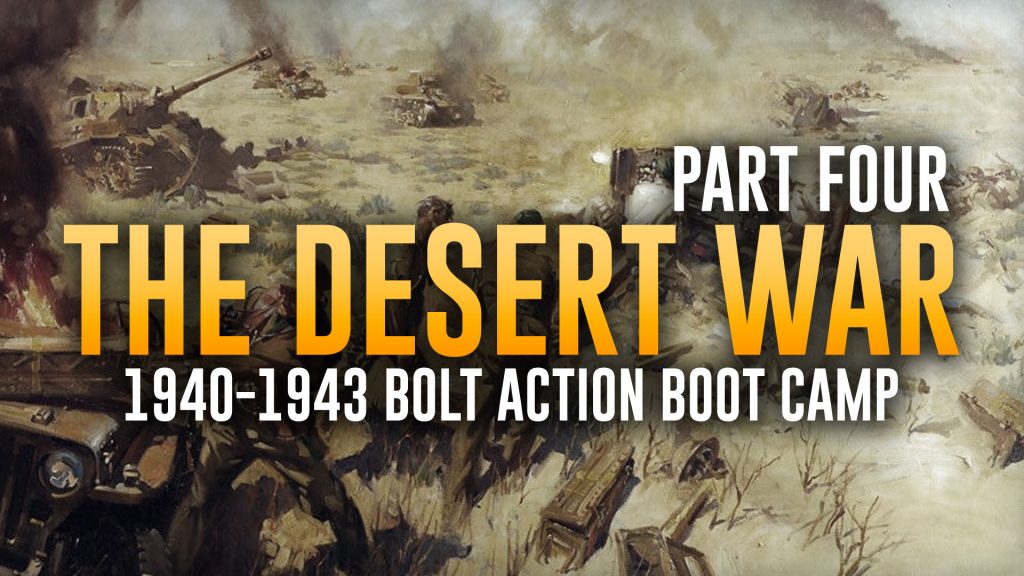

The Desert War: Bolt Action Boot Camp Preparation // Part Four: Turning The Tide

September 10, 2018 by oriskany

For the past three weeks, we’ve been gearing up for the imminent Bolt Action Boot Camp with this article series looking at some of the more decisive desert engagements of World War II, fought primarily in North Africa.

In a nutshell, our aim is to help players and hobbyists approach this subject with a little more confidence and perspective, offering as much background and context as they may be interested in before the event kicks off at the end of September.

Read The Original Article Series Here

For those just joining us, our progress thus far has been presented in Parts One, Two, and Three. We’ve seen the Italians start this war almost by accident, followed by the British coming within inches of victory only to have Rommel show up and hurl them back. Through the “Crusader” battles of late 1941 and the Gazala offensive of 1942, both sides have thrown heavy blows as the Desert War see-sawed bitterly back and forth.

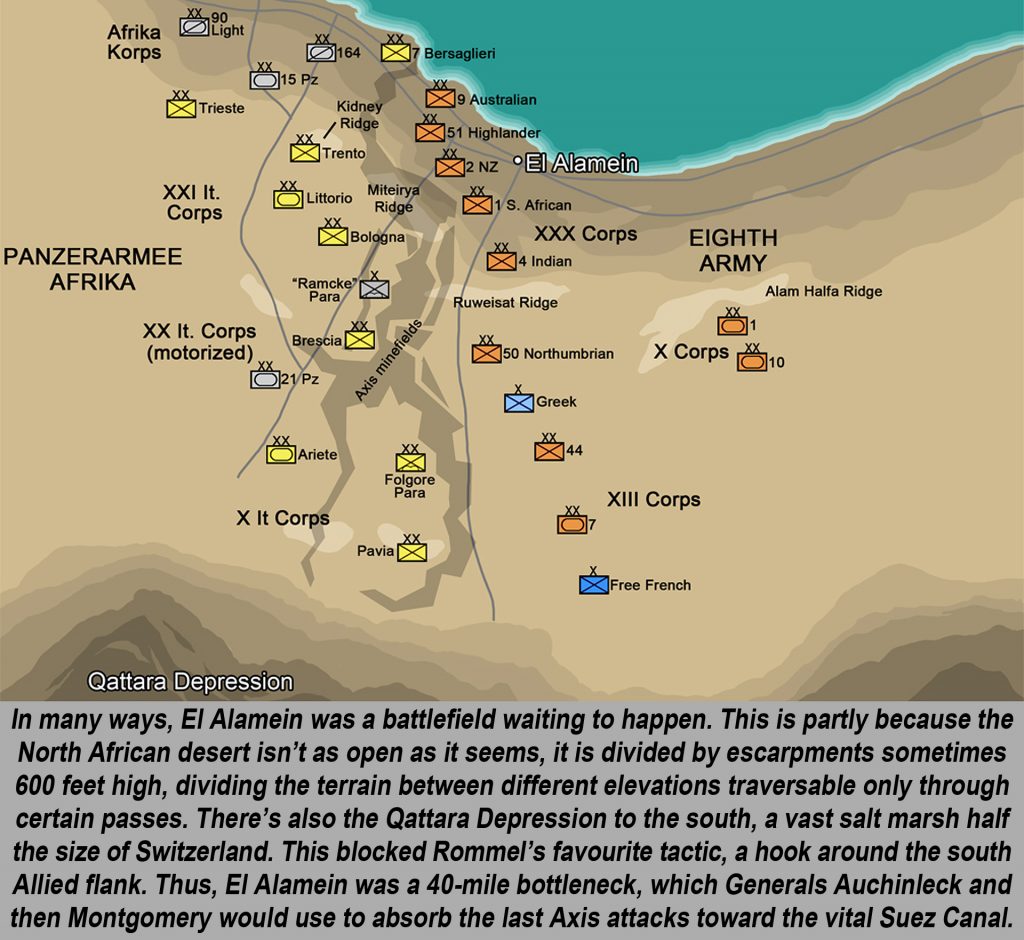

But in the late summer of 1942, after two years of attack and counterattack, a crisis point has finally been reached. Having been thrown back halfway across Egypt, the Allies can retreat no further. Having exhausted their supplies and reinforcements, the Axis can wait no longer. The Allies are out of space, the Axis is out of time. One way or another, a decision will now be made at a tiny desert railroad town...called El Alamein.

As we saw last week, “Panzergruppe Afrika” roundly defeated the British and their Commonwealth allies at the Battle of Gazala. Rommel was thus able to overrun Tobruk (which had held out for 240 plus days the last time the Germans had been here) and push the Allies back into Egypt. The British attempted to make a stand at Mersa Matruh but were outflanked and defeated again. This time the retreat took them all the way back to El Alamein.

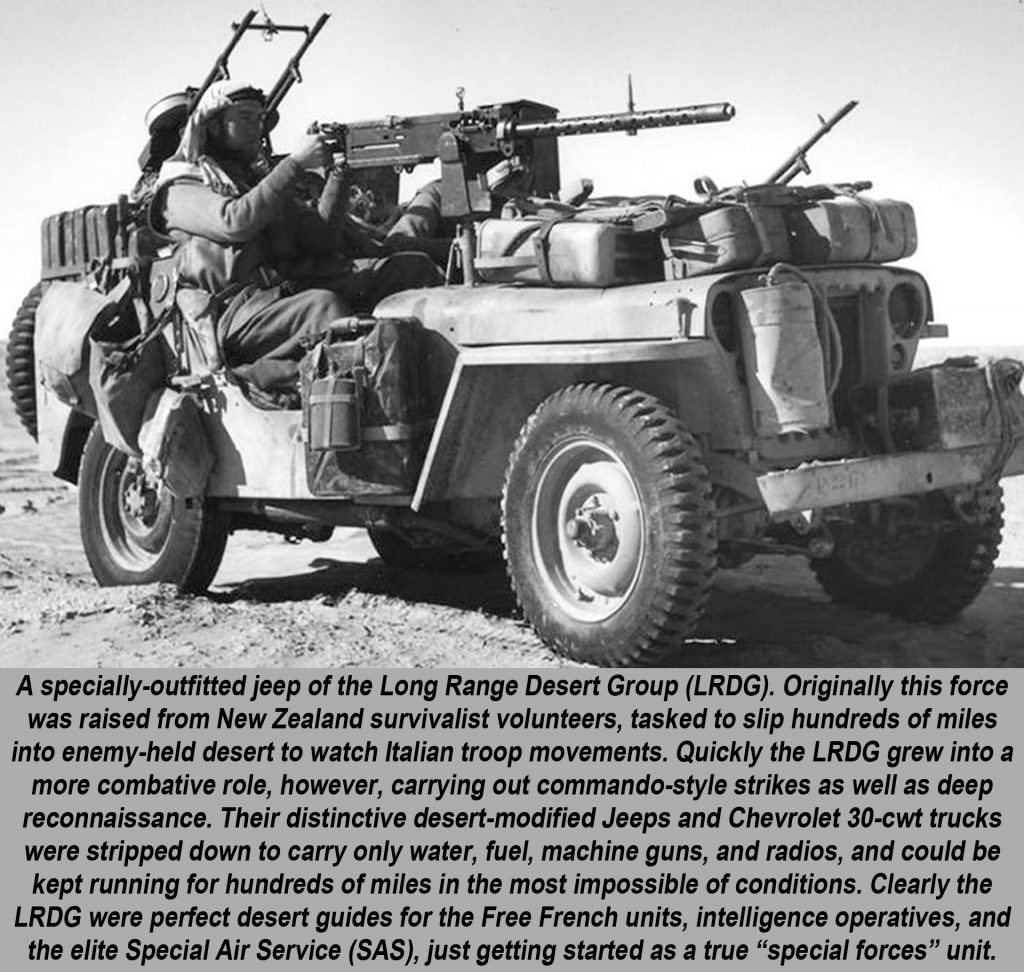

In direct violation of orders, Rommel went after them. His superiors knew this was a bad idea, to push this deep into Egypt against numerically superior forces would badly overstretch his already-vulnerable supply lines. The British knew it, too, and were using every weapon they had to strike at these supply routes. One of these weapons was the Long Ranged Desert Group (LRDG), which was about to carry out their most famous raid.

