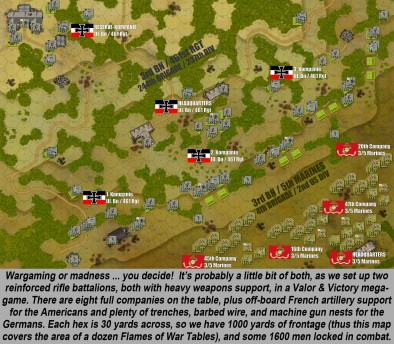

Centennial Gaming In The Great War – The Campaigns Of 1918: Part Four

May 14, 2018 by oriskany

We’re back once again for another look at centennial gaming in the Great War. Through the course of this series, my friend Sven Desmet (BoW: @neves1789) and I are putting a “tabletop focus” on the spring and summer battles of 1918 – engagements that shaped how World War One would end, and how the 20th Century would unfold.

Read The Series Here

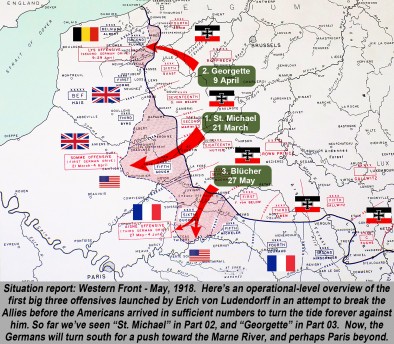

So far we’ve looked at wargaming in the Great War in general, the St. Michael Offensive of March-April 1918, and the Fourth Battle of Ypres in April and May 1918. Combined, these offensives represent a determined German effort to win the war on the Western Front before new American forces could arrive in decisive quantities.

These German pushes had, for the first time since 1914, put much of the Western Front in motion. The St. Michael Offensive had caved in the British front at the Somme, while subsequent offensives like the “Georgette Offensive” (April 9th) had hit the line in Flanders, sometimes held by French, Belgian, Australian, and even Portuguese troops.

As we saw in Parts Two and Three, the Allies were hideously mauled by these attacks, especially the British. Nonetheless, they managed to prevent a German breakthrough toward Amiens, from which the Germans could threaten British access to the Channel ports and destabilize the whole northern half of the Allied line. Amiens had to hold.

Hold it did, with the Germans stopped at a small town called Villers-Bretonneux, which changed hands repeatedly in a series of bitter battles. French reinforcements were poured into these threatened sectors, while further north in Flanders the line also began to stabilize after the Battle of Lys.

The Blücher Offensive

The Germans Turn South

It was these French reinforcements that concerned the German commander, Erich Ludendorff. Quickly he whipped up what was supposed to be a diversionary attack further south, with his First and Seventh Armies driving between the cities of Soissons and Reims, aiming at the Chemin des Dames region along the Aisne River east of Paris.

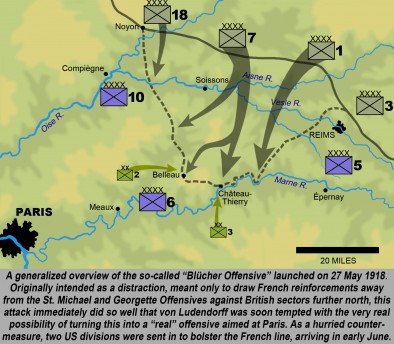

This would be the “Blücher Offensive,” which opened against the French Sixth Army on May 27th. The objective was to rattle the French and draw French reinforcements away from the threatened British and Belgian sectors further north. Then, new German attacks could build on what “Michael” and “Georgette” had already achieved.

But the Blücher Offensive was stunningly successful beyond even the wildest German expectations. Two French divisions (21st and 22nd) were all but annihilated were they stood. German stormtroopers and follow-on infantry crossed Aisne River and pushed all the way to the Marne River, now within potential striking distance of Paris.

Ludendorff had a decision to make. Should he exploit this unexpected success, or stick with his original plan? The road to Paris seemed all but open. When the French Prime Minister asked the commander of the French Sixth Army what remained to stop the Germans, he replied “nothing but dust.”

