Behind The Board Games: Sophie Williams, Needy Cat Games

March 21, 2019 by dracs

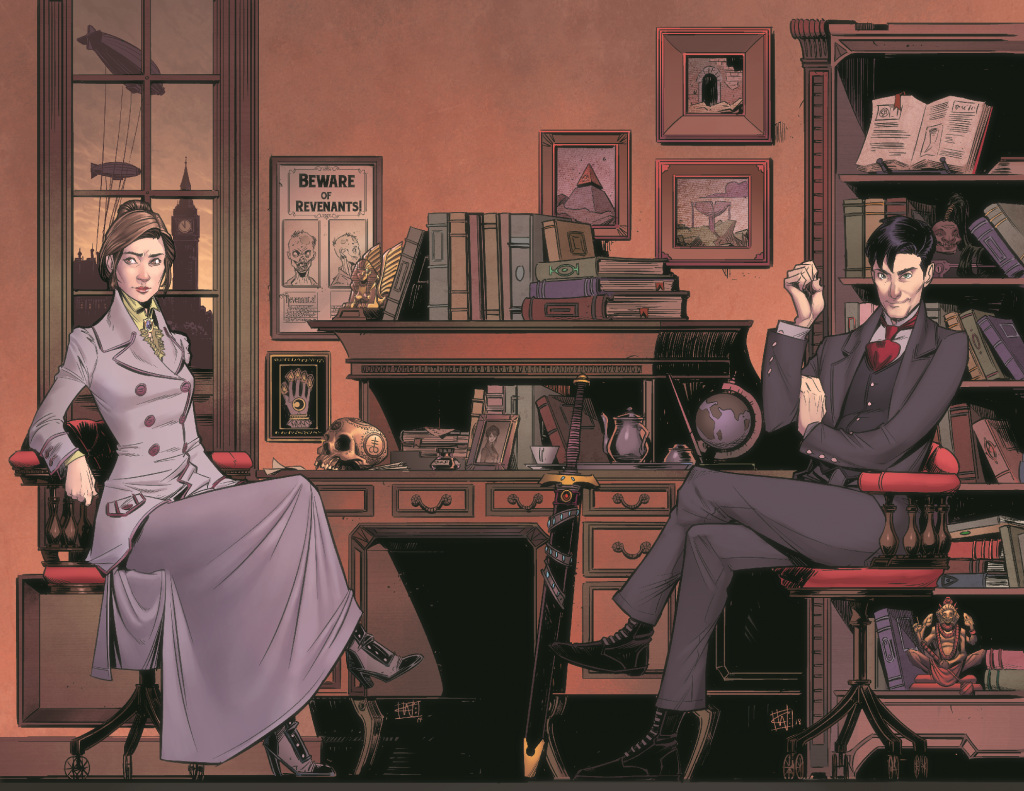

Sophie Williams has a long and storied career in tabletop gaming, starting off at Games Workshop and culminating in her current role as one half of the Nottingham-based tabletop design studio Needy Cat Games. She has worked on all manner of game titles, including Hellboy: The Board Game, Ancient Grudges: Bonefields, and the recently announced Newbury & Hobbes: The Curse of Menamhotep.

In this interview, she takes the time to answer Sam's questions on her experience in tabletop game design, as well as providing some insight into her design process.

Sam: How did you first get into tabletop gaming?