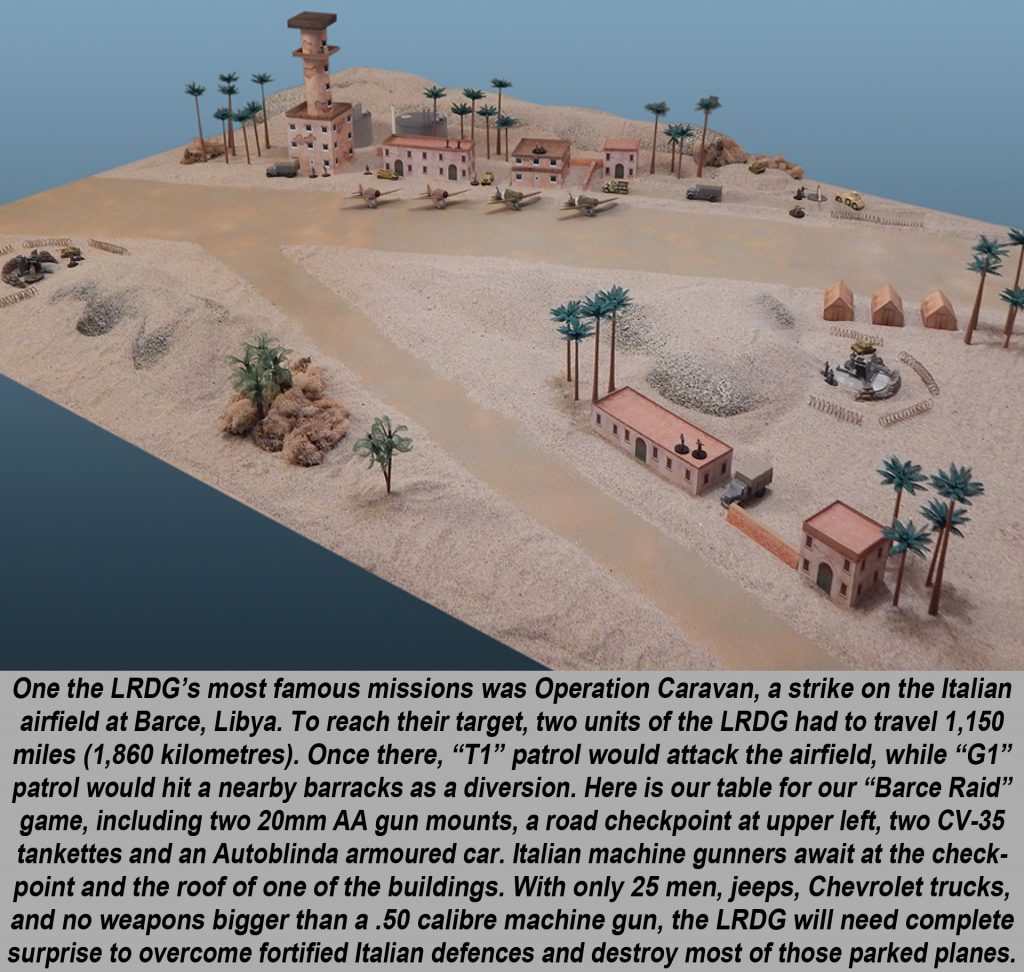

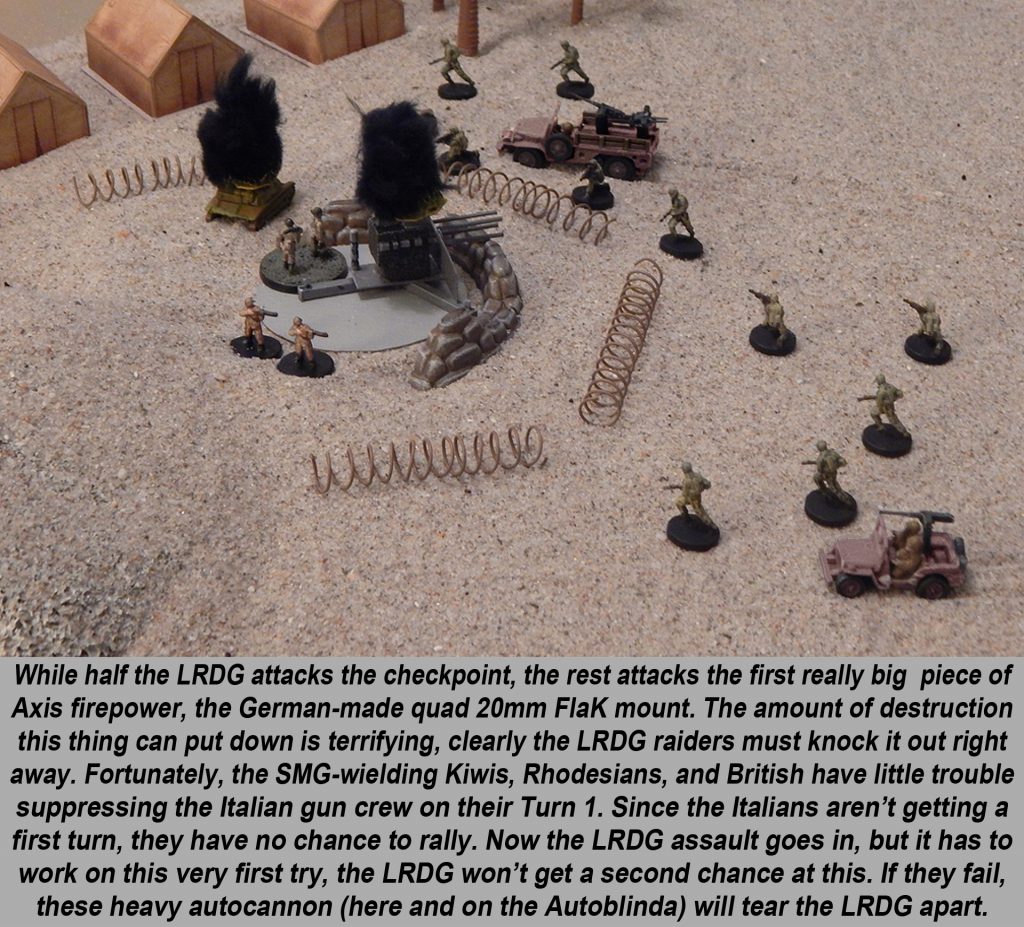

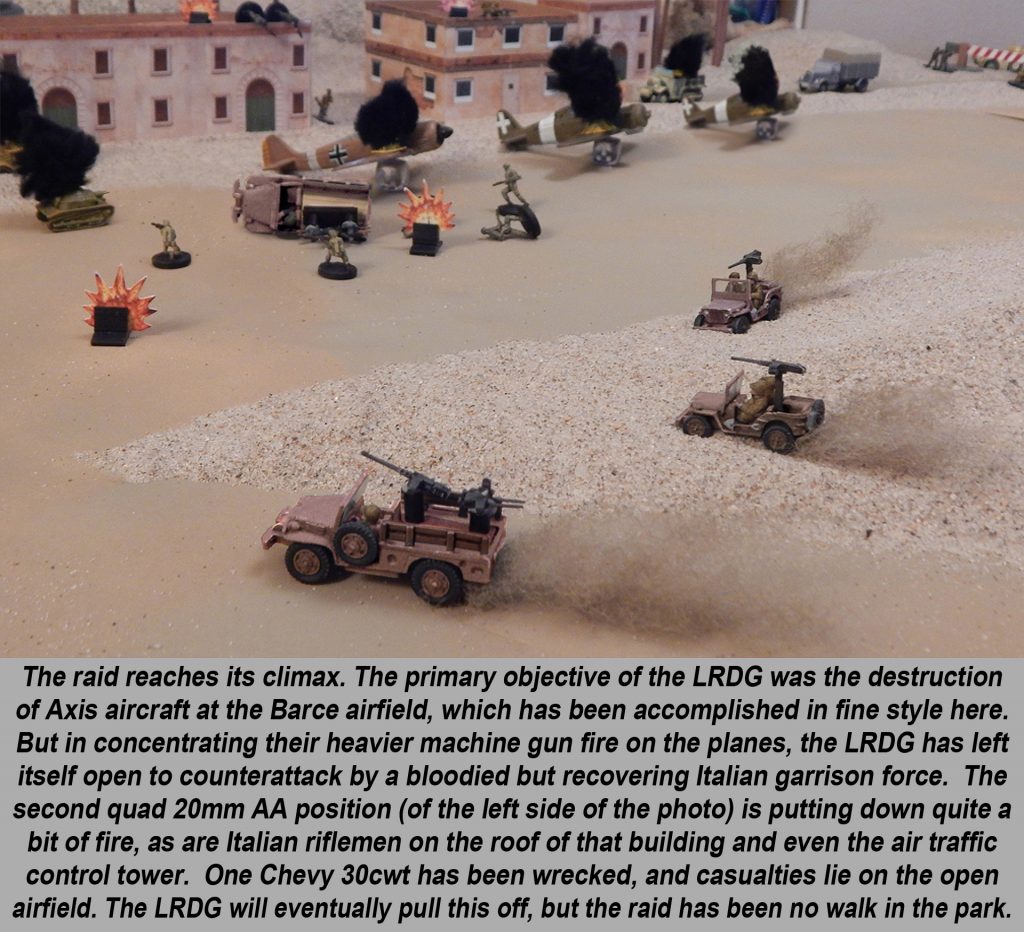

“Operation Caravan” was an LRDG strike at the Axis airfield at Barce, on the northern coast of Libya. It was part of a larger series of commando-type operations aimed at disrupting Panzerarmee Afrika’s lines of communication and supply, involving the SAS, British Commandos, the Royal Marines, the Royal Navy, and even a battalion of line infantry.