The overall French commander (and C-in-C of Allied armies), Généralissime Ferdinand Foch, was surprisingly unconcerned. He maintained that so long as the width of the German breakthrough could be contained, they would be unable to exploit it beyond a critical point.

In this, Foch was actually correct, but the fact remained that German armies were barely forty miles of Paris. The city was under German artillery fire, and practically nothing stood in their way. Finally, the French urged the Americans (commanded by General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing) to send in some of his newly-arriving American divisions.

This was actually a bit of a risk. Debate still simmered between Allied generals as to how the new American divisions would be used, where would they deploy, and who would actually command them. Would they be attached as reinforcements to British and French armies? Or fight on their own as an integral American force?

Such questions would have to wait. For now, the US 3rd Division was shoved into the line along the Marne River…just in time. They halted the German advance at Château-Thierry in a rather bloody repulse as the Germans tried to cross a railroad bridge over the river. For the immediate present, a further crisis was averted.

Shaking off the bloody nose, the Germans shifted their next big attack eight miles to the west. Now even closer to Paris, they began a push toward wooded hills around the town of Belleau in preparation for yet another try at cracking the French line, reinforced by more American infantry, this time of the US 2nd Division.

Yet not all the Americans on the imminent “Belleau Wood” battlefield were technically US Army troops. The 2nd Division included the 4th Brigade of the US Marine Corps, including 5th and 6th Marine Regiments. It was for these Marines that Belleau Wood would become much more than a battle. For United States Marines, to this very day…

…Belleau Wood is legend.

Battle Of Belleau Wood

Making Of A Legend

In the opening days of June, German General von Conta’s IV Reserve Corps (Seventh Army) resumed their southwest advance. Two of his divisions, the 197th and 237th, pushed toward Belleau Wood, steadily driving against the rapidly-splintering French. The US 2nd Division, still arriving, tried to deploy a new defensive line amidst the confusion.

The French tried one more counterattack on June 3rd, which quickly broke down. As the remnants of their 164th Division fell back past the American positions, their officers approached the Americans of 2nd Battalion / 5th Marine Regiment with news of a general withdrawal. A Marine company commander entered legend with the reply...

“Retreat, hell! We just got here!”

Just a quick footnote, sharp-eyed readers may note that this is the same 2nd / 5th Marines featured so prominently in our recent Vietnam Tet Offensive series, particularly at the Battle of Hue in January and February 1968.

Such bravado would soon be put to the test. For the next two days, the US 2nd Division, Army and Marines alike, would see off repeated German attacks trying to come down off the heights of Belleau Wood. Particularly fierce fighting would come at Les Marnes Farm, the precise closest point the Germans would ever come to Paris in 1918.

But the Germans could push no further. Soon two new French divisions arrived, the 167th to the north and the 34th to the south, to bolster the embattled Americans. More fighting came at Les Marnes Farm, where Germans of the Saxon 26th Jäger Regiment recovered an American body and finally realized they were up against US Marines.

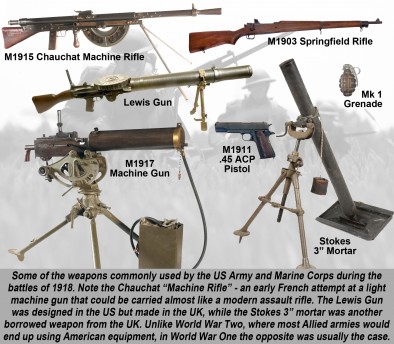

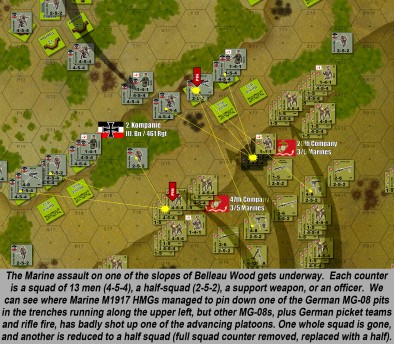

On June 6th the Allies went over on the offensive. The French 167th would launch the main assault, with the Marines supporting on the right. The objective was Hill 142. Yet the Americans were overconfident from their defensive successes. The didn’t conduct good field reconnaissance and definitely weren’t practised in modern assault tactics.

