positions (or even better – in a fortification) and covered by friendly mortars, etc., they can really slow down the German advance and prevent them from taking key objective hexes (port hexes, etc).

First of all no offence taken. I’m well aware from my grandfather and uncles that the Home Guard had many shortcomings. That one rifle I mentioned before, my Grandfather told me that they used to take it in turns to carry it. One day they heard a load bang in the booking hall and raced up there to see what had happened and the booking clerk had put one up lent it against his desk, it fell over and the round went off. All my granddad could think about was that they were now down to 9 rounds. He eventually became platoon sergeant and was issued with a Thompson. He said he felt like an American gangster lol. There HQ was an old railway carriage without wheels and that ended up in my great grandfathers garden!!!

One thing you don’t take into account though is the local population. My Nan said if the Germans had invaded she had many she would use, from sharp knives to garden forks and boy was she serious, her face would glaze over and she had this strange look as if she was there again. So yes many others felt the same way as her, she even knew how to make a Molotov Cocktail!!! I never looked at my sweet little nan the same way 🙂

Had a read of your comments and the recollection of your relatives experiences. Always interesting to hear how folks lived during those times, so thanks for sharing.

Good afternoon @minty45 and @spaced2020 –

“He eventually became platoon sergeant and was issued with a Thompson. He said he felt like an American gangster lol.”

The Thompson M1928 / M1A1 is indeed a beautiful weapon. Expensive to produce in military quantities, though especially once EVERYONE in the western world wanted one. I think this is the reason they started with the M3 “grease gun” eventually, a much, mcuh cheaper SMG. Even the American economy can’t make Thompsons for everyone who wanted one 1940-45.

“One thing you don’t take into account though is the local population.

Actually, we just haven’t gotten to it yet in the articles. 🙂 Please bear in mind we’re still on S-Day. Now, in the comments it’s been discussed at length, also in Part One and in the Weekender thread. We talk about these “British partisan” guerrillas getting the standard order: “Take two or three with you.” These men knew they were going to die. There’s also been commentary on the mood of the people awaiting invasion, including the writings of a novelist Margery Allingham, who lived with her husband along the Romney coast. She and her husband had a old 1800s revolver with just three or four bullets. Their promise again . . . “take two or three with you.”

The further challenge we face with this is that these are the kinds of things one sees when an area passes out of a “battlefield” phase to an “occupation” phase (i.e., after the Germans have won, like I told Justin during the Weekender interview). We’re focusing more on the battlefield part. Also, if I say definitely whether I am including British partisans, I’m sort of “pre-spoiling” which way the campaign will go. If I say they will be included, it’s clear the Germans will win. If I say we won’t include partisans, than the British are winning. 🙂

Good evening @oriskany.

The first I read of sinking ships in the harbour was one of the wars against Holland in the age of sail. The British had sunk ships and other obstacles in the Thames river. The Dutch sent a raid on London and got snagged on sunken ships becoming easy prey.

The British isles have a very long history of being invaded, some successful and others not. So they are quite experienced at dealing with unwanted guests.

The RN have long used the Home port strategy. This is basically take the war to the enemy’s home port to force the enemy to withdraw his forces to defend his capital. This strategy has been around for a long time of coarse as it worked for Rome to get rid of Hannibal. It might be worth looking into this for a follow-up set of article series with this strategy especially if this one is non conclusive with German forces still on their soil. Although i think it would be extremely hard for the British having lost most of the RAF and Germany controls the air and has a strong anti navy force available to it.

I must fly as I have things to paint. 🙂

The British isles have a very long history of being invaded, some successful and others not. So they are quite experienced at dealing with unwanted guests.

Indeed, there have been more successful invasions of the British Isles than unsuccessful invasions. Caesar failed, the Spanish failed. I guess with the Battle of Britain, you could say Hitler tried and failed (depending on your definition of what an attempted invasion looks like). But then we have William the Conqueror who succeeded, Claudius who succeeded, the Saxons who succeeded, the Vikings who succeeded . . .

And none of these people had huge “Normandy 1944” invasion fleets. While I would agree that any German attempt at Sea Lion would have been rushed, half-baked, and slapped-together, I still think it bears noting that the British defenses in 1940 were even worse, and t hat at least an initial lodgement was definitely possible.

