Gaming The American War Of Independence Part Three – The Central Theatre

April 18, 2016 by crew

To arms! To arms! We’re back to continue our wargaming explorations of the American Revolution, as presented by @oriskany and @chrisg. In Part One, we summarised the narrative motivations of the men who fought this war and some of its initial skirmishes. In Part Two, we looked at some of the first large-scale battles and campaigns.

Now we’re going to break the remainder of the American War of Independence into its three main theatres, Central, Northern, and Southern, and examine each in turn. First, we’ll look at the Central Theatre, already in full furious progress after the massive British victories in New York and the American miracle of Trenton at the end of 1776 ...

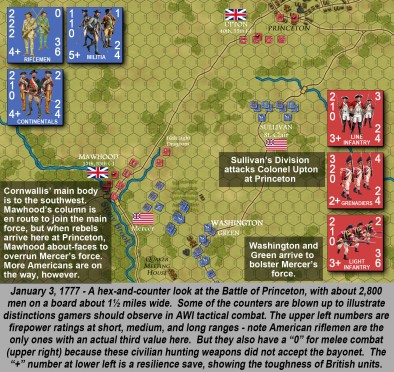

Princeton

Winning Back New Jersey

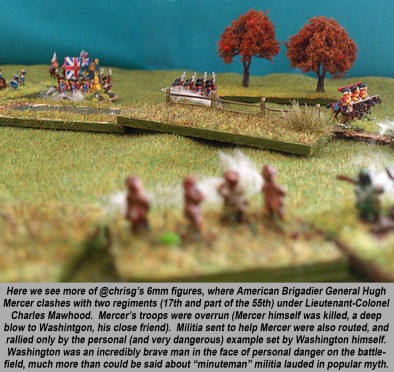

When last we left our plucky Patriot rebels, they’d pulled off a stunning upset against the Hessians at the Battle of Trenton. But now, British General Cornwallis (his return home cancelled by his boss General Howe) had been sent down into New Jersey to quash the rebel upstarts with a force approaching 10,000 of His Majesty’s soldiers.

No doubt irate over his ruined vacation, a vengeful Cornwallis soon had the rebels pinned against the Delaware River. But Washington would again pivot around the Crown’s army and hit a smaller wing of British forces at nearby Princeton, winning another victory small in military scope, but psychologically vital to the American cause.

After Princeton, Washington moved his dwindling army to winter quarters at nearby Morristown, New Jersey. This position was more or less unassailable to the forces Cornwallis had at his disposal (at least in the depth of winter), so with two small victories at Trenton and Princeton, Washington has basically won back the state of New Jersey.

Thanks to the victories at Trenton and Princeton, Washington was also able to recruit and re-enlist men into his disintegrating force. While by no means a turning of the tide, Washington’s “Ten Days at Christmas” had forestalled British victory, for now. Yet the question remained; when spring arrived, where would General Howe strike next?

Brandywine - A Patriot View

Enemy at the Gates

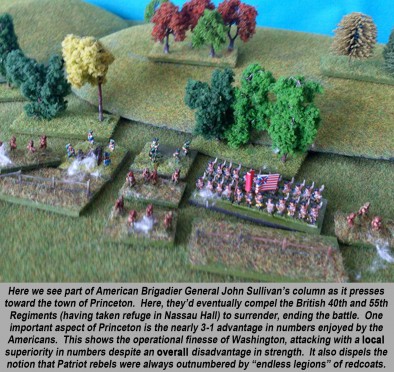

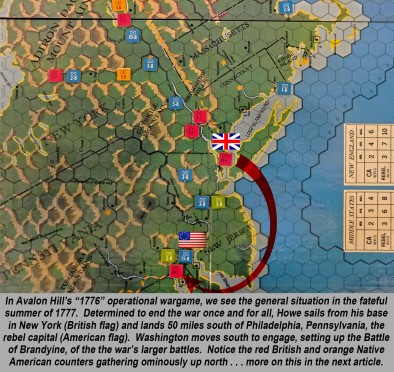

Sure enough, once the weather broke it didn’t take long for General Howe to start pushing some very big chess pieces into play. Leaving a sizeable garrison in New York City, he sailed with about 15,000 men south around New Jersey, then came up the Chesapeake Bay to land his army just fifty miles south of Philadelphia, our capital city.

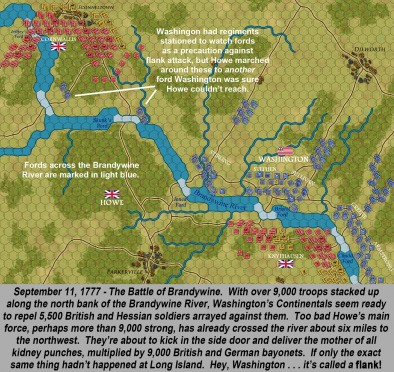

Washington, meanwhile, had spent the first half of 1777 carefully rebuilding our army. By the end of August we had about 10,000-12,000 men ready to meet Howe. To compensate for Howe’s edge in numbers, Washington set up our defence behind the Brandywine River, over which there were no bridges and only a limited number of fords.