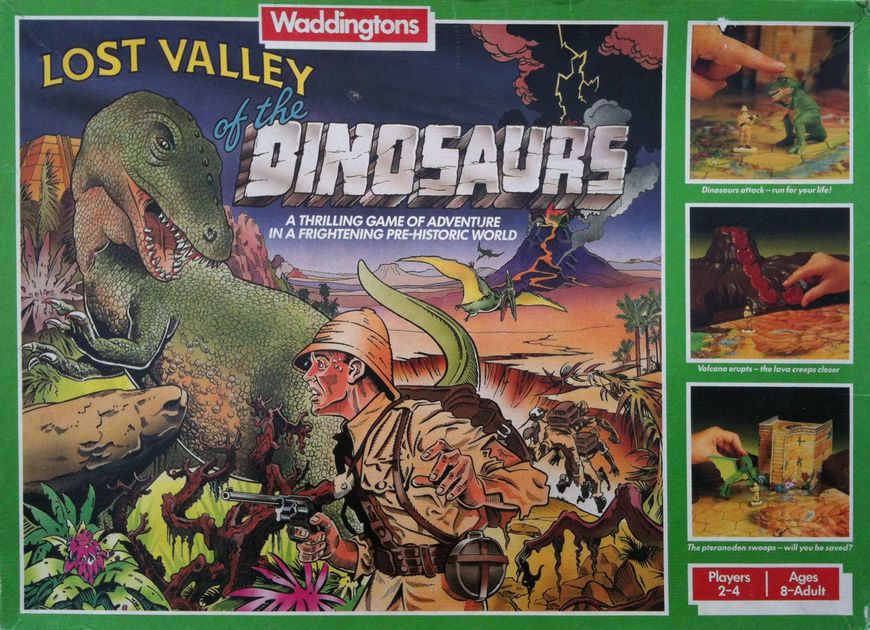

Sophie: As far back as I remember I've been involved in some kind of tabletop gaming – one of my strongest memories of being very little was playing with the lava pieces from my older brother's copy of Valley of the Lost Dinosaurs.

My eldest brother also had an awesome model of a skeletal mammoth holding prisoners. I have no idea what it was for, but he'd built and painted it and then, inevitably, it had fallen apart. I was fascinated by it and it wasn't long before I was getting into building and painting Warhammer miniatures in my teens.

I played D&D from about fifteen and discovered a wider world of gaming while at university, which is when I started playing Warhammer and Warhammer 40,000 properly.

A little while later, I got a job in the Games Workshop in Maidenhead and spent the next few years managing stores around the country. After that, it was a slippery slope into board gaming, because I was too busy with work to spend as much time painting armies. I think my first 'hobby' board game was Last Night on Earth, which is still an amazing game!

S: What are some of your favourite games? Do any of them inspire you in your approach to game design?

SW: I’m constantly discovering new games with amazing mechanics, so I find it incredibly difficult to settle on favourites. That said, one of my top games has to be Pandemic Legacy. I love the Legacy format. I rarely find the time to play any game I own more than a few times, let alone more than a dozen, but the storytelling element of Legacy games compels me to keep going back.

It also doesn’t hurt that the game is so beautifully designed, and introduces enough new stuff that you truly do get a different gaming experience every time. I've actually played through it twice, two years apart, and it was just as enjoyable the second time even though we already knew the plot twists!

I suppose this love of storytelling has really influenced my taste in games of late. I'm loving escape room style games such as EXIT and UNLOCK. Both are compelling and enjoyable but in completely different ways… but I can’t really explain why without spoilers!

I've also been playing through Stuffed Fables and Near and Far recently. Both games feature a storybook as the game board, which you play through over the course of a campaign. I really appreciate a game where all the parts of it feel beautifully crafted and these games both embody that. I think you can see the influences of Legacy and storytelling ideas in Hellboy: The Board Game.

Of course, there are plenty of other games I'm loving at the moment, too. Fog of Love is a really fascinating idea where there is no direct competitiveness. What you do does affect the other player, but your focus is on achieving your own goals… but at the same time, everything you do is linked. This was a real stand-out game in terms of innovation, and I’m really excited to see how it influences the next generation of games.

Then there are the staples I play loads because I love them. Ticket to Ride, Splendor and Sagrada are all regular visitors to my gaming table. They’re especially great to play with people who don't often play board games. Basically, I love games that feature interesting decisions, where there's more than one option to achieve the things you want. I try really hard to give players similar options in the games I work on. Almost all great games boil down to engaging choices, so I'm always pushing myself to try and create games that let people focus on choices rather than mechanics.

S: How did you make the leap from gamer to games designer?

SW: It's been a slow evolution over many years. I've done my fair share of GMing and I’ve written a decent number of roleplay campaigns. I wrote and ran a lot of store campaigns when I was at Games Workshop, and gradually started writing small mini-games using miniatures from other systems. I've also playtested a lot of games – when you live in the same house as James M. Hewitt, you can't get away with not!

Over time I got more and more engaged in rules development, as opposed to simply giving feedback on the games I had played. I dabbled more and more in writing rules and games and then finally, came on to join Needy Cat Games about six months after James went freelance. I’ve been designing games full time since then. It's been a busy eighteen months!

S: You’ve had a long and varied career in the tabletop gaming industry. What would you say are some of your career highlights?

SW: It would be easy to talk about the fact that I was the first woman retail manager for a Games Workshop in the UK – that was a big deal at the time and I was really proud of my achievements – but that was a long time ago and I've done a lot since then, so it feels like ancient history!

I think working on my first solo game last year was a big deal for me. It was a skirmish game for Macrocosm Miniatures called Ancient Grudges: Bonefields.

That was a massive high point because it enabled me to really confront my impostor syndrome. It's easy to allow that voice in your head to tell you that you're just basking in the light of others, but I was really proud of how the game came out. It proved to myself that I was a games designer in my own right.