The Marines advanced in neat lines, with bayonets fixed, over open fields of tall wheat strewn with red poppies. One NCO, Gunnery Sergeant Dan Daly (who’d already won the Medal of Honor is previous wars), gave the famous cry...

“Come on, you sons of bitches! You want to live forever?”

Sure enough, German machine gunners had a field day, and casualties were horrific. The Marines would take a foothold in Belleau Wood but at a shockingly grim cost. At least one company commander was killed instantly, and another NCO would win the first Marine Medal of Honor in World War One, fighting off German counterattacks.

Over the next few days, the Germans struck back at the new American positions, but to no avail. Again, the Battle of Belleau Wood was in deadlock.

Over the next two weeks, the Americans and Germans would trade ferocious attacks, followed by counterattacks, followed by counter-counterattacks. German and French artillery ravaged the beautiful hunting preserve, turning Belleau Wood into a surreal tangle of smoking, splintered trees. June 10th through to the 15th would see the heaviest fighting.

The Germans were grimly determined, dug in, and no stranger to battlefields of the Great War. Beyond the Marine, Army, and French lines, they thought they could see the road to Paris and maybe even an end to the war…and fought accordingly.

The Marines, meanwhile, were not as experienced, sometimes even attacking in the wrong direction after losing their bearings in the smouldering, misty woods. But they smashed any position they hit, often with bayonets, rocks, or bare hands, fighting with a ferocity that diaries and letters home prove genuinely unsettled the German veterans.

Finally, on June 26th, 3rd/5th Marines cleared the last of Belleau Wood. Without this covered high ground anchoring their lines, the overall position of the German IV Corps became untenable and a slow withdraw was soon underway.

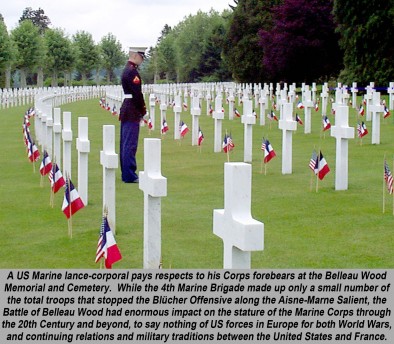

Of course, the Marines played only a small numerical part on the overall battle. The 4th Marine Brigade was only part of US 2nd Division. Meanwhile, the rest of US 2nd, along with the US 3rd Division, plus several French divisions, all paid steep losses and contributed greatly to the final result.

But the Marines had made an indelible impression on the European battlefield. The Germans reported they fought like “dogs from Hell.” Whether the exact term was “Höllenhunde” (hounds of Hell) or “Teufelshunde” (devil dogs) – the sobriquet “Devil Dog” is carried with fierce pride by every United States Marine to this day.

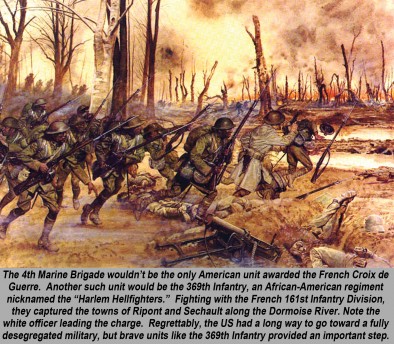

The French were also impressed. Belleau Wood was renamed “Woods of the Marine Brigade.” The entire 4th Brigade was awarded the Croix de Guerre. To this day (100 years ago this month), members of the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments still wear the French “fourragère” decoration on the left shoulder.

They’d paid for such honours. By the time the battle was over, the Army and Marines of 2nd Division had lost 1,811 killed among almost 9,800 total casualties, a shocking two-thirds of their beginning strength.

As for the Germans, their advance on Paris was well and truly stopped. Ludendorff had already racked up a staggering butcher’s bill with his 1918 offensives, first with St. Michael, then Georgette, then Blücher. One more attack, code-named the Gneisenau Offensive, had already been put down by French and American forces.