We had no doubt as to the importance of the upcoming battle. To get to Brandywine, we first marched through Philadelphia, our capital city which would now be our honour and duty to defend. Members of the Continental Congress, the very men who’d written and signed our Declaration of Independence, waved as we marched by.

Sure enough, the British and their bought-and-paid-for Hessian mercenaries lined up in their pretty lines of red, blue, and gold, marching right at us. We knew we had to put up a good fight because a young French general, the Marquis de Lafayette, was with us. If France was to join the war on our side, we had to prove we could fight.

And fight we did. Soon, however, we heard gunfire thickening in the woods to our right. Then came the first panicked reports of a massive force on our flank. We’d only been fighting a third of the enemy force! Their main body had somehow crossed the river without our knowledge and were about to cave in our whole right wing!

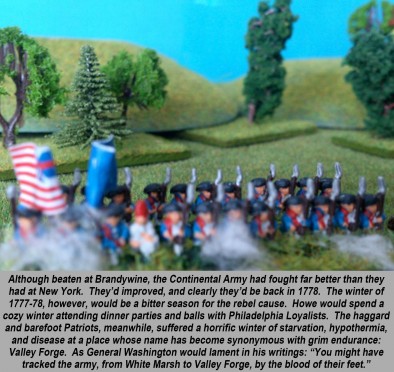

Yes, we lost. We lost the field, over a thousand men, and with them our capital city. At least the Congress had escaped … and our army remained intact. Unlike New York, we hadn’t disintegrated in defeat. We’d be striking back, and a damned sight sooner than our friend Mr. Howe likely expected.

Brandywine - The Crown View

“This war SHOULD be over.”

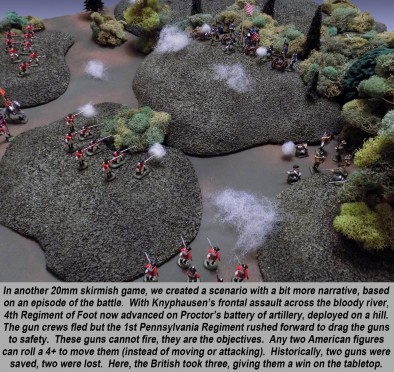

I would have paid twenty pounds sterling silver to see the look on Washington’s face when he was informed we’d flanked his army... again. With Knyphausen demonstrating against the rebels’ front at Chadd’s Ford, we’d force-marched around their right wing and now stood ready to bag the lot of them.

Three hastily deployed divisions of rebels, however, made a passable account of themselves, and stalled our advance long enough for the bulk of the rebel force to make an orderly withdrawal. We took the field and plenty of prisoners, but I must confess these rebels are slowly learning how to put up the semblance of an actual fight.

Not that we were done thrashing these ungrateful wretches. Moving on their capital at Philadelphia, we eliminated another rebel force at the Battle of Paoli (September 20th), which of course their propagandists choose to characterize as a massacre. Finally we marched into Philadelphia itself, capturing the city on September 26th.

Still the rebels hadn’t had enough, Washington attacked one of our outposts at nearby Germantown on October 4. After being outflanked at Long Island and Brandywine, Washington now outflanked HIMSELF by turning part of his army the wrong way to attack a bypassed mansion. The rebels lost yet again, ending the year’s campaign.

Yet how did the war NOT END HERE? We’d taken the enemy’s capital, we’d defeated his field army … twice. In any traditional terms, this game was well and truly up. But these rebels don’t abide by any civilised rules of honour or warfare. They simply scampered into the woods like so many deer, and so we’d have to beat them again in 1778.

Monmouth

The Revolution’s Largest Battle

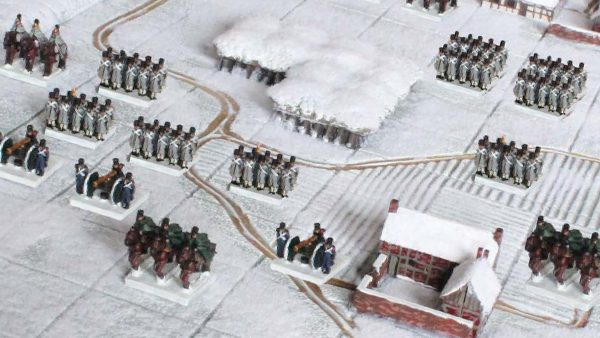

After a harsh winter camped at Valley Forge, spring brought two great boosts to American morale. First, Baron von Steuben, a Prussian drillmaster, had brought much-needed professionalism to the Continental regiments. This reflects in AWI gaming since, starting in 1778, the Americans start to look and act like an actual 18th Century army.