Where it would have gone from there, however, remains a much more daunting prospect for the OKW, Army Group A, or really any faced of the German command structure or military effort in the British isles. Landing on a beach is one thing. Conquering Britain in a modern mechanized war is another.

The more research I do on this the more I realize the Royal Navy didn’t stand a prayer of stopping at least the initial (repeat: INITIAL) crossing. The British Army was also in even worse shape than I originally thought. Indeed, the RAF was the only branch that could really stop Sea Lion’s INITIAL phases, which of course is historically what happened.

Once we get into October, however, once the German have to start moving thousands of tons of supplies a day across the Channel (instead of just tanks and infantry), and once the Channel weather deteriorates to the point where the Luftwaffe can’t hold back British dreadnaughts and heavy cruisers . . . I think the shoe starts to shift to the other foot.

I agree @oriskany, I believe it is S+4 to 8 weeks things welcome interesting. In this period is here the RN has recalled the Navy to defend the Home Isle, with the possible exception of the Mediterranean Fleet as the Suez must remain open. Towards the end of this period the Commonwealth will begin to respond. Here Canada would be a big responder with its army and navy, admittedly a smaller and not as powerful as it would become later. Egypt and India are more interesting, sensing to overlord on it’s knees may seem opportunistic revolts to grab independence. India at this stage has no threat from Imperial Japanese expansion so this might see them go for independence. If it looks like Britain may fall in this post invasion period going into mid to late fall then Spain and Turkey might be easily enticed off the fence. If this were to happen then British holdings in the Middle East could flare up in revolts. African holding I think would be a mixed bag of responses. Although I believe South Africa would try to send troops.

With Britain on her knees world politics start changing extremely fast.

Now that’s a “domino” effect I hadn’t considered, @jamesevans140 , some of the British colonies / dominions taking their chance to break away. The Germans were working in Iraq, trying to start trouble there. Palestine / Transjordan was already experiencing turbulence . . .

Interesting isn’t it @oriskany. As you know I like to look at a situation from minor tactics to grand strategy. The penny dropped when I started to consider the response from the commonwealth. First question was the condition of members and there ability to respond. This posed the question would they respond. Then what impact would Operation Sea Lion have on countries that were technically neutral but sitting on the fence, so to speak. As an example Henry Ford was using his influence to keep the US either neutral or on the German’s side of the fence. The underlying reason is simple. All the contracts that made the most money outside the US were held in Germany. The British contracts were small as the British were not spending.

Once we look at the impact that Operation Sea Lion would have on the Grand Strategic level could easily have more impact than the invasion of Poland on the world stage. Take a look at the impact of the French colonies had. The handing over of Indo-China to the Japanese and the planning of operations in the Mediterranean had to consider responses of Vichy controlled colonies. The British Commonwealth Colonies would have far greater impact. The British Commonwealth Dominions such as Canada, South Africa and Australia are free to make their own decisions. So it turns out that Operation Sea Lion has far reaching effects than simply the last European power to fall to Nazi Germany. Ouch.

Well, @jamesevans140 – I have finally just submitted Part Five to Beasts of War, so at least for my money they verdict is in. 🙂

Definitely agree about the lack of an American public opinion backing for the UK during this time. The opinions, writings, and communications of Joseph P. Kennedy (US Ambassador in London) certainly weren’t helping. I think opinion really started to change over here after the British won the Battle of Britain. But if they LOSE the Battle of Britain.

I certainly think the Italians would have been even more bold in their moves of August – September 1940 if the Germans were really invading or getting ready to invade. Egypt, British Somaliand, the Sudan, etc.

As far as the reaction of the Commonwealth, I think this is a mixed bag. Some would have been much more ready to jump ship, others may have become even more loyal in such a time of adversity (Canada, Australia, New Zealand).

J.P.K is an interesting biography in itself. Anti British to the extreme. Most comments sent back to F.D.R was tainted by this would view to the point of untruths. He quickly felt out of favour when F.D.R. sent one of his Skulls friends as part of his secret personal spy network to London for a second opinion and uncovered a different story. The main thing F.D.R was looking for was something that he called backbone. That J.P.K had been reporting it was not there, when it did. However this is politics, which I normally do not study. The politics of this period had major impact on geopolitics and need to be considered. I believe F.D.R had a much better understanding of geopolitics then those who surrounded him.