Interestingly, the Italians largely defeated all of these operations except Operation Caravan. The operation is also unusual because the LRDG was usually deployed as a reconnaissance force rather than a “commando strike” unit. Experts in desert navigation and survival, they often took the SAS to their targets, rather than strike the targets themselves. But as they certainly showed at Barce, the LDRG could “get messy” with the best of them.

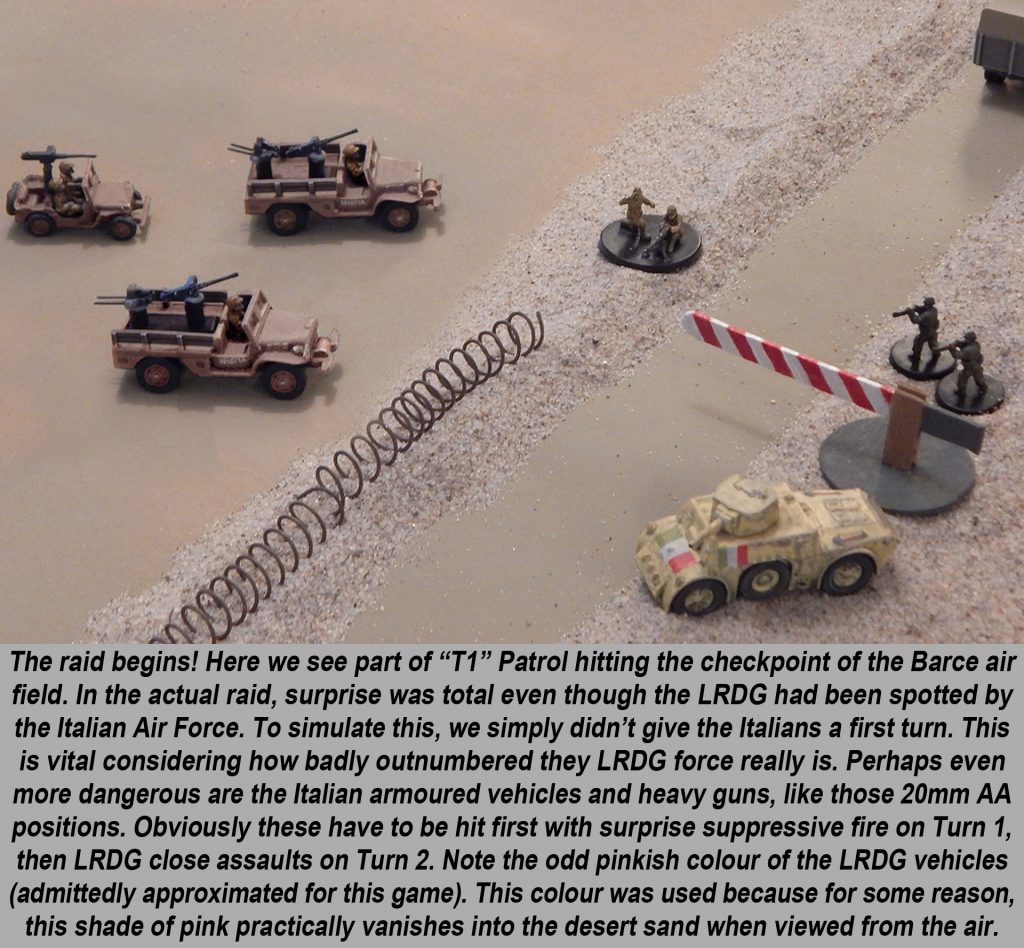

Ironically, the LRDG’s attack on the Barce was not a complete surprise, they’d actually been spotted some time ago by the Italian Air Force. Throughout the career of the LRDG, Italian air reconnaissance was almost always the biggest threat, besides of course the lethal conditions of the desert itself.

However, the Italians at the airfield did not expect the LRDG attack to come straight off the main road, especially since one of their own columns had just passed up that same road. These Italians and the LRDG actually passed each other in the night, going so far as to wave hello. Such was the “fog of war” in the desert, especially in darkness.

The raid was a success, with just four of the LRDG attackers wounded. Accounts vary on how much damage they did, ranging between 16 and 32 aircraft destroyed. But four LRDG vehicles had been wrecked, so many of the men had to walk across the desert back to other LRDG rendezvous points. They were attacked from the air and harried by Italian counterattacks, and some LRDG raiders were captured.

This just goes to show that, despite the movies, “special forces” are just as fragile as any other troops. As units, they’re even more fragile because of their small size and lack of heavy weapons support. These operations are complex and dangerous, and it doesn’t take much for something to go awry...especially with your ride home.

Lots of people are bringing LRDG-themed armies to the Boot Camp. Warlord has some great lists to work with if you’re interested in giving the LRDG a try. I’ve actually started building one myself – the very first 28mm miniatures I’ve ever worked with. This is just one of those units that screams Hollywood, reading their exploits sounds like the script to countless 60s and 70s action movies...except that for these men, the adventure was all too real.

Showdown At El Alamein

Back at the Alamein Line, meanwhile, the Eighth Army was trying to pull itself together after the twin disasters of Gazala and Mersa Matruh. Now set up at the superb defensive position at El Alamein, they knew there could be no further retreats. Alexandria was just ninety miles behind them, with Cairo, the Nile, and the Suez Canal beyond. After El Alamein, there was also no further defensive position. At El Alamein, it was stand or die.

Fortunately, things finally started to turn around for the Allies. In early July, Rommel hit them yet again in a series of attacks. But with the Qattara Depression blocking his favourite “hook around the south” strategy, came to bloody grief. Rommel had come to the end of his leash. Generals Auchinleck and Ritchie hit back, heavily mauling Panzerarmee Afrika but failing to push them back. This “First Battle of El Alamein” is largely considered a draw.

Meanwhile, Winston Churchill came to Egypt to have a look around for himself. Despite the recent checking of Rommel at the First Battle of El Alamein, Churchill yet again switched out his commanders. Auchinleck was rather unfairly replaced as C-in-C Middle East by Harold Alexander, while Ritchie was replaced as Eight Army commander by General Gott.

Gott, however, was shot down by two Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighters, then strafed and killed as he tried to help others out the wreckage. Next in line, almost by mischance, just happened to be a bloke named Bernard Law Montgomery. History would never be the same.

While Montgomery undoubtedly inherited a great defensive position and reinforced Eighth Army from Auchinleck, “Monty” also went about restoring his army’s cohesion and esprit de corps. After all, this army had been under six commanders in two years, constantly reorganized, and pummelled repeatedly by an army one-third its size. This army needed to find its confidence, and through hard training and discipline, Monty gave them exactly that.

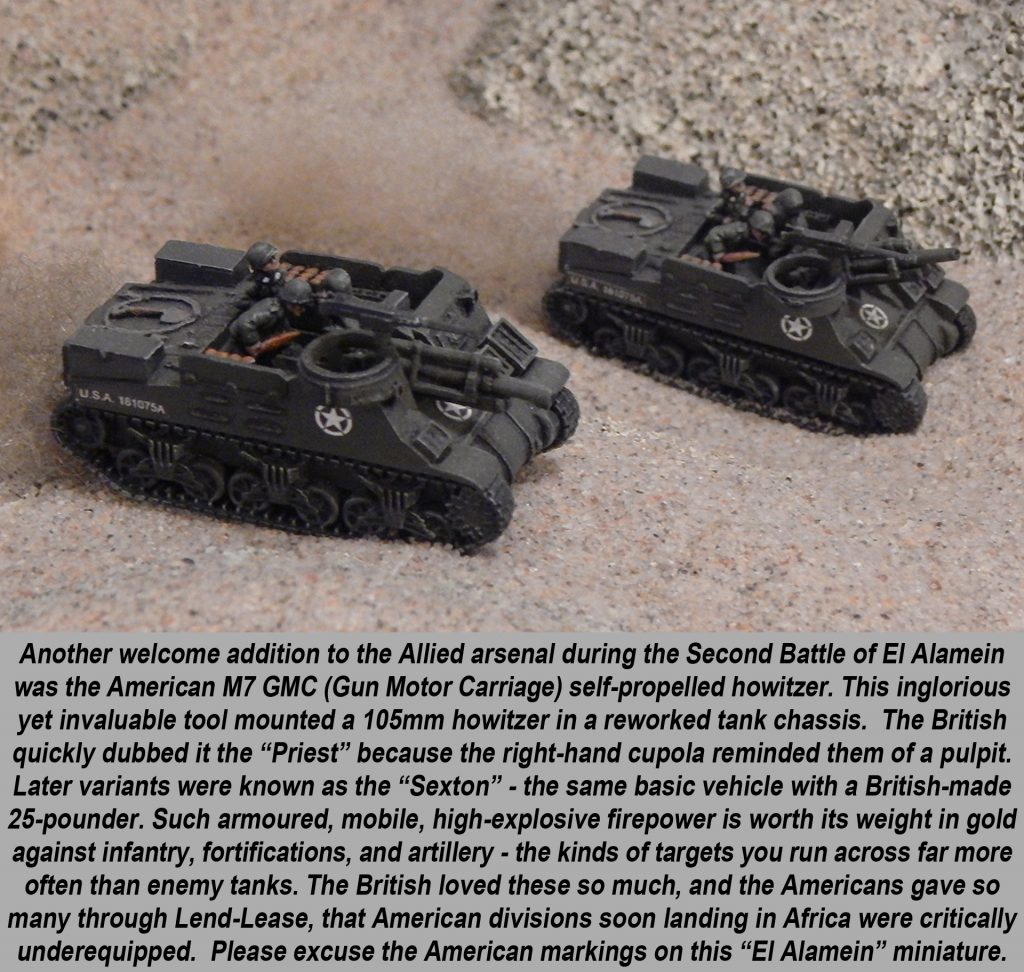

Meanwhile, the exhausted, ill-supplied, and terribly exposed Panzerarmee Afrika tried one last time to break Eighth Army’s line at the Battle of Alam Halfa. Again the Germans were defeated, further strengthening Eight Army’s resolve. Furthermore, a massive new convoy had just arrived from England, and the British took delivery of hundreds of their new “wonder weapons,” the American Sherman tank.