Second, France had finally joined the war on the American side. This caused an immediate shift in British strategic priorities since troops, ships, and money would be needed to meet French threats against rich British possessions in the Caribbean and elsewhere. These colonies were incredibly wealthy, far more valuable than Philadelphia.

Accordingly, British forces in North America would have to be significantly cut back. The new British commander in America, General Sir Henry Clinton, was forced to abandon Philadelphia and consolidate Crown forces back to New York (General Howe had stepped down, unhappy with how the war was being run from London).

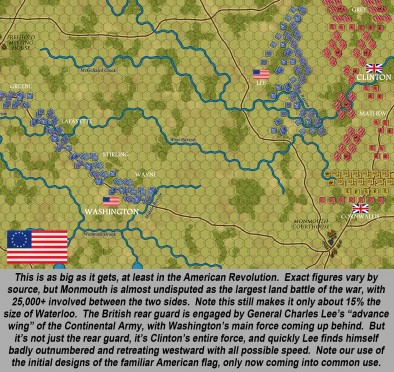

Accordingly, General Clinton massed his army in Philadelphia and started a march northward to New York. The column was huge, an opportunity Washington just couldn’t pass up. He attacked Clinton’s withdrawing army near the town of Monmouth, New Jersey, starting what is widely regarded as the largest single battle of the war.

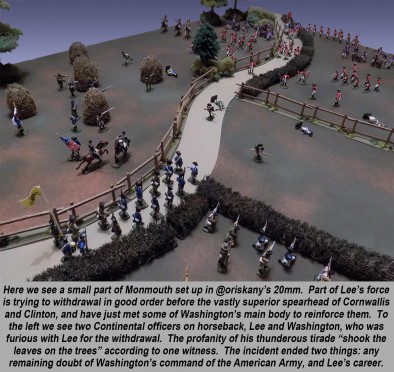

The American vanguard was commanded by Charles Lee, hateful and jealous of Washington’s position, but nevertheless a competent general. He hit what he thought was Clinton’s rear guard north of Monmouth Courthouse, but the whole Crown army swung around and quickly pushed back Lee’s outnumbered forces.

When the rest of the Continental Army met Lee’s withdrawing vanguard, Washington demanded to know why Lee had pulled back. Deaf to excuses, Washington relieved him on the spot … in a screaming barrage of profanity, no less. Simply put, Washington had had enough of Lee’s scheming, insubordination, and now alleged cowardice.

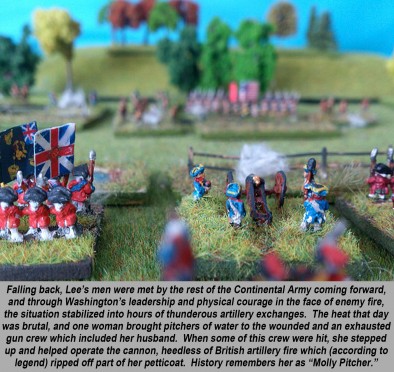

Taking command of Lee’s forces himself, Washington stabilized the field as the two armies locked in an artillery duel that lasted hours (the American guns in enfilade positions on Comb’s Hill). In the end, the battle was a draw. But for the first time, the Americans had met the British face-to-face in a large, formal battle, and had held the field.

After Monmouth, Clinton completed his march to New York. There would be no more major battles fought in New Jersey, New York, or Pennsylvania. Effectively, the central theatre was closed because, as we’ve discussed, the war’s centre of gravity had been irrevocably shifted by France’s entry into the war.

Without France, American success in the Revolution would never have been possible. Yet France would’ve never joined until America proved its viability with a decisive victory in a major battle. As it happens, just such a victory had recently been won in the Revolution’s northern theatre, in one of America’s most crucial turning points …

… near a small New York town, called Saratoga.

By James Johnson & Chris Goddard

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"...while by no means a turning of the tide, Washington’s “Ten Days at Christmas” had forestalled British victory, for now. Yet the question remained; when spring arrived, where would General Howe strike next?"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Without France, American success in the Revolution would never have been possible. Yet France would’ve never joined until America proved its viability with a decisive victory in a major battle..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Well done sir. AWI is one of those projects I have always wanted to do but never seem to find the time. I have a few skirmish forces and used some of the Canadian war gaming group rules but that is as far as I have gotten. I have picked up Black Powder and Musket and Tomahawk as well. One of the members of our group has a large collection of forces for AWI already which is one of my excuses for not doing more. Not to mention all of the other shiny stuff 🙂

Thanks very much, @tibour – I certainly know where you’re coming from, getting started in the AWI entails a lot of work up front. Speaking only for myself, it was painting all that infantry. Typically I’m a WW2 / Moderns guy, and when trying a new system I have always had some vehicles, terrain, and infantry I could repurpose or at least use as a base for a new army. This Revolution stuff I had to build up from scratch . . .