According to the British propaganda handbook the Commonwealth its a large family living in the same house. The colonies are the children that need the care of their parents until they grow up. The dominions are the adult members of the family still living at home. As far as things go this is a fair analogy.

In the colonies you find British government and military. The police force is British lead with the locals making up the rank and file. They have no choice to leave the Commonwealth. The dominions have their own government, military and infrastructure to function and have a choice to remain in the Commonwealth. Both have a governor general that outright rules a colony while they only have the power to dismiss a government in a dominion. So their can be a total feeling of occupation in a colony while the dominions are independent countries that has been raised to love and respect their parent.once developed a colony becomes a dominion. At this time India is quite interesting. It is a colony almost ready to become a dominion but it wants out of the Commonwealth now. But there is a duality as a large portion of the population wishes their own variety of dominion.

So the reaction from the commonwealth would be quite varied from its members. Those that feel occupied well grab their chance of freedom. While those that feel they are part of a greater Britain will respond. In this time period most Australians considered themselves as British first and Australian second.

The next serious issue is distance and population. The places Canada first among the dominions to respond but it would not be well into 1941 before the rest of the dominions could respond in strength with an army or divisions. So if Britton falls in 1940 we are talking about counter invasion.

All this would have a very major impact for the U.S. and its fighting of the war to come with Japan. Imagine Burma, India and the Philippians in Japanese control at the beginning of this war.

Now Russia comes into consideration will it settle the situation in the east or strike against the west. Operation Barbarossa will not happen now until at the last 42 or 43 which is when Stalin was expecting it.

The outcome of Operation Sea Lion would have had serious impact on world politics and history.

Now that part 5 is in means for my wargaming group that our background for our Home Guard campaign is complete. 😀

Good morning, @jamesevans140 –

JPK’s attitude toward the British is rather complex. A big part of why he felt the British would fold is their previous policies of appeasement. Of course what we have to remember is that he SUPPORTED this policy all through its implementation. He was definitely NOT a fan of Churchill even before he became Prime Minister, possibly because of JPK’s cherished status in London “high society” which Churchill often snubbed. There is also the possibility that Churchill, with his long heritage going back to the his ancestor the Duke of Marlboro (and perhaps earlier for all I know), looked down on JPK as “new money” or “new nobility.”

In any event, while I think we’re both big fans of FDR (warts and all) and I personally like JFK, it doesn’t sound like either of us are fans of JPK. Hell, JFK and RFK weren’t terribly big fans of his, if some of what’s come out of the Cuban Missile Crisis is to be believed.

I would agree that FDR wanted support for Britain or even American involvement in the war long before almost anyone else did. Before the Battle of Britain, though, or even the British attack on the French fleet at places like Mers el Kabir (we talk about this with Justin in the Sea Lion interview), I don’t think FDR was entirely trustworthy of Britain’s staying power. Backbone, as you say. Once this backbone was amply demonstrated, FDR is ready to start taking political risks against domestic political enemies in Congress and the isolationist public at large (while running for an unprecedented third term as US president in 1940). Once FDR wins this election, though, I think all bets are off. He gets Lend Lease through Congress I believe in March 1941.

On the actual functioning of the Commonwealth and Dominion, I’m on far less secure footing. 😀 I’m only looking at areas where there were actual instabilities or significant overt anti-British sentiment (India, which in those days included Pakistan and Bangladesh and Nepal, Iraq, Transjordan-Palestine, Egypt, etc) as potential trouble spots should Germans start landing in Kent.

Meanwhile, while I don’t think the Italians would have taken Egypt in their September 1940 invasion, their August 1940 invasion of British Somalia I don’t think would have ever been reversed by subsequent British / Commonwealth re-invasions and liberations of Italian Somalia and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). I think the Italians would have been able to hold on to these territories, and perhaps even expanded their African Empire into the Sudan (there was significant fighting here at places like Gallabat) and maybe even Kenya (some bombing, but no historical ground fighting to my knowledge).

“The places Canada first among the dominions to respond but it would not be well into 1941 before the rest of the dominions could respond in strength with an army or divisions.” – the only exception I would make here are the Canadian and New Zealand Divisions that are already in place in Great Britain in September 1940. I only mention them because the feature prominently in Part 4. 😀

All this would have a very major impact for the U.S. and its fighting of the war to come with Japan. Imagine Burma, India and the Philippines in Japanese control at the beginning of this war. Well, the Philippines are an American territory in 1941, but Burma, India, and other British possessions like Singapore present an interesting question.