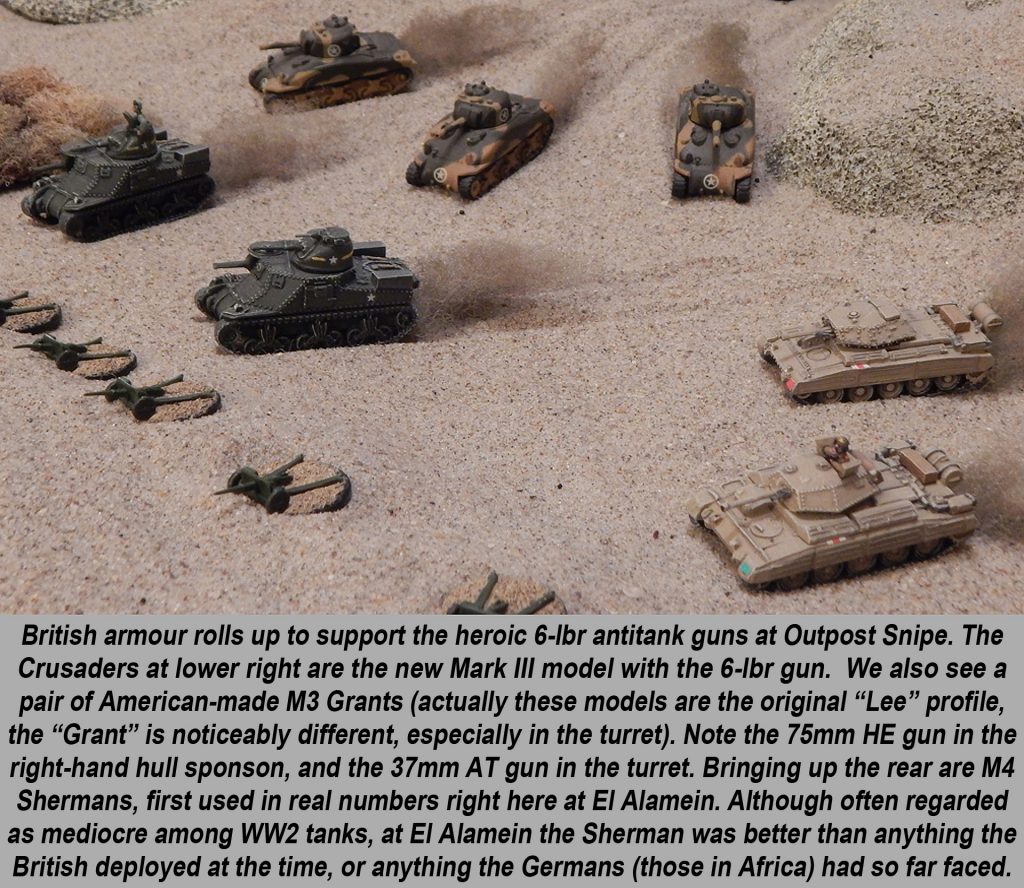

The Sherman gets kind of a “bad rap,” and through much of its operational history, deservedly so. But right at this moment and this place, the Sherman was an “alpha predator” killer. This isn’t Russia, remember, and there are no Tigers in Africa yet. Even up-gunned PzKpfwIVs are rare. On this one battlefield, the Sherman is actually a beast.

Another of Montgomery’s better traits was that he would not be pushed around by Churchill. Constantly Churchill ordered British generals into premature attacks that came to predictable disaster (then Churchill would fire the hapless commander). Monty would have none of it. Despite the incessant pressure, he meticulously trained, reequipped, and reorganized his Eighth Army. He would attack only when he and his men were ready.

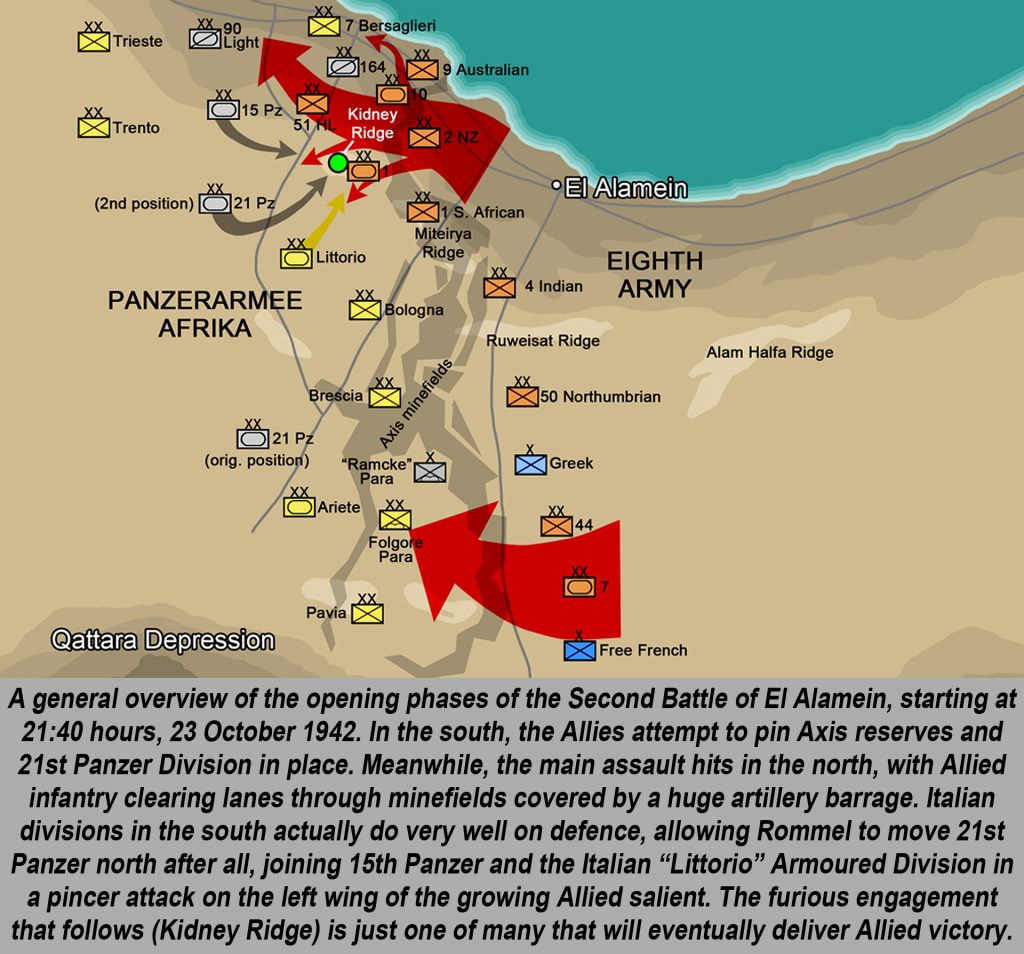

Thus, when Eighth Army finally hit Panzerarmee Afrika on October 23, 1942, it did so with the force of a thunderbolt. The artillery barrage was horrific, some sources claim it was the biggest single barrage outside of Russia since 1918. But the Germans and Italians held out. After all, just as the Alamein battlefield had been a great defensive position for the Allies, so it was for Panzerarmee Afrika now that the positions were reversed.

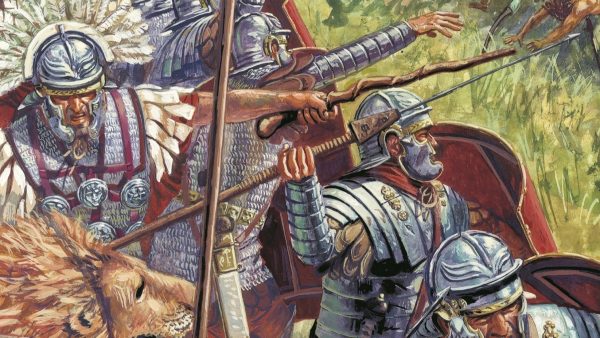

Behind this massive artillery barrage, Allied infantry delicately cleared lanes in the sprawling minefields (the operation was ironically code-named “Lightfoot”), through which British armour was intended to strike. It didn’t work at first. Axis minefields were too deep, Italian infantry were too stubborn, and German 88s were just too accurate. After four days, however, the Allies steadily bent and eventually cracked the Axis line in the north.