. . . and of course I wanted a lot of it, because more is more!

Another epic installment in the series, guys. Amazing how close “we” actually came to losing this war. It’s also great to see how much help we got from other countries. 🙂

Thanks, @gladesrunner ! 😀

The rebels were not learning from mistakes seems to be the order of the day?

Well actually no, lets not under play the fact is the mildly named rebels are facing seasoned generals in a professional army.

The army of the British empire of the day were professional, they were not merely a payed group of armed men (mercenaries), they were also (other than the soldiers present who had the choice of prison, deportation or their choice the army) volunteers. They were well drilled and used to winning the british empire was not made on being polite or politically correct. Dealing in trade with Great Britain was often a matter of “we will” do trade with you, when you rule the waves and have large armies at hand.

So although we today do not have the gift of time travel (I wish! I have been married three times now) I wonder what the morale of any force facing off against lined infantry dressed in red coats belonging to the largest historic empire ever, an army that you know well is a winner. This army is the same army you fought alongside in the French Indian wars, (which is why their there in the first place and the paying for is what is causing the taxes you the rebels don’t want to so now your having to fight, er sorry run away from.) They don’t make a noise except the officers and sergeants shouting orders (very eery indeed). They fill their front rank as they suffer casualties, then worse of all they fix bayonets and then they make a noise as they close and stab the enemy to death. The British army even practiced bayonet technique in such a way that they fight often not the man to their front but the man to their left. So outflanked yes, out classed yes, out of real guts and glory NO! The finnish have a word “sissu” it’s how they beat the Russian’s out numbered by them, out gunned and possibly an over confident army. The British army up to this point had done nothing but chase the Americans tails.

The British it has to be said and given the above had not been tried, but as we have left the fighting in the American colonies there is a huge shock waiting in the wings awaiting its queue.

Then we the British have to remember how many countries we had recently alienated in European countries as well as the American and Canadian colonies.

Had the war in America been lay’d down by the Generals in the field something else that may come as a surprise to many, the revolution may well have failed completely or better said throttled and stamped into the dust.

On a personal note I want to again say thanks to Oriskany for putting my gibberish into readable gibberish. LOL

Thanks, @chrisg – I have to agree with about 95% of what you say in your post. The British army (both officer corps and rank-and-file) were far more professional than that of the Patriots, especially in this part of the war. Sure, there were problems among the enlisted men with desertion, jail-dodgers … and with the officers there were those who simply bought or inherited their commissions. But even with these drawbacks, the British were stacked far and above the quality of their opponents.

As far as the quality of generals go, again the better overall marks go to the British. But the issue gets a little more complicated than that. Washington, to use a quick example, is one of the rare birds in military history who is terrible at low-level, tactical combat, but is a borderline genius operationally. Tactically he is a borderline buffoon – he gets outflanked at Brandywine, he gets outflanked twice at Long Island, and Germantown he outflanks himself. The only battles he really wins are where he outnumbers his enemy 3-1 and has total surprise. Operationally, however, he does much better, the only real operational blunders he makes (defending New York against Howe in 1776), are forced upon him by Congress. His writings before the battle show they he KNEW he was walking into disaster. But his bivouac at Morristown, holding the Lower Hudson against Clinton in 1777-79 despite the loss of Forts Washington and Lee (and the near loss of West Point, thanks Benedict Arnold 🙁 ), and his cooperation with the French leading up to Yorktown, all how he’s much better at the higher-level chess game than fist-fighting down in the musket smoke.

This is an oddity in history, of course. History is littered with crap generals who were great colonels, amazing division commanders who were given a corps or an army and fell apart. Usually when a commander is bad at a lower level of command, he’s either killed, relieved, captured, retired … somehow his career comes to a quick and merciful end. Washington was a terrible tactician (as shown back in the French and Indian War) but by a trick of fate, is given a chance at higher command anyway, at which he excels. Thankfully, he had some great tactical subordinates (Benedict Arnold, Nathaniel Greene), who were able to mitigate his shortcomings on the actual battlefield.

The British seem to have the opposite problem. Tactically their generals (especially Howe and Cornwallis) are genius, battles like Long Island, Brandywine, Savannah, Charleston, Kips Bay, White Plains, Fort Washington, Fort Lee, are all masterpieces. But time and again Howe lets the rebels escape when another HALF HOUR of combat would have probably ended the war. Cornwallis wins basically every battle in South and North Carolina but in the end his army is ruined. Cornwallis fails to finish off the Americans between Trenton and Princeton. Burgoyne has a great plan to take New York and split the colonies but forgets that there is NO ROUTE through New York between Lake Champlain and the Hudson, or even to make sure Howe will come up the Hudson to meet him (instead of heading south to beat Washington before Philadelphia).