Plus it's always a massive boost when people recognise me - which is happening more and more these days. It's a bit weird, but it's lovely.

S: What made you decide to step away and start Needy Cat?

SW: After being made redundant quite soon after returning to work from maternity leave, I felt pretty low and a bit rudderless. I've always struggled to pin down anything that I absolutely certainly definitely wanted to do as a career for the rest of my life.

So many people I know have always wanted to do a specific thing and were absolutely sure of it, but I've never had that and so I've always struggled with looking into the future and knowing where I'm going to end up. However, I eventually realised that the reason I never had that career goal was that I had been told time and again as I was growing up that being “a creative” wasn't really a career.

“It's great that you like drawing and writing, dear, but that's not a job, it's a hobby. You need to go and do something that's going to earn a wage!”

It was the same message at home and at college, so I did a degree that was a bit more grounded, even though it meant I never really fully got into it. Then that degree turned out to lead to very few jobs, and even fewer careers, so I just shelved all of those desires and set about trying to find something – anything – that would capture my attention.

The truth of the matter is, nothing ever really did, and that meant I've never really had a career, just a series of jobs where I did well for a year or so until I got bored out of my mind. I’ve been a retail manager, an employment advisor, an archaeologist, an art manager, a licensing liaison and plenty of other things, but through all of it, I just wanted a chance to be creative.

It got to a point where I realised I had to give it a go. If it didn't work, I'd not be any worse off, but feeling like I couldn't was making me miserable. And… here I am! I have no idea what the next step from here is, but it feels good to be here. And seeing my face on your list of Women to Watch was weird, but very gratifying.

S: How do you approach game design? Do you start with a mechanic first, or do you start with an idea of what the game is about?

SW: At Needy Cat, we have a theme-first design process. That means we always start out by thinking about theme and setting and the emotions we want the player to experience.

Why will this experience be fun? What decisions will be interesting in this setting? What kind of gaming experience do we want them to have? How can we bake the theme into the mechanics?

We'll do lots of idea boards during the early stages. We'll consume as much media about the subject matter as we can – we watch films, read books, read comics, listen to music, watch plays, do historical research. I recently spent several hours watching documentaries on YouTube about historical gunfights (Yes, that counted as work!).

We really dig around to find whatever fuel we can to fire our imaginations, then we start scribbling down ideas about what makes the theme fun, what the common tropes are, and how we might start to turn that into a game that evokes the appropriate ideas and feelings.

S: How do you go about taking a game from the first idea to finished product?

SW: We're super open about our design process. In fact, you can go to our website [link: www.needycatgames.com/design-process] and see a full breakdown of our design process and all the stages we go through to get to a final product. But I'll summarise here.

Bear in mind that most of our work is done with a client, such as Mantic Games for whom we did Hellboy: The Board Game. We do all the design work, but they add all the graphics and make it look beautiful, as well as dealing with manufacturers and distributors!

Anyway, our part of the process has the following stages.

Kick-off – we establish the needs of the client and what they want from the game.

R&D – we research and throw around ideas

Test Build – we design a very, very rough “test build” of the game, and build a scrappy prototype. This is a snapshot of gameplay, often with placeholder mechanics. It doesn’t have a start or an end. It’s a look at how a few minutes of play might be, and it's there to see the shape of the game. Does the process of playing through this tiny slice of the game FEEL right? We show this to the client and see if we’re on the right track.

Mechanical Draft – we write a functionally complete game, meaning you can play it from start to finish. It won’t be complete (for example, the Hellboy mechanical draft only had two Agents and one Case File) but it does need to showcase a full session of gameplay. It does not have to be polished, the rules can just be bullet points, and it can still have a few gaps and placeholders. Then we test it! We play games with people, on our own, making notes all the time. We iterate constantly, tweaking and testing. Over and over. (Play more games!) Then we keep tweaking. This process could go on forever, and it would if we didn’t have deadlines! The skill is in getting enough games in that you're happy with the outcome. (Note to publishers: if you squeeze deadlines, it's this bit of the process that will suffer, and the game will be underbaked.)

Full Draft – now that the game is designed, we start writing the rulebook. We also add complete scenarios, all characters, and any other twiddly bits. Then we test the complete game, including 'blind' playtests (where we give the complete game to a group who have never seen it before and see if they can play it from just reading the rulebook). We make copious notes, iterate and repeat until it’s absolutely perfect or until the deadline hits, whichever comes first. It’s never the first one, and it never will be.