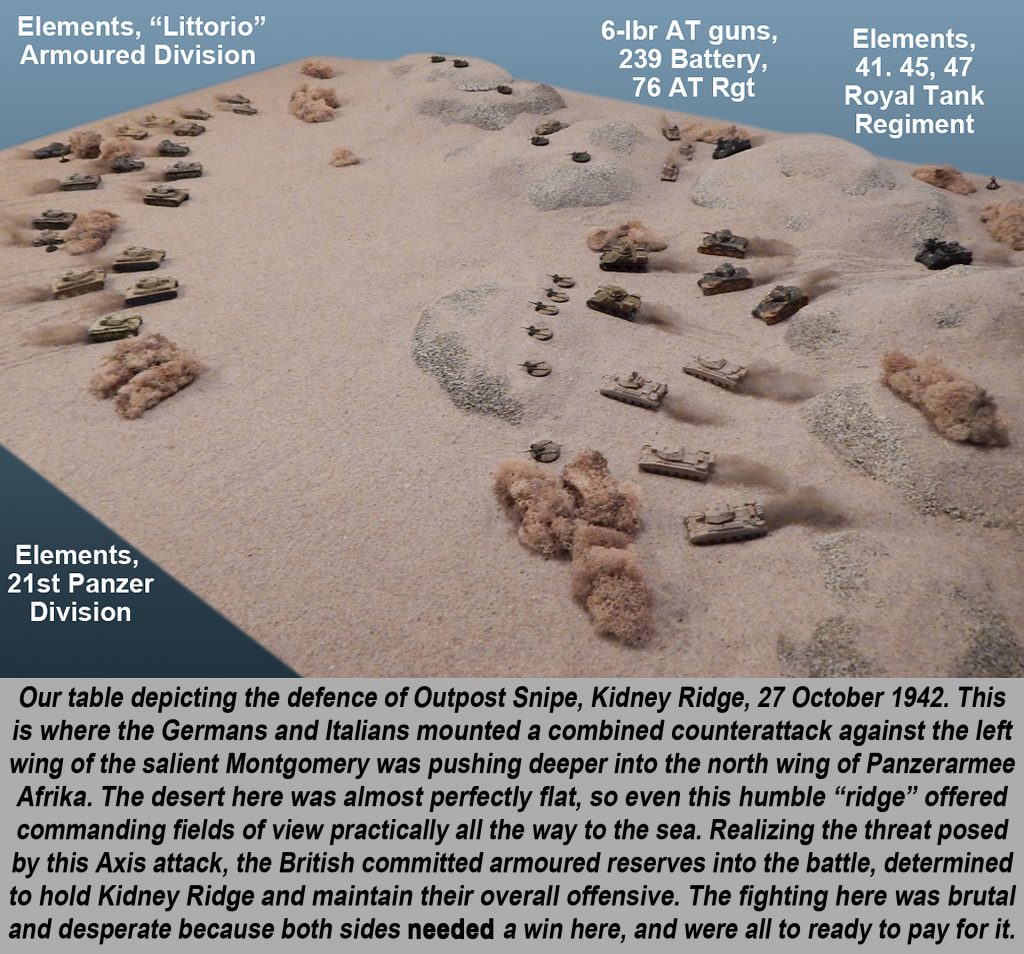

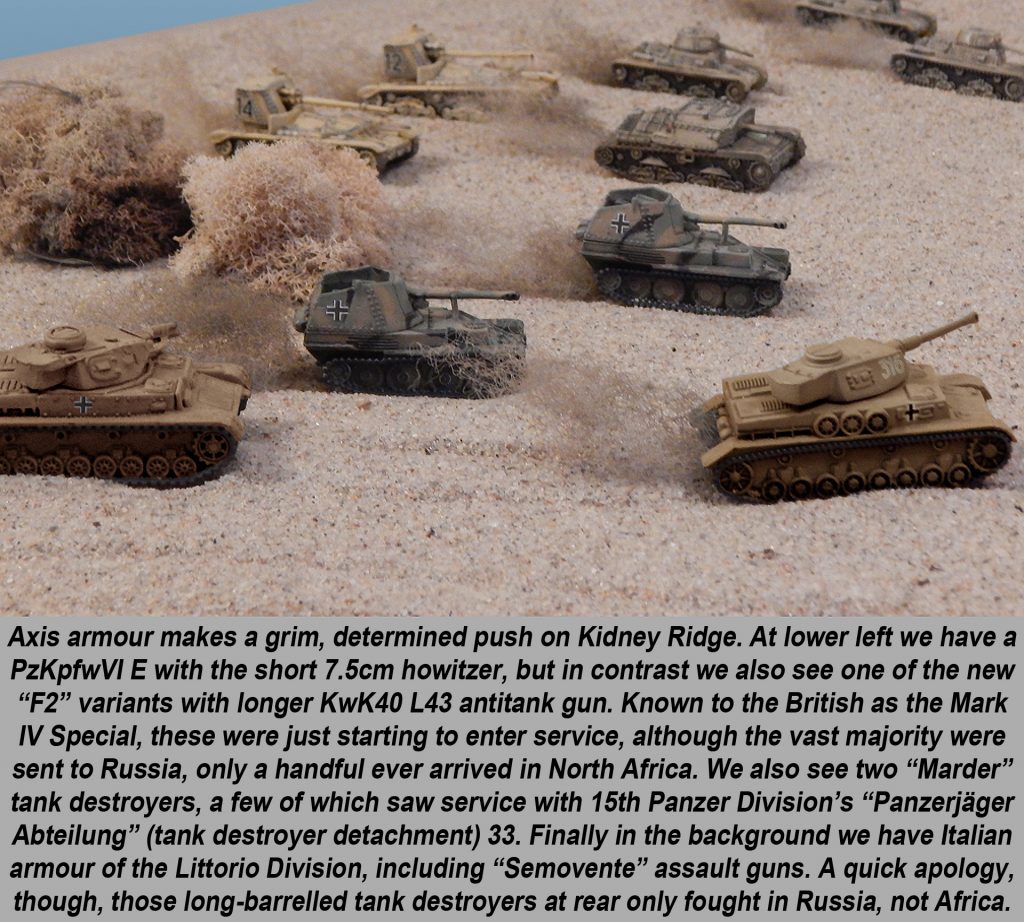

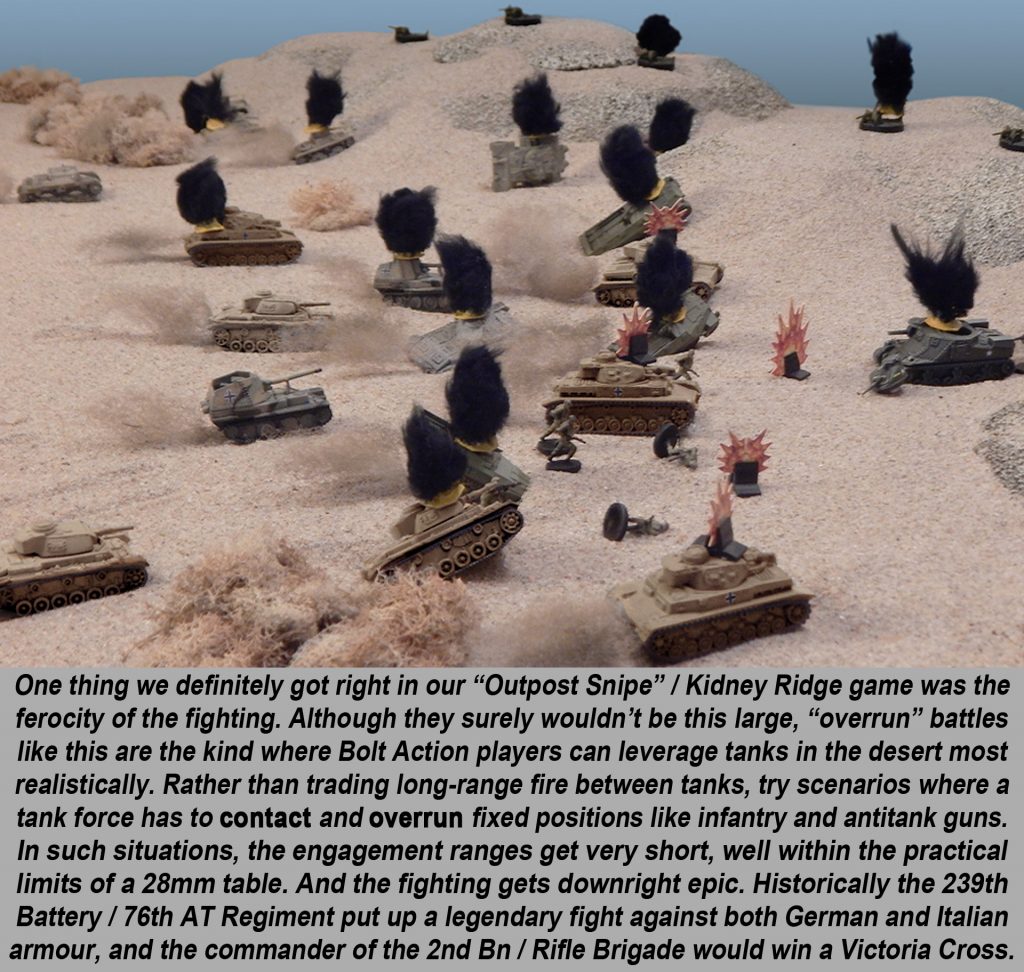

Frantic to contain this threat, Rommel hurled his three heaviest divisions (15th Panzer, 21st Panzer, and Italian “Littorio” Armoured) into a pincer assault on the flank of the Allied salient, which was anchored on a very modest “hill” called Kidney Ridge. Both sides knew what defeat would mean here, and accordingly, the battle at Kidney Ridge was savage, desperate, heroic, and extremely bloody.

In the end, the British at Kidney Ridge held. The Allied drive into Rommel’s northern wing was secure, and Panzerarmee Afrika had expended the very last of its strength. Montgomery reorganized and hit the Axis again with “Operation Supercharge,” which finally shattered Rommel’s defences.