I will totally agree that the British Bayonet was the most feared weapon in the war, perhaps even more so than the American rifle, the French Navy, or the Dutch bank account. 🙂 That is baked into the hex-and-counter game, where British line infantry and grenadiers have “3” melee value, the American Continentals usually have a 1 or a 2 for “elite” regiments. Perhaps even more importantly, the British grenadier companies save on a 3+, the Americans on a 4+ or 5+ for militia. Playtesting has shown that if the British can hold together through American musketry and rifle fire, once they get to bayonet range, that’s all she wrote.

A lot more on this later, especially the cooperation and assistance from other nations.

Annother excellent installment guys, really enjoying becoming less ignorant on the topic 🙂

Thanks very much, @nakchak . Hope you had a great time at Salute! 😀

Me too. This is a subject that was never mentioned in history lessons at school. Nice and informative stuff.

After your many examples I might be tempted towards these style of hex-based games. Some really stunning gaming examples and pictures – as always.

I might not ever game this war, but I am now tempted to at least read something about it. Nice one.

It’s an acquired taste, to be sure. AWI will never fully replace WW2 or Moderns as my “go to gaming” setting, but it’s a welcome break, a refreshing change, and a wholly different “geometry model” from the “diesel fuel” wars of later years. 😀

I’ve never considered getting into hex-and-counter games until this series. Now I’m thinking AWI or ACW would be a great starting point.

Thanks very much, @rfernandz2001 – The thing about hex-and-counter games is that their “level of investment” is much lower than spending money on a large miniatures force, weeks to paint it, then find and learn a new system, etc. etc. With hex-and-counter games, you can get started within minutes (or hours at the most, if it’s a real big game or complex system), and get an idea whether you really like the era / genre / conflict / etc.

Also, hex and counter games allow you to simulate much larger battles. The big one of Monmouth (and trust me, that one damned near broke the system, and took about 6 hours to play) would have required 25,000 miniatures and a table almost 200 feet across to do in true 20mm 1/72. Granted, it would have looked awesome … you you seethe dilemma. 😀

The only real pain in hex-and-counter games for AWI or ACW is the need for custom maps. Each battle needs to have its own map. Other hex-and-counter tactical games for, say … World War 2 usually have modular boards you can use over and over again in different configurations. I’m sure the same solution would work for AWI / ACW, but the historical accuracy of your battlefield wouldn’t be as sharp.

As an aside are Strategy & Tactics and Command magazine still going?. They used to have some nice little games in them

There is a thing on Scribt that has them all…

I am subscribed to “Strategy and Tactics”, plus their two magazines “World at War” (same thing but focused exclusively on World War 2) and “Modern War” for post 1945 wars, conflicts, scenarios, and games.

In fact, there are 3 issues sitting at home right now waiting to be read. 😀

Yes, you’re right, @torros , a new game in practically every issue. Their “Folio” series is particularly good, especially for those just getting started in a new ‘genre.’

I wonder if the games from the magazines are on vassal

Doesn’t really look like it, just checking on Decision Games’ website (the publishers of the Folio Series). They do have some PC-based versions of their games, to include internet-capable PvP options. 😀

These are the guys who make the truly MONSTER hex-and-counter games, the kind that send even me screaming into the hills. 😀 I think that’s the point of the Folio series, to give new players a gateway, and to give veterans a break from their really big games.

I’m impressed with the idea too. No idea what I would play though.

The great thing about hex and counter games is that there are some options for long-distance play, allowing people from different countries or continents to get together and run games or campaigns. 😀

Great stuff full feedback to come

Thanks very much, @rasmus, appreciate it!

Looking forward to the next installment. I live not at all far from Brooklyn Heights and Saritoga is just a short drive up the Hudson valley. If I ever get around to AWI I’ll be doing my forces for the Saritoga campaign. I hear they even had special hats!

@koraski – Saratoga and the northern campaign of 1777 is my favorite part of the while conflict. We cover it in Part 04 (next week), so we hope you like it!

another great read guys a lot of twists & turns in this war brilliant all the same.

Thanks very much, @zorg ! Glad you like it!

@koraski I can’t tell exactly where in the Hudson Valley you live, but if you can get there, West Point (the United States Military Academy) is worth visiting for several reasons.

The first is the restored Fort Putnam which was a major part of the fortifications there. When we did staff walks with the cadets I liked to ask them how they planned to handle the mechanics of 3-400 men cooped up in that small a space – sanitation, hospital, and so on.