Now it would be time for the Allies to strike back. The action would shift away from Paris and back north in Flanders, where British, Belgian, Australian and French troops would launch the Fifth Battle of Ypres, and finally shove the German line back toward an ultimate conclusion of the Great War.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this look at the Blücher Offensive and the Battle of Belleau Wood. What famous units do you admire from the Great War? Have you ever considered trying to recreate their battles on the table top?

Post your comments or questions below, and keep the conversation going on Centennial Gaming in the Great War!

"For United States Marines, to this very day, Belleau Wood is legend..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"“Come on, you sons of bitches! You want to live forever?”"

Supported by (Turn Off)

![10mm Medieval Miniatures! Azincourt English Army Review | Wargames Atlantic [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-azincourt-english-army-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

![Play WW2 Commando Operations With Butcher & Bolt [Updated]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/03/relaunch-600-338.jpg)

How about Monash and the aussies?

Thanks for kicking us off, @richardd – The battles around Villers-Bretonneux, which involved General John Monash and his Australians, are looked at in some detail with the Georgette Offensive, St. Michael, and the battles around Villers-Bretonneaux in Part 03. @jamesevans140 (Australian) also gets involved in the comments talking about some of the “quiet rebellions” and experiences of the Australian Army.

I don’t think @neves1789 had any Australian figures / miniatures to feature them heavily in the Part 03 writing. I know I didn’t. Even to cover the US Marines here, I had to build my own game (or at least, a new edition to Barry Doyle’s print-n’-play Valor & Victory).

So yes, “Monash and his Aussies” sounds like an interesting topic, and perfectly timed for a 100-year anniversary.

When do you publish? 😀 😀 😀

@richardd Good catch! There’s just so much that we weren’t able to put in 🙂

Thanks @richardd and @neves1789 – Monash and the Australian Corps (Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, BEF) comes in more at the Battle of Hamel, 4 July 1918, and subsequent battles leading into the Hundred Days at the Battle of Amiens (8 August). So they’re a little outside the scope of this series. We return to them in a vengeance in later articles:

https://www.beastsofwar.com/board-games/armistice-centennial-part-one-the-hundred-days/

“The Marines were not as experienced, sometimes even attacking in the wrong direction after losing their bearings in the smoldering, misty woods. But they smashed any position they hit, often with bayonets, rocks, or bare hands”…

Yes, this sounds like some other Marines I have known in the past. 😉

“Marines you have known in the past?”

Are you breaking up with me? 😀 😀 😀

Haha, time to pack your bags 😀

Make room on your couch, please! 😀

The movie is probably The Lost Battalion, I remember seeing that one years ago. Pretty solid war movie to be honest unlike some other WW1 movies.

The many German armies from their former kingdoms is indeed an interesting aspect from the war, to a certain degree similar with the British. Even during WW2 they still had their Wehrkreiss system that recruited locally 🙂

To game Belleau Wood, I’d advise to mix up the terrain a bit. For the first US attack, you could have half of the table open ground and half wooded to give that transition and make it harder for the attacker once they get into broken ground. For further battles in the woods you could use night fighting rules to simulate the density of the trees. Just some quick ideas 🙂

Sven 4 the win. Great ideas. Accepted!

That’s why two heads are always better than one. 😀

Great article – you usually think or Marines in places like Asia, the Middle East, the Pacific, so on. Interesting to read about them heavily engaged in battles in Europe. Do the results of these games reflect some of the results from historical events?

very often they do, @pslemon – in fact that’s one of the dangers, is that your games start to recreate history TOO faithfully and they wind up more as reenactments than actual games.

The usual model I use for playtesting is to research, design, and build the game and scenario as best I can, then play it a few times making all the same decisions as the historical commanders. If the games shake out with very different results to history, clearly your model isn’t working, and make fixes. If the games come very near to the historical result with historical decisions, then you have a reasonable model for your “thought experiment” and you can go back and play the game some more, except now “ask the game” what would happen if commanders had made different decisions in tactics, method, or doctrine.