I firmly believe that if Sea Lion had taken place and somehow succeeded, it would have done so through some kind of settled / negotiated peace. In these negotiations, the terms regarding disposition of the British territories and fleet become very important and very murky to predict, especially since the Tripartite Pact with Japan technically wasn’t even signed yet (September 27 1941).

If England had fallen or was in the process of falling when the Tripartite Pact negotiations were being hammered out, I’m sure Japan’s hopes to claim British territories in the Pacific would have impacted the proceedings. What would Germany have “charged” Japan for these territories? Would that “price” have fouled the treaty? Would Japan push for these territories, only to have Germany not hand them over, leaving them to Great Britain in whatever negotiated peace the Germans would HAVE to make to bring a Sea Lion invasion to some kind of successful conclusion?

I’m just thinking out loud here. There are way too many moving parts (almost none of them military) to even begin to “predict” how any of it would have shaken out.

Now Russia comes into consideration will it settle the situation in the east or strike against the west. Operation Barbarossa will not happen now until at the last 42 or 43 which is when Stalin was expecting it.

I would agree with that IF the Germans fail.

If Sea Lion is launched and succeeds, it has to do so quickly (almost by definition, the Germans HAVE to win almost any effort they embark upon within a few months). This leaves the Germans plenty of time to pivot east. In fact, the historical delays in the spring of 41 (Balkans, Greece, Crete) never happen because these were all instigated by the British, who in this timeline aren’t there.

Now, if the Germans try Sea Lion and it takes longer than a month at the outside . . . the Germans lose (again, almost by definition). Not only are they going to be late for Barbarossa, but they would have lost the better part of an Army Group in the process. In this scenario, YES, I agree my move on Russia is badly delayed, and now the Germans are really “strategically screwed.” 😀 The Soviets were in a massive rearmament and reorganization effort when the Germans hit in 1941. By 42 or 43 they wouldn’t have been 100% straightened out, but any chance at a German invasion has now passed probably forever. Any such invasion certainly wouldn’t have seen any of the initial success of the historical Barbarossa. Meanwhile, the British are still standing and a WEAKENED Germany still faces a two-front war.

I know I was supposed to set up the support thread last week. I promise (really promise this time) to get it going after Part 3 has a chance to breathe this week. I have time off coming up for our US Thanksgiving holiday, and I’ve been under the weather but I think finally feeling better and ready to “get back to work.” 😀

@oriskany I believe the politics the day is perhaps more complicated than today’s. At the least it has more layers and agendas than the present. World War is a complicated thing to begin with. Normally I try to study military history in a void without politics however the politics and strategies of 1940 do require some consideration as they are both in flux and are interdependent. I read a book called Warlords a few years ago and since then has it been made into a 4 part doco. It’s focus is on the interplay between FDR and Churchill as well as the same with Stalin and Hitler. It takes a long look motives and directions that forms policies that have to be woven into politics. This in turn drives politics that drives grand strategy. There are just a host of individuals driving their own agendas just below the big four. As for Operation Sea Lion just how Britain stands or falls appears to be a focal point that most of this rests upon.

A weaken Germany was exactly what Stalin was after for his invasion of Europe in the summer of 42/43. Let the T-34s and KV-1s roll. As we have discussed before a German invasion of Russia in 42 would have been a short lived total disaster.

Hitler when negotiating peace settlements is spiteful and vengeful. He would be insisting on pay back for stripping Germany of her colonies after WW1. Oddly even when an ally of Japan he is on record that Britain had to be kept strong in the east to preserve the balance of the region. I often wonder if he required a simultaneous east and west coast invasion of the USA.

Sorry to hear you have been under the weather and I hope your bouncing back well. It is great you have a festive break to recharge and catch up with things. Our group has been waiting the release of the supportive thread so it is great news it is on the way. 😀

@jamesevans140 –

I would normally agree about leaving politics of the day off the gaming table. And in truth, whether or not Winston is in office really doesn’t effect our Panzer Leader or Battlegroup games. I’m just including it in the narrative because I honestly feel its one of the least UN-likely paths to ultimate German victory. I certainly don’t expect them to push through the streets of London, up through the Midlands, and drive panzer spearheads all the way up into the Scottish Highlands. 🙁

I completely agree.