The second is the north side of the parade ground where they have a link from the original chain that ran across the Hudson. The view is spectacular there and you can clearly see why West Point was such a critical location.

The third would be the museum there that is a teaching museum. There’s lots of cool stuff you can spend hours looking at.

@mwcannon I live on Long Island. I was born just a few miles from Brooklyn Heights, across the border in Queens. I’ve never had the opportunity to visit West Point. I thought it was a school so wouldn’t have occurred to me to go there!

Visited West Point about 35 years ago, I think I was 9-10. I remember some amazing museums and dioramas.

Looking at a map (and I’m sure you know this, @mwcannon , but for others who might read …), we see where the Hudson forms something of an “S” shape there at West Point. Ships of the 1700s couldn’t sail through there, they’d have to stop, lower long boats, and literally be towed around this spot. This is how the chain would stop shipping from moving up and down the river. Ships couldn’t simply break through the chain (it was a big-ass chain, for those whop might not know), and even if the chain only slowed down the enemy ship, batteries on both riverbanks could shell the ship into flaming splinters at point-blank range.

With no fords or bridges in those days, the Hudson would have completely bisected the Colonies if the British Navy could get ships past these forts. Of course the Americans had no ships to contest them, these forts were the only way the Americans could deny control of the Hudson to the British and keep transport and communication across the upper Hudson open.

You have to think your way through it, but keeping in mind the limitations of the day, you can see where a single strategic, well-chosen, and fortified point (under the right conditions) can actually control movement and campaigns for hundreds of miles around.

another great instalment!! think you’ve really got it right with this series so far, balanced, broad in scope – looking forward to the next as always 🙂

Thanks very much, @bigdave .

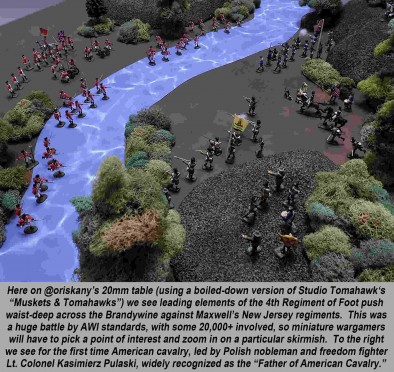

One part of the balance we haven’t had much room so so far is the cast of figures, leaders, and commanders that joined the Revolution from other countries. Of course we all know the Marquis de Lafayette from France, who (as a 19-year old major-general) saw his first battle, suffered his first defeat, and took his first bullet at Brandywine (discussed in the article), September 11, 1777.

Also there will be Casimir Pulaski (“Father of American Cavalry”) and Tadeusz Kosciuszko (“Father of American Army Engineers”) and of course Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, mentioned at the beginning of the Monmouth section. This was the Prussian officer who’d basically been forced out of the Prussian Army, so came to American in an attempt to continue his career. Whatever his shortcomings, he helped train, drill, and mold the American army to some degree of professional status, to where it could stand and face trained British regulars in open field.

There’s a funny story, written down by one of von Steuben’s aides:

“When some movement or maneuver was not performed to his liking, he would start to swear in French, then swear in German, then swear in both languages together! When he had exhausted his artillery of foreign oath, he would call one of us over and say:

Come and swear for me in English! These fellows won’t do as I bid them!”

Entertaining and informative as always, gentlemen. As a Canadian, it’s hard to know where to come down on this conflict…. absolutely loyal to the Crown, but sympathetic to the American cause.

I am , however, loyal to my friends on both sides of the pond, so that may be enough 😉

Again, brilliant work! 🙂

Thanks, @cpauls1 . Fortunately, this conflict is 240 years behind us, so the embers have cooled sufficiently to allow calm, reasoned, balanced, and objective discussion of the topic …

… usually. 😀

Brilliant series so far. Could I recommend the Revolutions podcast by Mike Duncan, I’ve found it great for a reasonably in depth overview of the political situation. Especially coming to the period relatively clueless.

Thanks, @rovens – I’ll look that up and check it out! 😀

@oriskany The importance of the Hudson cannot be understated. That’s one of the reasons why wecame so close to disaster when Benedict Arnold turned coat.

And those chain segments are about the size of a volkswagen, they must have been a nightmare to put together and chain across the river.

Those links are definitely huge, @mwcannon . From what I remember, they took the chain down every year when the river froze, and stretched it from one fortified cove to the other again in the spring.

And yes, I’m kind of an “apologist” (certainly not a “fan”) for Benedict Arnold … as may become apparent in Part 04. But I certainly can’t stand up for his betrayal or how he nearly gave away West Point to the British (and in so doing, would have split the American colonies practically in half).