Needless to say, using proven systems, keeping good records, and building on past results is a good way to cut down on the front-end workload in this process. 😀 But this kind of flexibility and “we can play this game three times today – with the armies we BUILT in three hours yesterday” are big advantages hex & counter games have over miniature wargames.

It’s a different definition of “hobby,” where you “build and paint” with research and data instead of plastic and paints. 😀

More great stuff! I love all the “moments” you include in these articles. They add a real life feeling the the facts. I especially love the quotes like “retreat, hell we just got here!”

Trust me, there is no shortage of anecdotal stories about this battle, at least from the viewpoint of the Marines. It’s almost dangerous how much “legend” is poured into this fight, it can actually skew peoples’ perceptions.

I forgot to ask, Why is it so many of the “Famous” units are famous through multiple wars? It’s obviously not the same commanders or soldiers, so why would say the 2nd and the 5th be bad-ass in WWI and Vietnam?

I think pride may have a lot to do with that if you are in a unit you grandfather fought in that’s a lot of history to fail if a Battle you fight in was lost think of the family/army prestige. @gladerunner

Thanks @zorg I bet that would come into play. @oriskany can Marines request a unit to serve in?

I think they may ask your preferences that may go for not at a times of war but.

Many replies here – let me get started.

OK, @gladesrunner – a lot of these Marine battalions and regiments appear time and again because we have to remember how small the Marine Corps actually is, and how often it’s the first force sent in to American conflicts around the world.

Just as an example – 2/5 Marines has its own website and wikipedia page that details how often this unit has been in harm’s way.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_Battalion,_5th_Marines

Regarding requesting transfers, I have no idea what the policies were in 1918. In more recent times, Corps personnel officers do allow for this, but orders come first as well as openings within the battalion itself. Again, we have to remember how small these units are, a battalion only typically runs (depending on its type and mission profile) about 400-800 men.

The vast majority of the time, a Marine receives orders to a certain unit and reports.

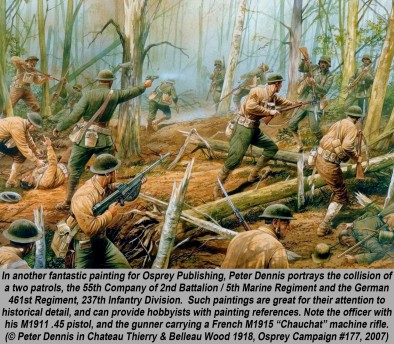

Another good informative read did the Marine officer’s receive extra casualties with the uniform difference’s like with the second WW helmet ranked markings.

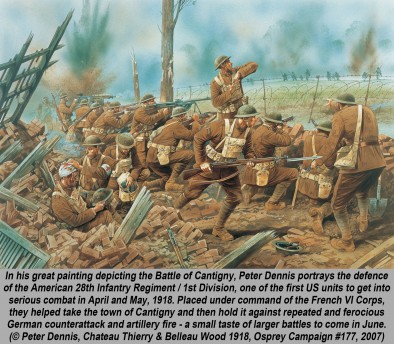

Marine officers did indeed sometimes wear different uniforms than enlisted men in World War One. Referring to the Peter Dennis painting, we see the officer is wearing an olive green on green (and carrying a pistol) whereas the enlisted men are wearing mostly two shades of khaki. This is historically accurate. The actual Marine uniform in this period to my knowledge is the officer-style olive on olive, but often Marine units at this time had to rely on US Army issue gear for the rank and file. Note in the Peter Dennis painting their uniforms for the enlisted men are not … well, uniform. 😀

Marine officers, at least platoon officers, often take higher casualties because the would often lead from the front. This is anecdotal, though, I don’t have actual numbers to support it. Marine NCOs were the ones who took the real casualties in most of these 1850-1950 battles.

As far as the helmet markings on US helmets in WW2, I’m not sure they contributed to higher casualties. I’m assuming you’re talking about the horizontal white bars often seen on the back of NCOs’ helmets and the vertical bars on officers. This is so the men knew who to follow in the chaos of combat. The Germans would not see them from the front.