Utterly broken, the Germans began a retreat all the way out of Egypt, all the way across Libya, and eventually all the way to the Tunisian border. So starved was the Axis for fuel that Rommel could only evacuate his German units, tens of thousands of Italians were simply abandoned to be captured by the Allies. The tide had turned, this time for good. The mythical aura of the “Afrika Korps” and the “Desert Fox” were forever shattered.

As Winston Churchill remarked: “No, this is not the end. This is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps...the end of the beginning.”

Even worse for Rommel, entirely new Allied forces had landed behind his forces in Tunisia. These, of course, were the “Operation Torch” landings in the French colonies of Morocco and Algeria. Now the remnants of Panzerarmee Afrika would face not only British and Commonwealth forces, but for the first time, American forces as well.

Of course, the Germans would also be getting help. New units, new generals, and new tanks would all be pouring in, turning “Panzerarmee Afrika” into “Army Group Afrika.” Come back next week as this restored and recovered Axis force meets its new enemies for the final, climactic showdown in the Desert War.

Put your comments, questions, and feedback below, and tell us if you’re ready to get your boots in the sand with the rest of us!

Getting fired up for the Bolt Action Boot Camp yet?

"...reading their exploits sounds like the script to countless 60s and 70s action movies except that for these men, the adventure was all too real!"

"“No, this is not the end. This is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps...the end of the beginning.”"

![Perfect Historical Wargame Objectives! Victrix Treasures & More Reviewed [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2026/02/unboxing-victrix-treasures_-chests-_-market-stalls-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

Operation Lightfoot, it would have been better to call it operation certain death! I am in total admiration for the soldiers that walked into those minefields to clear a way, whilst all hell was breaking around and over them. There is a famous painting by Terence Cuneo that is of a section of engineers doing just this selfless task. It is very humbling to think of the sacrifices that they made.

Thanks for kicking us off, @brucelea!

Indeed this was a crazy task carried out by the infantry and engineers of the 8th Army’s infantry divisions. I’ve said in interviews and articles that these lanes cut through minefields were 28 feet wide, through minefields in paces five miles deep. Slight generalization on my part . I think you asked at the last boot camp that his seemed like an awful lot, given the six-eight hours these men had to work with. Turns out that while yes … the minefields were in places five miles deep, and yes the lanes were 28 feet wide, and yes that had to do this all in that first night …

1) I don’t think the specific spots in the Axis minefields chosen for the assault were five miles deep. Recon had determined where the minefields were not as deep and I think these sectors were chosen in many cases. We have to remember that 8th Army’s engineers knew this ground defensively extremely well, as they’d just been laying their own minefields on defense here for three months (June-August 1942, First Alamein and Battle of Alam Halfa).

2) Honestly, they didn’t make it in many sectors. When the sun on that first morning came up not all these breakthroughs were fully developed and follow-up British tanks of 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions cane under fire of German antitank guns and artillery.

Terence Cuneo is indeed awesome. We use (and credit) his paintings several times I think through this and other series.

Oops – removing duplicate post

Nice one @oriskany nice one of you to give the Sherman its due, It s bad rep is not deserved, it was only really on the Western front that it had problems. Tankers that used it it Italy on the whole loved it because it worked! and of course it was king in the Far East.

Still like the classic Comment from a German infantry vet, on what he thought was the best tank, and hs said Sherman , when the interviewer queried it replied ‘It the only tank I ever saw’.

Thanks, @bobcockayne – indeed, when the Sherman first arrived at the front in North Africa in mid-late 1942 … it was a pretty serious threat. A lot of this comes down to timing and German military priorities.

1) Of course the Tiger and Panther hand’t come out yet (Panther would never see action in North Africa, naturally).

2) Most of the best German armor was still being sent to the East. I’m talking specifically about the vast majority of PzKpfw IV F/2s and Gs, even most of the PzKpfw IIIJ and Ls.

The PzKpfw IV “Special” and Grant took center stage at Alam Halfa Ridge (Aug-Sept 42), but the available numbers of PzKpfw IV were very very small. Then comes 2nd Alamein, where we see the Grant largely superseded in British service by the new M4 Sherman.

Good God, yes. In the Far East the M3 Lee/Grant was still a beast in the China / Burma / India theater well into 1945. The Japanese could do little against it, much less a Sherman. 😀

The case has been made that the Sherman’s good performance in North Africa was almost a bad thing long term, as it convinced American officers, crew, and industry that the Sherman was “good enough” to spearhead the Allied invasions into mainland Europe. New tank / tank destroyer development was never really prioritized like it should have been.

Once the PzKpfw IV Gs and Hs start to show up, much less the Panther (I’m leaving the Tiger off the list because propaganda aside, it was never numerous enough to actually be a factor in the large scale picture) … the Sherman found itself in big, big trouble.

Great article @oriskany. I remember reading that the second battle of El Alamein, was basically a WW1 western front battle in the dessert. Massive artillery barrage, infantry going forward to clear the way, tanks for exploiting a gap – would this be correct from your POV?

Absolutely, @tobymagill . At least the opening hours of Second Alamein could be thus characterized, with a massive nighttime artillery barrage, infantry pressing toward Italian and German trenches, trying to open lanes in minefields and take first enemy entrenchments.

The idea was to open routes through which follow-on armor of 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions could attack when the sun rose.

Didn’t quite work, which is what leads to Operation Lightfoot’s overall failure, and thus Monty’s second try with Operation Supercharge.

Many of these smaller engagements of which Second Alamein was comprised would remain infantry based and largely positional in nature, leading to further comparisons to WW1 engagements. It was straight-up frontal pressure, what Montgomery called “the Crumbling Phase” of his plan.

But once the sun came up on that first day, British armoured spearheads were up against German antitank guns, and where they managed to break through, they were counterattacked by elements of first 15th Panzer, and later 21st Panzer as well (after British 7th Armoured failed to really pin down 21st Panzer In the south). Of course 7th Armoured would be redeployed to the north to help with Operation Supercharge, making the battle even more mobile.

So while certainly true in many areas of Second Alamein, the WW1 “static, positional battle” analogy isn’t universal across the whole battlefield, and doesn’t last the whole time.

A very good one.

The first thing that caught my eye was the first map. I read through the divisions included in the Allied defence line and I read … Greek! I didn´t know the “Free Greek” also fought against the Germans just like the Free French. Was it just infantry or did they also use American, British or even Soviet heavier weapons? I´m quite sure they didn´t bring their heavy gear with them from Greece. I know they had some. There are pictures about the Balkan campaign where a Greek artillery piece is set up to defeat the Italians in the mountains of Albania (or something)

.

Second thing I noticed was the LRDG on the picture looks almost as good as @oriskany ´s 28mm LRDG :-). By the way a splendid idea to deny the defender his first turn in the case of a surprise attack. Noted and stored for my own purposes. Do you have an idea for something similar to imitate a situation when, for instance, a German tank force unexpectingly meets a Russian Pakfront? Kursk in mind.

Third: I remember a documentary about El Alamein and the artillery barrage the British let rain down on the German positions. The wide open mouth of the British artillery man sreaming “FIRE” (I could almost tell whether he had all his teeth left). One of the British soldiers said he even felt with the Germans to a certain extent when he listened to the thunder and watched the lightning of the firing, imagining the effect of the massive shelling on the German positions and the men crouching in there.

I wish I would be able to come to one of the BoW bootcamps, alas I can´t, so I´ll be watching the live blog, comment as witty as possible and put some sand under my computer table to get the feeling of desert war at least a little.

Thanks and looking forward to the next one.

Indeed, @jemmy, a brigade of Free Greeks was attached to 50th Northumbrian Division (part of XIII Corps), along with a brigade of Free French.

Equipment seems to be British issue (76mm Stokes mortars, Bren carriers, 2-lbr ATGs, 25 lbr howitzers, etc.).

The following is from gregpanzerblitz.com, detailing the platoon/battery-based OOB for this brigade.

Yeah, the “skip first turn” surprise mechanic is an old scenario-designers trick. It’s great for equalizing imbalanced forces for asymmetrical wargames. What makes it tough for the situation you describe is that the “surprised” Germans aren’t on defense, they’re on attack. They HAVE to have a first turn in order to be moving in order to come within range of that PaK front.

This is where “hidden antitank” rules like those we see in FoW come in handy. Or “sketch map” hidden defenses (don’t put your hidden units on the table, but you have a sketch map of the table and you have to deploy your ATGs there … when they fire or are otherwise revealed is when you actually put the model on the table) or … if you’re really ambitious … true double blind scenarios (tough to do in miniatures but more feasible for hex and counter wargames).

The British artillery barrage before Second Alamein was indeed massive. Something like 900 guns in all. It was the largest artillery barrage seen in the west since 1918 (some say since 1918 period, but they’re forgetting the Eastern Front, I think).

AWESOME! Look forward to seeing you at the live stream! Scheduled for noon GMT – Friday Sept 14.

A great read @oriskany the best thing about the Barce raid is that this type of raid could be played for any troop from stone age to 40k making a great game.

Indeed @zorg – a classic “smash-’em-up” raid – the stuff Hollywood action movies are made of.

Outpost Snipe is an interesting scenario. The original plan was to establish two outposts North and South of Kidney Ridge on the night of the 26th of October, one called Snipe, the other Woodcock. The assault on both positions started with navigation errors by the British forces; at Woodcock, the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (also known as 60th Rifles) instead of dismounting to assault on foot from 500 yards away, as was the plan, blundered onto the German position while still aboard their transports. Realising it would be suicidal to try and dismount and organise his battalion in front of the German guns, Major Blundeel ordered his trucks and Bren carriers to charge, taken by surprise the German resistance was limited and only a few casualties were sustained before the Germans surrendered and six anti-tank guns were captured. One of the Regimental histories recorded; “It shows what can be done by surprise tactics, especially if the surprise is equally divided between friend and foe”.