Poor form, Benedict. Very poor form. 🙁

Never been to West Point, but we did take a trip up to Saratoga one time. I think they call it Schuylerville now? Saratoga Springs? More famous for horses now than battlefields. It was a great trip, very nice up there, even if it was the middle of March! Brrr!

Yeah, not the best of timing on that trip. 🙁 I had some writing on Saratoga and wanted to walk the actual battlefield at Saratoga National Historical Park ( https://www.nps.gov/sara/index.htm ) – yes, it was the middle of March, but we had some great weather. At one point, though, yes, I was tromping around the field in horizontal sleet. 😀 Totally worth it, though.

Great stuff @oriskany and @chrisg

It is nice that you remarked on Pulaski. Thumbs up.

Man, you really had to respect winter during warfare back then (not that you don’t have to now).

Thanks very much, @yavasa ! Indeed, Casimir Pulaski is widely recognized as the “Father of American Cavalry” – so all you guys who love playing Hueys, Cobras, and Apache gunships in Team Yankee, that line starts here with this man 1777-79.

I know a lot less about his fighting and accomplishment in Poland (“Bar Confederacy?” – do you know anything about this?)

Sadly, he went down during the disastrous Franco-American siege of Savannah, hit by British grapeshot from artillery. I used to be stationed right around there.

He didn’t see as much combat, but Tadeusz Kosciuszko designed / built a lot of the forts in New York (including West Point) that protected the Hudson we’ve been talking a lot about.

I think he was ethnically Polish or Lithuanian (or both), but when I look it up I find that his birthplace actually now lies in Belarus.

@oriskany Well Pulaski had seen a lot of fighting in Poland during the Bar Confederacy as you have pointed out. Actually it would be a really long story but to keep it short let’s just say that the Commonwealth (Poland, Lithuania) was a really weak entity at that time with Prussia, Russia and Austria heavily influencing the politics of the king and the Sejm (so to say a kind of Congress you see in America). Basically the Bar Confederation was against Catherine II of Russia influence on the internal and foreign affairs of the Commonwealth and king Stanisław II Augustus who was trying with a group of reformers limit the power of magnats (the richest and most influential nobility members). Plus there was a religious reason. Prussia and Russia wanted to give, and gave, with the help of 40 thousand Russian troops, full rights to non-catholics in the Commonwealth. Please take note, that it was a really innovative move at that time and not well seen by the nobility which was mostly catholic. Yet, the king and the Sejm forced by the Russian soldiers presence and the influence of Catherine agreed. Then the Bar Confederacy started in 1768. He was one of the top commanders despite being only 23 years old at that time. He defended a small fortified monastery at Berdyczów for two weeks. Next he defended an old and useless fort of the so called (my translation) Holy Trinity Trenches for three hours against the Russians. He defeated Russian under the command of Jelczaninow at Iwla and then went on a cavalry ride to Lithuania where he managed to breakthrough from being surrounded by Suworow at Łomazy. After being wounded in 1769 he managed to start an anti Russian uprising in Lithuania and Rus (part of Ukraine now under Putin’s puppet states now). He also defended Jasna Góra monastery from the king’s and Russian forces led by Drewicz for a few weeks during 1770/1771. Well he even made a failed attempt to kidnap Stanisław II Augustus. All in all, the confederacy failed and Pulaski was sentenced to death but he luckily managed to emigrate with a lot of the confederates. Many were not so lucky and were sent to Siberia. Soon after the First Partition of the Commonwealth took place. Pulaski then joined the American Revolution. 🙂 As far as I remember it was Benjamin Franklin who presented Pulaski to Washington.

I am not sure whether Kosciuszko was Lithuanian/Polish but yes Merowszczyzna were he was born now lies in Belarus. During the 1921-1939 it was a part of Polesie. In 1945 some parts of Polesie went to Belarus and some to Ukraine. This place was a real melting pot throughout the ages.

Holy crap, what an awesome post @yavasa ! Better watch out, people are gonna be asking you to present an article series on this material. 😀

From what I can find, yes, Pulaski met Benjamin Franklin in France, where Franklin had been trying for over a year to get the court of Louis XVI to put French troops, naval power, and especially money into the AWI on the Patriot side. So far he’d been stuck, because France was wary of jumping into another war against Britain (they’d been ruinously defeated in the recent Seven Years War). It wouldn’t be until the First and Second Battles of Freeman’s Far (Saratoga – Sept / Oct 1777) that America would have a sufficiently viable victory to facilitate France’s entry (March 1778).

Meanwhile, Franklin did his best to send whatever help he could America’s way from Europe. Loans, arms smuggling contacts, and qualified officers, one of which was Pulaski.