Any higher casualty percentiles that people might have evidence for may be coincidental, resulting more from the junior officers and NCOs leading from the front, rather than the markings on the helmets. I’d be surprised, but interested, to see evidence to the contrary.

Probably Hollywood elaboration’s exaggerating casualties.?

I certainly don’t contest that platoon level officers and NCOs sustain higher casualty probability curves (especially NCOs) – I’m just not sure I would attribute it to what American squad / platoon leaders had on the backs of their helmets.

I think a lot of casualties of the American forces at the end od WW1 was down to a feeling that they had to prove themselves. There are a few instances of the Americans charging blindly at the Germans in the latter stages of 1918 where a bit of caution would have saved some more men

At the end of World War I, I would totally agree. Some quotes I have found in the course of research for these articles:

“Americans are good fighters with nerve and recklessness.”

– – – Arunlf Oster, Lieut. of Reserve

“There were only a handful of Americans there but they fought like wildmen.”

– – – Antone Fuhrmann of Mayschoss

“I had been told by other soldiers that the American infantryman was reckless to the point of foolishness.”

– – – Peter Bertram, German Reservist

“The accuracy of American artillery fire…could have been considerably improved upon.”

– – – Karl Diehl, German Soldier

Snippers may account for some of the extra casualties it’s part of there job eliminating command personal.

“Snippers?” Oh no, is @dignity loose in the studio again, castrating all the male miniatures? Snip! Snip! Clip!

Just kidding, I know what you meant. 😀

Lol.

I like everyone’s new monster icons. 😀

The Over the Top rules by the now sadly departed Greg Novak has a nice Belleau wood scenario in it. If I can get my scanner to work I’ll post it up here

Holy hell, @torros, you didn’t tell me Over the Top was a GDW game! Definitely a lot more interested now.

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/16673/over-top-command-decision-series-game

Its a redskin of command decision but plays well. Still have a copy somewhere

Yeah, and to be honest, I never knew “Test of Battle” and Command Decision were associated. For GDW I was always into the “Assault” series, followed by the more accessible “First Battle” series (and of course RPGs like Twilight 2000 and Traveller 2300).

I don’t really agree with what BGG says about these being “operational warfare” scale games – I don’t think they know what “operational” wargaming is 😀 but that might be a BGG thing and not a GDW thing.

Anything with Greg Novak or Frank Chadwick’s name on it is worth a look. These days anyone who produces a couple of games is now called a veteran designer. Frank Chadwick truly is one

I would agree with that 100% re: Frank Chadwick, if only for the GDW Assault series.

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/8284/assault-tactical-combat-europe-1985

(The game Team Yankee wishes it was)

I meant reskin of course

😀

Good addition to a whole bit of WW1 that I was ignorant of , Thanks Jim for filling in a gap with a nic potted history of campaign.

No worries at all, sir. Expanding the community’s knowledge of the “lore” and “fluff” – hopefully to heighten interest and inspiration into historical wargaming, is what the Historical Editor is all about. 😀

Good to see the Americans up and running, which was almost a miracle in its self.

This is what amazes me. Go back just a couple of years. The American army, what army, they had no army. Her combined military might ranked her 19th most powerful just after Hungary. So they had to build a real army but before you can do that you have to build training camps, many of them as large as small towns out in the wilderness. This means getting the building materials and skilled workers out there, meaning new roads and railways. Now you have to cloth, equip and feed them them from industries trying to gear up from domestic use. Then you have to build or buy transport ships to get them to Europe without missing the war. We are used to American might to produce things since WW2 but in WW1 they just don’t have it and must literally start from scratch.

To get there in time so not too miss the war they had to send most of their men from boot camp straight to Europe with no chance to fully train them up for combat. After the initial rush the US soldier arrived with better trained. But it was a break neck rush at first. So I have been always amazed that the US did not miss the war at all.