At Snipe, the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade found their 1st Armoured Division maps didn’t match the 51st Highland Division maps that the artillery was using for their fire plan, so the battalion commander decided to advance to where the artillery had been shooting. The position they took up was about half a mile from where they were supposed to be, the location they deployed in was a shallow depression about 1000 by 400 yards that made ideal cover for the Infantry companies and the six pounder guns of the anti-tank company of the Rifle Brigade and the attached six pounders of the 239th Battery of the 76th Anti-tank Regiment, Royal Artillery. Not long after deploying, the Rifles discovered they were between two Axis tank leaguers; the XII Armoured Battalion of the Littorio Division, elements of 15th Panzer and Kampfgruppe Stiffelmayer.

C Company of the Rifle Brigade made a night assault on the Littorio position from their Bren Carriers, they were equipped (completely unauthorised) with captured Axis machine guns and Vickers K guns looted from RAF wrecks. They destroyed a fuel bowser and two trucks for the loss of one carrier.

From before dawn until dusk the Snipe position was repeatedly assaulted by Axis armour, the Shermans of the 24th Armoured Brigade intervened when they crossed Kidney ridge, but they could not tell where the British positions were so they opened fire at the concentration of German armour, unfortunately, many of their shells hit the Rifle Brigade positions. The two units were not on the same radio frequency so the Rifles couldn’t call off the shelling from the Shermans, a Bren Carrier was sent out to warn the 24th, but only one squadron ceased fire. After some time the Shermans advanced into Snipe, but were too tall to take advantage of the available cover and the German anti-tank fire inflicted several losses. After seven Shermans were knocked out, the 24th retired to the East of Kidney Ridge.

Thanks to outstanding leadership from the officers and NCOs and the courage of the unit, the Rifle Brigade fought off all comers for the rest of the day, inflicting losses on the 15th Panzer, Littorio and the 21st Panzer Divisions that Rommel could ill afford as well as frustrating his efforts to destroy the 1st Armoured Division.

The Commander, Lieutenant -Colonel Victor Buller-Turner was awarded the VC, Sargeant Calistan was also nominated for a VC, but was awarded the DCM, other DCMs DSOs and MMs were awarded throughout the unit.

The authors Bierman & Smith summarised the battle at Snipe:

“Snipe was one of the turning points of the second Battle of El Alamein. Rommel became convinced that Montgomery was trying to break out from the salient around Kidney Ridge and squandered his precious armour trying to prevent it. It was a wrong move”.

Okay, @damon – I can finally get to a proper reply on this deserving post. 😀

Indeed, Snipe / Kidney Ridge / Hill 29 (taken all together) is an amazing episode in Second Alamein, one which I tried not only in Battlegroup (as seen above) but in much more detail via Panzer Leader / Brian Train’s Desert Leader series.

The scenario I designed for this:

DESERT LEADER SITUATION 37

KIDNEY RIDGE COUNTER ATTACK

THIRD ALAMEIN, 23 October 1942

Needless to say, as soon as Rommel got word that the British had finally launched their long-dreaded attack on the Alamein line, he immediately started hopping planes to get back to the front as quickly as possible. It was a good thing he did, because his replacement commander of Panzerarmee Afrika, General Georg Stumme, was already a casualty. He’d been up front observing the British advance when his staff car came under machine gun fire. As he crouched for cover on the running board and the car sped off, he suffered a fatal heart attack. He fell off and died in the desert, for several hours no one even knew what had happened to him.

Although the Italians were fighting well in the south, against XXX Corps’ advance in the north they were running faster than the British could advance. General von Thoma (taking command after Stumme’s disappearance) threw in German units to plug the breaches, especially 8th Panzer Regiment of the 15th Panzer Division and elements of the 164th Light Division. Fighting raged throughout October 24, with German units redeploying over and over, holding the fine together with their fingernails. On October 25, X Corps’ 10th Armoured Division made a shove for Mateiriya Ridge, but took heavy losses to German 88s. To the south, the Folgore Parachute Division continued to hold out well, even launching some counterattacks to retake lost ground against XIII Corps’ 7th Armoured. But there was no decisive, large-scale Axis armored counterattack, and when Rommel reached the front around midnight on October 25, he was furiously demanding to know why. Allied air attacks were just part of the reason, another was the fact that Stumme hadn’t been hoarding fuel quite as fanatically as Rommel had been, and the Panzerarmee’s mobile formations were already desperately short.

At least Rommel wasn’t alone in his grief. Monty had his share of headaches as well. His Operation “Lightfoot” had clearly failed to reach its initial objectives for the first day. Even now the “Oxalic Line” hadn’t been reached in some places. German minefields were even deeper than Allied intelligence had feared, and still the British didn’t have the prescribed two open lanes through XXX Corps’ attack sector. Thus, X Corps was being committed to help crack open the break they were supposed to blitz through and exploit, a fact that made X Corps’ commander, Lieutenant-General Herbert Lumsden, livid almost to the point of insubordination. It got to the point where Monty had to call a meeting mid-battle and personally straighten the man out. One can almost certainly see Lumsden’s point, though. The minefield lanes that were supposed to be his superhighways into the German rear were still not completely open, and even if they were, they opened up into the shadows of high ground the German guns still dominated.

This high ground can be roughly described as three terrain features, running from northwest to southeast. To the northwest was Hill 29, then “Kidney Ridge,” then Mateiriya Ridge to the southeast. The Germans fought throughout all of October 26 to hold these positions, but Allied numbers, air power, and Axis supply shortages were just too much. The Italian Littorio armored division, the 164th Light Division, and 15th Panzer in particular suffered heavy losses trying to hold this ground. Elsewhere on October 26, Rommel was making the tough choice to largely abandon the battle in the south and invest a frightening portion of his remaining fuel reserve to start bring mobile units northward, especially 21st Panzer. Clearly, if Rommel wanted to stop Monty’s main push and prevent him from cutting Rommel’s only remaining supply route (the coastal road), a showdown in the north was coming.

Monty, meanwhile, was drawing the same conclusions. He was getting ready for a new push of his own in the Hill 129-Kidney-Mateiriya Ridge sector, but as luck would have it, Rommel beat him to the punch. A massive two-pronged mixed-arms pincer hit this area on October 27, with the 90th Light and what remained of the 15th Panzer crashing down on Hill 129 from the northwest, and the 21st Panzer and Littorio divisions slashing up against Kidney Ridge from the southwest. Rommel supported the offensive with every artillery piece he could get into position, and even Kesselring threw every available aircraft into the effort. This would be Rommel’s last significant throw of the dice, setting up one of the most savagely-fought individual engagements of the Alamein battle.

A careful look at the map shows why this fight in particular was so nasty. With the desert being so flat, even the smallest lump of high ground gives its possessor a huge advantage in dominating the surrounding terrain. Whoever held these scraps of high ground could range artillery across half the Alamein battlefield, perhaps all way up to the sea. He who held the high ground held coastal highway, and thus the battlefield. Both Monty and Rommel had picked this area for their major efforts on October 27, and both pulling mobile formations off their southern lines to reinforce this critical sector (Monty was already pulling 7th Armoured up just as Rommel was pulling up 21st Panzer). “It is a fact of war,” Rommel wrote his wife, “that the most insignificant stretch of ground can assume deadly importance, heaps of sand which, in peacetime, even the poorest Arab would not bother his head about.” Montgomery would have agreed. Before the battle had kicked off, he’d left his men with no illusions that the first phase of Alamein would be a “killing match” perhaps twelve days long. Monty was a man who chose his words carefully, and in this case is prediction would be sadly prophetic.

The attack got underway with a strong showing by the Luftwaffe. Kesselring kept his word, if nothing else. Unfortunately, the Desert Air Force made a showing stronger still. Kittihawks and Hurricanes went wild on the Stukas, what few managed to get through were largely neutralized by very strong Allied antiaircraft fire. Then the Allied fighter-bombers went after the 21st Panzer, which suffered no less than eleven major air attacks that day. Even the Americans were involved, with about 12% of the day’s sorties flown by their twin-engine B-25 Mitchells, hammering behind the lines at Rommel’s already-disintegrating supply and communications network.

Ground fighting started early along Kidney Ridge and Hill 129, and seems to have lasted all day. Here, British sources are particularly detailed because of the legendary story of “Outpost Snipe,” defended by the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade and Battery 239 of the 76th Antitank Regiment. In a heroic day’s fighting in which all but one of the tiny unit’s 6-pounder antitank guns were knocked out, the battalion commander (Lt. Colonel Victor Baller Turner) won the Victoria’s Cross and several other men in the battalion won Distinguished Conduct Medals, Military Crosses, and Military Medals. For the historical wargamer, this results in a very well-documented record of the day’s fighting, if one remembers that some of these recreations lay the “King and Country” on a little thick. One map featured in WWII History Magazine gives the location and bearing of each individual gun, as well as the wreck locations of each individual German and Italian tank.

Although fighting around Outpost Snipe seems to have started as early as 03:00 hours and lasted intermittently until practically until dark, Rommel’s main shove against the overall Kidney Ridge position started closer to 15:00 that afternoon. This is the specific hour well be recreating in Situation 37, concentrating on the southern of Rommel’s attack, where about half the 21st Panzer and the rump of the Littorio Division struck northeast into the underside of Kidney Ridge. Looking at the board layout, we can see where the ridges cluster together to give this general impression (note how the boards are angled slightly to give more of a “northeast” impression for the Axis attack). The Axis air units have already largely failed to make an impression on the Allied position (note there are no Axis air units included) and the Allied air units are now free to engage ground targets (although certainly not at full strength, most Allied aircraft are assumed to be still engaged with the Luftwaffe or headed back to base to rearm).

