SITREP Podcast OPS Center Episode 8: Ground Ops & Wrap Up

June 5, 2019 by stvitusdancern

Jim takes us on one final journey to the Falkland Islands to talk about the ground war and wrap up this series of the OPS Center. We hope you have enjoyed this series on the Falklands War. Be on the look out for future episodes as Jim guides you through another modern conflict.

Where should Jim take us next?

![Perfect Call Of Duty-Style Miniatures? Wargames Atlantic’s Operators Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/unboxing-wargames-atlantic-operators-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

Another good one Jim

Thanks very much. 🙂

Excellent stuff Sir, certainly brought back memories. Look forward to the next.

Appreciate it, @gremlin – We’ll be on break for a short while, but later on in July please keep up with us on our Podbean and Youtube channels. 😀 😀 😀

Sitrep YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCrsewixu9dXUIMTQKJYPuEQ

Sitrep Podbean:

https://sitreppodcast.podbean.com/

nice one @oriskany the Atlantic conveyer choppers losses fair messed up the plans. have you considered trying attacks with the missing air support?

Thanks, @zorg – the helos lost aboard SS Atlantic Conveyor were mostly transport birds. Close air support in the Falklands was mostly a Harrier thing, as opposed to a helicopter gunship thing. So if you’re talking about removing the helos from the British transport capacity (at least for Thompson’s 3rd Commando Brigade), well the historical record already has that “baked in.” 😀

The “alternate history” might be to put those helos BACK IN to the mix. This wouldn’t make much difference in terms of firepower, but would allow first-wave assaults on high ground positions like Two Sisters, Mount Longdon, and Mount Harriet much earlier, and perhaps from different directions (air mobile assaults).

Nice wrap up to the series! I love planes and boats, but its boots that win wars!

😀

Funnily enough, in the parallel Thread I found myself talking about the old-fashioned non-waterproof boots of the Elite British forces vs. modern waterproof boots the Argentinien conscripts wore.

… But seriously, if there is one thing that @oriskany has taught us through his many articles over the years: regardless of if a war is fought on Land, Sea, Air, Cyberspace or Outerspace or in any combination thereof… at the end of the day, what wins wars is good logistics. ?

Serving in a military supply MOS (in a bygone prehistoric era, of course) probably contributes a shameless and unhealthy bias to my views on the matter. 😀

Nice one @oriskany – Enjoy the summer brake

Thanks, @rasmus – will do.

What a tremendous series. I learned a lot and the production quality is top notch. Thank you

Thanks so much for all the support, @stvitusdancern – and of course for the opportunity to present for Sitrep. 😀

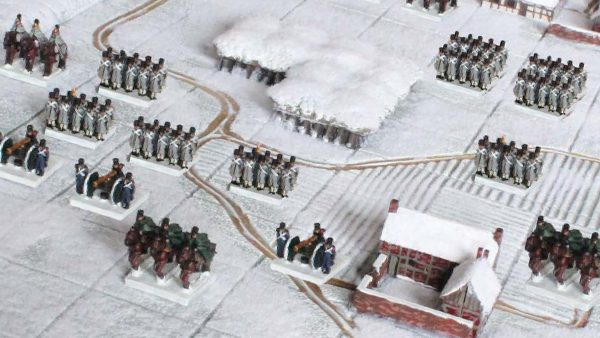

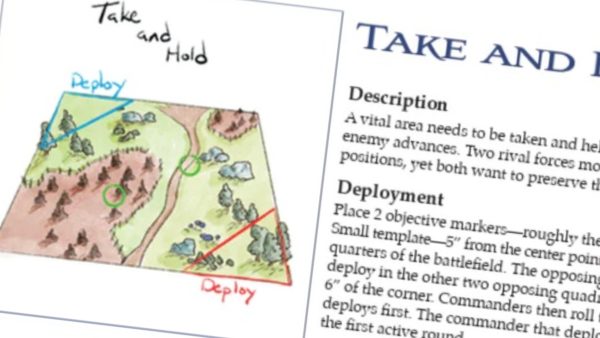

Yes, absolutely. The Visual Presentation is excellent – with the photos, maps, graphics and text captions showing and illustrating perfectly what Jim is explaining on the audio.

Thanks very much @aztecjaguar ! 😀 Comments like that are what make it worth all the work.