The color of their uniforms was olive drab – pink. The US marines still used this uniform color going into WW2 and changed over when they traded in the British tin hats. From what I have seen it is similar to the WW2 color but on a warm pallet rather than a cold pallet color. Well that’s the official regulation. Given the insane rush the color variance would be far greater than it was in WW2. Back then uniform colors were all preceded by Olive Drab, so you have OD red, OD mustard, etc. OD seems to mean military color.

It is all too easy from our modern perception of the US not to think to ask whether they were ready. They were thrown into the war had first, no wonder they did not have a head for all things military. It was great for Paris that they had the stomach for battle. 🙂

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – Indeed, before the end of World War II, America had always had an inherent mistrust of a standing army, they saw it as too much of a danger that it could be subverted and misused by a popular general or corrupt President or some such. So they’d never have a standing army, only a cadre, that would then be rapidly multiplied by a citizen levy in times of need.

Before entering World War II, America’s army was something like 27th in the world, right after Rumania or some such. I am not surprised to read that their standing before entering World War I was similar.

Of course, with the Cold War starting before World War II even ended, this attitude finally changed, but even through Korea and Vietnam a draft levee remained in place. It wasn’t until after Vietnam that America’s military became fully “professionalized” But we’re getting off topic.

You know, I never really noticed the hue in those shirts, but looking at that second Peter Dennis painting again, there really is almost something of a reddish tint to that “khaki.” The term “OD Pink” is certainly new to me, though. 😀 Can’t really deny it, however.

With the “Paris was fortunate” angle, I would only remind readers once again – and this is NOT meant as any kind of “correction” at you or anything – that these two American divisions made up only a small part of the French Sixth Army and other formations that finally stopped the Blücher-Yorck Offensive.

I only keep adding this because I know that sometimes I can come across as a “Team America” champion (even though my last two article series have dealt almost exclusively with traumatic American defeats). The Americans aren’t really mentioned anywhere in this Great War series except here (spoiler alert – they’re really not in Part 05 very heavily) – so while I wanted to make sure I covered their contribution here, in the overall scheme of the Allied line in March-June 1918, they’re not a terribly widespread presence.

British and French troops fought and won the bulk of these battles, along with Belgians, Australians, and Canadians.

Now when it came to the St. Mihel and the Hundred Days, that balance would change somewhat. Yet as they say in Conan …

“… but that is another story … 😀

Speaking of part 3 @oriskany, I left a final comment for you there if you care to read it.

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – I will definitely check it out and thanks for the heads up. Four threads in progress at the moment … 😐

Thanks for you reply @oriskany.

I accept what you are saying about the US only being a small contribution as this was the case. However 2 divisions are 2 very big divisions. By this stage of the war a US division was nearly 3 times the size of an Australian division.

I personally would not bother about the team America thing. I can’t open my mouth without being team Australia. As long as it is done in an honest way each team brings just that much more flavour to the table expanding what the other sees, surely this is a good thing.

The best part of our long term relationship is that if one does over step the mark the other can tell the other to pull their head in, without malice.

The names for colors in respect to uniforms is different to those of WW2. I came across this a few years ago when I was researching the official uniform colours for US, German, British and Canadian uniforms. The WW1 American soldiers referred to the uniform as pinks, but I don’t know if that was the practice for the marines who wore them a lot longer.

To be perfectly honest I believe you could simply paint up WW1 US infantry using WW2 colours. At 15mm scale the difference would be hard to pick out. If you gave your miniatures a shadow wash of warm brown rather than green or grey you would not be far off the mark anyway.

The US in the past has always, excluding the 80s, downsized their military after the crisis. So when presented with a new crisis they have had to ramp up to meet it. But never has this ramp been so steep as for WW1 and the AWI. So I remain amazed at the speed at which the US got a mostly trained field army into Europe. Like everyone else involved they should have been talking about 1919 or 1920.

When you speak of a mistrust of a large standing army I think it goes all the way back to British rule. A large standing army puts you under the thumb. You don’t need democracy or even representation when someone has a large standing army to tell you what you need. To some degree this echoes down the ages leaving a strong passion to ensure that you will never see again a large standing army telling you what you need.