As we know historically, the 24th Armoured Brigade (part of the 10th Armoured Division) is deployed to the southeast, while the 7th Motor Brigade (part of the 1st Armoured Division) is deployed to the northwest. The game starts out with the Italian Littorio division already engaged, represented at not quite full strength because of the day’s fighting, as well as the pervasive Axis supply and maintenance problems at this stage in the Alamein campaign. The 21st Panzer is represented at about half strength, because this is what Rommel gave Major General von Radnow to conduct his part of the attack, along with at least half the Panzeramee Afrika artillery. Note that this is represented in the game as slightly understrength because by now Rommel’s artillery was almost exclusively armed with captured British pieces, and even for these, ammunition was running desperately short.

Accounts from both sides portray the fighting as horrendous. Even British writers, who may be tempted to embellish their heroes’ performance, leave the reader in no doubt as to the determination on both sides. Note how the scenario doesn’t care how many units are killed, this is a “hit-and-stay” battle where victory is determined by who has the greater remaining weight on the key ground.

Note the British IPs and their special setup rules. This is meant to represent the historical locations of Outpost Snipe and Outpost Woodcock, basically large “bowls” in the ground that made ideal firing positions for low-silhouette 6-ponders. Although players aren’t mandated to do so, it might be neat to deploy two or three 6-pounder counters in each of these, along with a handful of rifle, MG, Bren, and Jeep counters in these positions. These would represent the 2nd Battalion / Rifle Brigade and 239 Battery (Outpost Snipe) and 2nd Battalion / King’s Royal Rifle Corps (Outpost Woodcock). Just remember that these valiant units took losses that would have easily been considered “unit destroyed” in the Panzer Leader CRT, so don’t be too depressed (or surprised) when these units are wiped off the map.

@oriskany, that looks like an interesting scenario, hex and counter definitely has an appeal.

For Bolt Action I think the night attack by C company against the Littorio leaguer might make an interesting and different ‘zoom in’ to the Snipe action.

I would agree with that, @damon – night actions are almost all infantry-based (Bolt Action friendly) and shorter ranged for small arms (again, Bolt Action friendly).

Daylight action at Snipe … i.e., 6-pounders against German and Italian armor … not so much. 😀

We built and refought Snipe twice at games shows around 20 years ago using Skytrex 1/200th models and the Panzer rule system, both times got pretty simulilar results.

A friend still has the tiles and about an inch of limestone dust from a quarry in his loft.

1:200 sounds like a good scale for this battle @bobcockayne , given the engagement ranges of 6lbr, 5.0 cm, and 7.5cm direct fire howitzer weapons in use (plus whatever the Italians had as well).

I just like it because it was a “kitchen sink” kind of a battle, the kind that historically happens very infrequently. Infantry, armour, direct fire artillery, support indirect (off board) artillery, and three nations on top of that (assuming you zoom out just a little on the Panzer Leader scale).

Oh, one thing, though …

ERRATA: One of the pictures in the article above depicts 90mm Italian Semovente tank destroyers. Turns out these fought only in Russia, and were not utilized in the Western Desert. Apologies. 😐

@oriskany dont think you have to apologise had a look at the token on your picture under the magnifier, thought the silhouette looked wrong for a 90mm and bit at bottom says L40.

1/200th was a simple hexes to inchs conversion for Panzer’s 88, sham they never updated lists of 88 when they re-did at minatures game, though they are a very tank orientated set of rules and infantry rules are basic, though trying to spot the little buggers form tanks is fun…….not!

Thanks, @bobcockayne – I was actually looking at the photo in the article – that has some of the Semovente assault guns in the background with the Mod 39/90 Canone AA guns on the back (big yellow suckers with “12” and “14” on them.

Yes, my Panzer Leader games are usually more accurate than my miniature games. 😀

@oriskany realise you might be on about above after posted, thought you had already apologised for that. If nothing else you have them pointing the right way (on going joke about club member who had a WW2 battlewagon the wrong way round even though there was a wake at back).

@bobcockayne – “thought you had already apologised for that.” – I may have. There are a lot of threads flying around and some of these photos are three years old. 🙂 But yes … at least we have them pointing the right way. Not too hard when you see the size of that gun! 😀

In my defense, these Semovente 39/90s were also included in the original Desert Leader Panzer Leader set … so at least I’m not alone in this.

@oriskany did they get them mixed up with the truck mounted version that may have appeared at end of Desert war?

Errp … nope, I was wrong again. Semovente 39/90s were NOT in the original Brian Train Desert Leader set. He knew better, I did not.

Man, I cannot win with these Semoventes. They are my historical kryptonite! 🙁

Another interesting read

Thanks very much, @rasmus! 😀

Awesome article can’t wait to see all the cool bootcamp content still to come.

A great book for anyone wanting to know more about/make wargaming scenarios for the Desert Special Ops is SAS Ghost Patrol. It’s about Operation Caravan and the monumental work that went into it. The British created SIG (Special Interrogation Group) which were German’s in the British army who posed as German Soldiers, which I had never heard of before reading the book, then used them to drive 80 SAS/Commandos into Tobruk in three trucks in broad daylight. They knew they had been spotted and Tobruk HQ knew they were coming but the message didn’t get taken seriously and wasn’t passed low enough in the chain of command eg. Company Commanders knew what to look for but Squad Sergeants and Sentries had no idea..

They got stopped at a roadblock where a Guard asked them the password which they didn’t have but they had last month’s so they let them pass, the next roadblock refused them so they went back to the first and asked them what it was. They had no clue so had to go inside for a few drinks and radio headquarters for the password. If it was a movie people wouldn’t believe it.

Those raids would be perfect for Bolt Action, LRDG Jeeps screaming through the Desert coming up against some Italians in trucks with a Light Tank in support. The First SIG Operation would be really cool to play, they snuck some French SAS onto a German Airfield but were betrayed by one of their German POW Instructors who alerted the Germans and got most of them killed. Start the game with some SAS in a few trucks and have a Platoon of Germans ambush them, escape and cause some damage while they’re at it.

My favourite anecdote from the book is when the SIG soldiers infiltrate a German Camp to learn how to act and talk like a DAK Soldier. A few of the men test out their fake credentials and go get a few Months pay and it works.

Really loving these articles.

Thanks very much, @elessar2590 –

Operation Caravan is indeed amazing. There will be lots of this and other stories / episodes covered during the boot camp interviews / live blog, in our “Tales of the Desert” series. Repairing alternator mounts with sand and chewing gum, burying fuel and water and somehow finding it again six months later, meeting tiny little biplanes for resupply out in some remote stretch of desert even Google Earth can’t find ( 😀 ), the one guy who was thought lost until he showed up 10 days later at a rendezvous point, having walking 210 miles across open Libyan desert, etc. …

Your story sounds a lot like the LRDG patrols getting into Barca airfield, they’d been spotted from the air (Italian Air Force) but somehow someone didn’t get the message. Other Italian units on the ground DID know, just didn’t expect them to simply drive straight through the front gate of the airfield. . Then the LRDG / SAS drive right past an Italian patrol going out to find them (at night), but because they’re not expecting the LRDG / SAS to use this main road so brazenly (literally just driving straight to the airfield like they were trying to catch a commercial flight) , the two vehicle convoys basically waved to each other as they passed.

I totally agree about Bolt Action’s suitability for this. Bolt Action’s characteristics, including some I sometimes complain about, are all a PERFECT fit for this kind of action. Small scale battles. Infantry action. Not many rifles, but mostly SMGs, perfect for 28mm tables. Heroic troops, so the “cinematic feel” of the game somehow becomes appropriate even for the most dour of “history-perfect” grognards.

Probably why the very day I heard about this boot camp, I went to Warlord and bought two of their LRDG trucks and some of their SAS / LRDG infantry. 😀

Great article and photos. I love the “pink” jeeps and trucks!

Thanks, @gladesrunner – turns out that was only one of many color schemes used by these units. For some reason, that particular shade of pink vanishes into the desert sand … when viewed from the air. I’ve also read accounts where it was used because dawn and dusk were considered the most dangerous times for detection. In any event, for these guys it was all about hiding in plain sight (not much cover in the Libyan Sand Sea), striking out of nowhere, then vanishing just as quickly.

Great detail in there being ore than one Battle of El Alamein. Strange to think that Montgomery was actually not the first choice to lead this battle. Any predictions on how this might have turned out if Gott had been in command instead?

Thanks, @pslemon –

Gott was a very solid officer with years of desert warfare experience. As commander of XIII Corps, he led the “original” corps in Eighth Army what had originally grown from the WDF (Western Desert Force), then the XIII Corps, then XIII and XXX Corps, and finally XIII, XXX, and X Corps.

So he certainly had the technical, tactical and moral capabilities to lead well.

The issue is, was he TOO experienced – i.e., he’d seen all these Eight Army defeats at the hands of Rommel and was too accustomed to doing things the old way? I honestly don’t know. But as much as I feel Montgomery needs to share the credit for “his” victory at Alamein, I also feel that the Eighth Army needed a fresh start with someone with a new, outside perspective.

Also, where I fully give Monty all the credit in the world is where he stands off Churchill and his pressure for immediate offensives. With Operation Brevity, Battleaxe, and even Crusader and the July

42 battles of First Alamein, Successive WDF / XIII Corps / Eighth Army commanders were pushed into premature action by Churchill and his political concerns.

Monty basically told Churchill to settle down, take a breath, and Monty would attack only when he was damned good and ready. Honestly this is the most decisive aspect of the whole Alamein series of battles, it game Monty the time he needed to reforge Eighth Army, which in turn gives him the Eighth Army he needs to the bitter, head-to-head “crumbling” action we see in the battle.

Would Gott have been able to do the same thing with Churchill?

Honestly, I don’t know.