Pulaski lands in Boston in July 1777 and reports to Washington. His commission hasn’t even come through yet when he’s right next to Washington at the Battle of Brandywine (discussed in the article, Sept 11, 1777 … America’s just never had good luck on September 11, it seems 🙁 ).

Pulaski riding right next to Washington is important. When Major Ferguson aims his rifle, designed and built himself, at “a prominent American officer,” he also describes another officer riding beside him. Ferguson decides not to fire and “assassinate” the man. Based on where he was and the time of day, AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE MAN BESIDE HIM, historians are 99% sure Ferguson had Washington himself in his sights and could have killed him outright then and there (not sure, but perhaps Pulaski had a distinctive uniform, which made this identification easier?)

As the American army was beaten and started to retreat, Pulaski asked for and was granted permission by Washington to lead his 30-man cavalry detachment on spoiling attacks, first on the British center and then their flank. These slowed the British advance long enough to allow portions of the American army to escape.

30 men … against Howe’s army which totaled 13,000 … twice. Granted, all 13,000 weren’t at that exact spot, but the point stands. All this from an officer who’s commission hadn’t come through yet (i.e., he hadn’t “officially been hired”).

That’s a grade-A badass in my book. 😀

Thanks again for the great post.

Thank you for the kind words @oriskany and thank you and @chrisg for this wonderful series of articles.

No worries, @yavasa , we love doing them. Three down, two more to go! 😀

Another good instalment @chrisg and @oriskany. So refreshing to see the myth separated from the fact.

I think Washington was aware of the concept of the flank it is that he continually demonstrates a lack of the notion of flank security. They also seemed to forget if you grab a snake by the tail it is only going to swing around and bite you.

During the musket period the taking of cannon was part of victory and often it was a count of who captured the most guns. This would be a causing element in the next century for the infamous charge of the Light Brigade.

I read a paper a while back that looked at the British performance in the continental temperate south and came to some interesting conclusions. The British uniform had developed on the battlefield and addressed the needs required of it in Europe. It was too heavy and did not breath well enough for the high humidity combined with temperatures encountered at Monmouth. Heat stroke and exhaustion was an issue for the British, their own uniforms were fighting for the US. The humid heat may have fuelled Washington’s outburst.

Concerning French involvement I always draw a parallel with Roosevelt testing the British stomach for war when he was considering an alliance.

One often overlooked skill required by senior command is they must know how to fight a war and just as importantly they need to know how to finish one. The Germans in 1940 and Hannibal showed a lack of this all important skill as well as British command in the US.

Thanks very much, @jamesevans140 –

I think Washington’s great skill at some “levels of wargaming” and poor clumsiness at others (i.e., flanks on the tactical field) is pretty common. It’s just weird that he’s bad at the lower tactical levels yet great at the bigger operational levels. usually when you’re that bad at something, you don’t get a chance at the levels with more responsibility.

I mean can you picture that at a job site or office job? “Phew, this guy STINKS at this! Let’s promote him and see if he does any better with more responsibility.” 😀

It’s pretty unusual that a general is great at all levels. Napoleon comes to mind. Simultaneously he’d act as the Emperor deciding which country to attack next (strategic), then he was the Marshal on campaign (operational) and when the armies finally closed for combat, he was usually still in command on the battlefield (tactical).

Absolutely agree on taking of cannons, which may have been even more important for the early American patriots since they had no facilities to build cannon (or European countries yet willing to smuggle them arms and money … hey, why is Holland suddenly slinking to the back of the room?) Hell, that was the whole point of the seizure of Fort Ticonderoga, we needed big guns.

Conversely, the British would often find their guns were practically useless. The range of good American riflemen was actually longer than light- and mid-gauge battlefield artillery (4-6 pounders) in those days. Very quickly the riflemen were used to shoot down the crews of British artillery crews standing in the open (e.g., that bloody afternoon at First Freeman’s Farm, Sept 17, 1777).

The heat was definitely a factor at Monmouth. Both sides reported fatalities from heat stroke. I would certainly assume the heavy British uniforms weren’t helping. Ironically, this was the same American Army that had just lost 2500 men to frostbite and hypthermia at Valley Forge the previous winter. Too hot, too cold, those guys couldn’t buy a break.

I would certainly agree that those uniforms didn’t help in the south, either. I LIVE here, remember … 😀 and usually it’s too hot with jeans and a t-shirt. I can’t image marching 20 miles a day in wool uniforms, leather boots, and 70 pounds of kit. Maybe this was why so many of the battles took place in the fall and winter? (Okay, except for battle of Camden on August 16), which the British WIN decisively)?

Hey, you don’t have to tell ME how important it is to finish a war! 😀 I’m an AMERICAN, we’re awesome at finishing wars! Look how quickly we wrapped up that whole Iraq thing, and Afghanistan, too! I mean, wait … ehh … what were we talking about again? 😀