It resonates in the Australian character as well. We refer to the British army in Australia as the rum corps. A degrading term to reflect that these soldiers were second rate compared to those serving in Europe but taken from the fact they were paid in rum, doing not much for their discipline. The term rum back then referred to any number of spirits spillage that ended up in a container, drunk at you own risk.

Just finishing off the remarks from part 3. We have found out here that taking people from the same area has some very strong advantages but at a terrible cost.

Good point about the size of American infantry divisions. I was also a little surprised to learn about the size of German infantry divisions even this late in WW1. Each of them seem to be built around two full brigades according to my sources on Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood – and not brigades like many other armies uses the term “brigades,” i.e., glorified regiments. But actual stacked regiments, themselves made of stacked battalions. How large these smaller constituent units were isn’t 100% clear or consistent (obviously thus effecting the size of the overall whole), but they seem pretty large compared to World War II counterparts.

Totally agree about WW2 vs. WW2 colors. At 15mm – 1940 BEF could also work (in a pinch) for 1918 British rifles, assuming you had 1918-specific artillery, support weapons, and vehicles.

I also agree that I “personally would not bother about the team America thing …” The concern for me is that it’s not always personal, I’m writing for 70,000 BoW subscribers here. 😀

Absolutely agree about the roots of America’s traditional fear of a standing army extending back to the American Revolution. “Citizen militias” winning “battles” like Concord and Bunker Hill, Washington’s popularity posing a threat to a bankrupt and ineffectual Continental Congress, his officers mutinying against him and demanding they march on Philadelphia and take over Congress, the movement to anoint Washington as the first “King” of America in 1781-83, all of this is why he could get the standing army he wanted of 40,000 men for the duration of the war. The thought terrified the Congress, the state assemblies, and the people at large at the time, it took American almost 200 years to shake off that terror (perhaps replaced by a new terror of Soviet mushroom clouds).

Great article and series of articles Oriskany… I’ve used Bolt Action for 1914 themed games but im sure it would work as well, if not better, for 1918. I suppose in some way gaming Belleau Wood could be a little like gaming Pickett’s Charge, you know the result but can YOU do better than they did on the day… ?

you know the result but can YOU do better than they did on the day… ?

@firelock22 – this is exactly how we try to design scenarios, at least in larger, unit-based, non-skirmish level games.

1) Find a battle you want to recreate, based both on general interest but also on available detailed information.

2) Build the most faithful, detailed scenario you can, within the construct of the system in question.

3) Run the game 3-4 times, always making the same decisions as the historical commanders and seeing if the game delivers approximately the same result as historical events. make adjustments as you you, and write down and record everything.

4) Once you have a working “simulation model,” take the “training wheels” off and start running the scenario freely, making new decisions based one new tactics or strategies.

5) The historical objective of the attacking side, and the degree to which they historically succeeded or didn’t succeed, is the “draw line.” That result is a “draw.” Do more poorly than that, the Defender wins. Do better than that, the attacker wins.

In your Pickett’s Charge example, the divisions of Pickett, Trimble, and Pettigrew are probably all doomed no matter what. But if they reach the stone wall and hold out for three turns instead of one, or put a largercrack in Hancock’s II Corps, or take only 40% casualties before falling back instead of 50-60% … they win, even though of course they will still never really break that wall and take that ridge.

Conversely, the Federals will always “win” that battle. But if they can break those three divisions while they’re still crossing the Emittsburg Road, or launch a counterattack afterwards that splits Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia … i.e., if they do “better” than historically …

I’ve found that this mechanic often puts a lot of pressure on the “winning” side. Germans in 1941 Russia, Israelis in 1967 Sinai … yes, you’re “winning” to an embarrassing degree … BUT the expectations are so high that the “winning” player often has a terrible time trying to meet those steep victory conditions, within very strict casualty limitations or very tight timelines or other constraints that balance the asymmetrical nature of the battle.

Started a project here showing my WW1 6mm stuff, its 1914 themed so plenty of open warfare and cavalry! (i had to convert the lancers though)