Handover – We hand over the fully written game to the client. This is the toughest stage because the game will never be 100% finished in our eyes. There’s always more we could tweak, alter and amend. You can always refine one last thing or doodle around with one last bit, but you have to discipline yourself. There is a definite law of diminishing returns when refining a rule set and there's also burnout – if you never let it go, then you'll probably get sick of it! Deadlines are actually really helpful.

Amends – this is the last step, and the bit that people often forget to budget for (ourselves included). There are always tweaks and amends. Tiny things you missed, changes based on layout restrictions, feedback from editors or huge clangers you somehow catch just before it all goes to print, because you were playtesting it just one last time for 'fun'. It's just part of the process. It's not done until it's printed.

Phew! It seems easy when I write it down! Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn't. Sometimes you get caught in a cycle of Test Builds, none of them feeling quite *right*. Sometimes you sail into the Mechanical Build so quickly you have no idea how you got there. It's just the way of things. Having a system helps us drive forward with a project even when we're struggling, but it's far from infallible, and no two projects are ever the same.

S: Having worked on Hellboy, and now Newbury and Hobbes, what is it like to work on something with an established story, as opposed to an original IP?

SW: I love it! Having a world to play within and having boundaries and borders actually makes design easier in my opinion. Some of the most difficult projects I've worked on have been ones where the brief is just 'do anything'. In practice it rarely works like that – you come back with something and the response is all too often 'well, I didn't mean something like that'…

Working within the boundaries of an amazing IP gives you plenty of material to inform the direction of the game. It drives me to try and embody the feel of the setting, which then informs my decisions about what mechanics to use and when. It's also really inspiring. Working within the realms of an established IP, you feel like you're rolling around in someone’s creativity. It's really rewarding when people tell you that you've achieved what you set out to do, and represented that world appropriately.

S: What would be your dream game project to work on?

SW: I'll be honest, I think we're doing it almost exactly with Newbury and Hobbes: The Curse of Menamhotep. It ticks all my boxes. Strong story elements, interesting decision making, some surprises along the way for the players, amazingly talented artists, strong visuals and component quality, amazing IP. It's got all the goods.

It's why we couldn't turn it down when the opportunity arose! Also, we’re working directly with author George Mann, so we’re handling all the bits that normally come after our process. It's a bit scary doing something for yourself, but this is the most exciting project I've worked on so far and I cannot wait to see what everyone thinks of it!

S: Do you have any advice for anyone looking to get into the gaming industry, as a designer, artist, or in any other such field?

SW: There's a bit of a mantra I've developed when asked this before: Write more games. Play more games. Repeat. If you want to write games, play lots of games. Not just the stuff you always play; consume as much as you can. Board games, war games, computer games, storytelling games, roleplaying games, app games.

See the full spectrum of what’s out there. Then have a go at writing a game. Play it and test it and get it to the point where it’s good enough, then write another game. Keep going. Don't doodle away on one game over and over for ten years. Write a game and finish it, then write another, and another, then, guess what? Play some more games. Practice makes perfect.

The same principle can be applied to anything you want to get good at. Don't just consume exactly the same thing - go out and explore the whole world of what's available. If you're an artist, try lots of different types: drawing, painting, stencils, printmaking, digital art. Vary your output. Draw everything from small page fillers to epic battle scenes, loose sketches to finished portraits. Finish some pieces and then go out and experience more art. Go to exhibitions, but also watch poetry, read books, dance. Then draw more. Repeat.

Then, come and say hi! Get out there and find people who are already doing what you want to do, either in person or online. Get to know people in the industry. Talk to them, build relationships. We're a friendly bunch, scattered across the world, and we remember people who talk to us – especially if you're talented and passionate. Be open and friendly and engage with us, online or at events. Put yourself out there.

Accept that failure is part of learning. You won't get the job sometimes, but sometimes you will. In an industry where most of us are freelancers, we want to collaborate with people we know and trust. If we know you're easy to get along with, do quality work and are reliable, we'll ask for you when we need you. If all else fails, start a small design studio in the Midlands and name it after a pet. Good luck!

Which of Sophie's games are you most interested in?

"I'm always pushing myself to try and create games that let people focus on choices rather than mechanics."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"It's a bit scary doing something for yourself, but [Newbury & Hobbes] is the most exciting project I've worked on so far."

Supported by (Turn Off)

A great insight into the process 😀

some nice incites into the production process I think the hellboy game would be a great game to play

As someone who wants to break into the creative side of tabletop gaming someday, Sophie provides some really useful insights into the design process here.

My wife loved playing dinosaurs when she was younger and it’s what got her into games. She found Warhammer a bit to over the top but really loved the lord of the rings game and stuff like pandemic legacy

Love hearing the’behind the scenes’ journey stuff ?