Thanks Jim, brings it all back. Is there any truth in the rumour that “ident. friend or foe” recognised incoming missiles as British. Thanks again.

@goban – Are we talking when the Exocets were heading for HMS Sheffield?

If so, man … there are a ton a factors in that one. Notice in the video I didn’t even try to get into that.

This report was suppressed for decades, not only to cover up embarrassment for the Royal Navy, but also because the UK was trying to sell off other Type 42 destroyers at the time.

Now released, the report lists:

Marked “Secret – UK Eyes Bravo”, the full, uncensored report shows:

Some members of the crew were “bored and a little frustrated by inactivity” and the ship was “not fully prepared” for an attack.

The anti-air warfare officer had left the ship’s operations room and was having a coffee in the wardroom when the Argentinian navy launched the attack, while his assistant had left go to the bathroom.

The radar on board the ship that could have detected incoming Super Étendard fighter aircraft had been blanked out by a transmission being made to another vessel.

When a nearby ship, HMS Glasgow, did spot the approaching aircraft, the principal warfare officer in the Sheffield’s ops room failed to react, “partly through inexperience, but more importantly from inadequacy”.

The anti-air warfare officer was recalled to the ops room, but did not believe the Sheffield was within range of Argentina’s Super Étendard aircraft that carried the missiles.

When the incoming missiles came into view, officers on the bridge were “mesmerised” by the sight and did not broadcast a warning to the ship’s company.

>>>>>>>>>>>

At least for me, the proof is simply that … another Type 42 destroyer, HMS Glasgow, DID spot the aircraft and the missile. So this wasn’t a systems issue or a technology issue, but a human issue.

That said, in another incident, when the Argentinians fired more Exocets at British warships, they deployed chaff to confuse the missile. The countermeasure worked. Sadly, the missiles reacquired another target, the container ship SS Atlantic Conveyor, hit her and sank her.

The de-classified report on the HMS Sheffield is all new information to me – I had no idea it was a series of totally banal and avoidable human errors – all just happening at once and at the worst possible time.

To think that the ship named after my home town was hit and ultimately sunk due to a few key crew members being either bored, on a coffee break, on the toilet or just staring in disbelief at the approaching aircraft and/or missile… it is just so tragic – especially given the loss of life on the ship.

Indeed, @aztecjaguar – the ship herself was fine. Okay, the aluminum and plastic used in the construction of her superstructure wasn’t the best, but very normal for the time. The path that leads to this seemingly bizarre choice is sadly logical:

Anti-ship missiles basically never miss, and pack enough firepower to blow almost any ship half out of the water.

Ergo, the idea of “armor” on warships in the mid 1970s seemed pretty pointless.

So ships were built without armor. This made them faster, cheaper, more fuel efficient, and allowed more weight and space to be reserved for what really counted: electronics.

Fair enough, but these electronics have to be mounted high in the ship, in ever-expanding superstructures. Well, as the superstructures grew larger and the hulls grew lighter, the ships became TOP HEAVY and less sea worthy.

So how to save weight on superstructures? Lighter materials: like aluminium and plastic.

Fair enough, since “metal armor” isn’t going to save you anyway from an Exocet (*or Tomahawk or Harpoon or Kingfisher or other contemporary ASMs). But aluminum and plastic … burns. And there’s the real fate of HMS Sheffield.

As we covered in Part 03, the missile that hit her actually never even exploded, as incredible as that sounds. But the raw kinetic impact and the horrific splash of unspent fuel pretty much lit the whole core of the ship on fire from the inside out (I think the missile actually wound up in the galley – and the water mains and pumps were also among the infrastructure hit in the initial impact). So once the fire started, it just became impossible to ever really bring it under control. Even other ships that came along side to lend assistance with water hoses, firefighting teams, and electrical power, wound up making no difference. Sheffield would sink 10 days layer.

But the Type 42 was not a bad air-defense destroyer in concept, especially when ships like HMS Glasgow and later HMS Exeter and HMS Cardiff were paired with a British Type 22 Frigate. This matchup was so successful they called it the “Type 64 Combo” – the root of its success coming from the Type 42’s longer-ranged Sea Dart air defense missile system “layering” atop the Type 22’s Sea Wolf short range air defense missile system. Anything that got through these two layers could then be cross-engaged in a scissor between the guns of both ships.