Gaming The American War Of Independence Part One – The Shot Heard Round The World

April 4, 2016 by crew

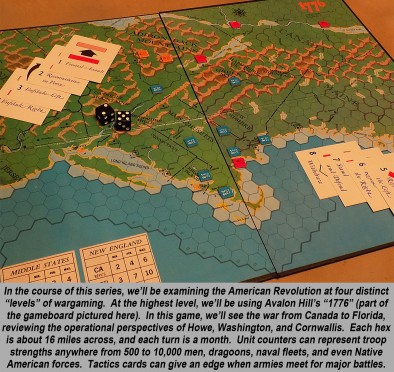

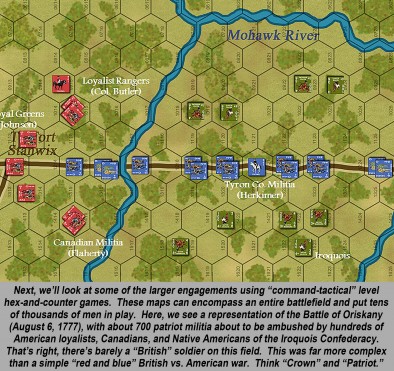

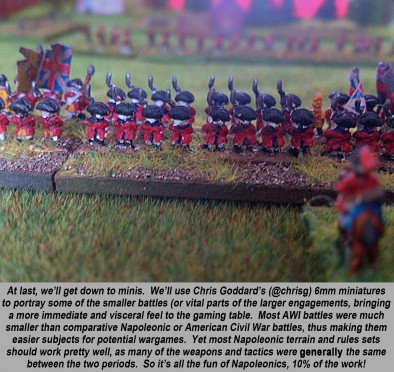

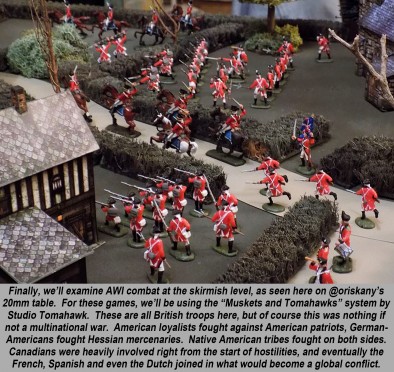

Welcome, Beasts of War, to a five-part article series presented by community members @oriskany and @chrisg. Our topic will be helping wargamers play their way through one of the most famous, yet misunderstood, wars in the last few centuries; The American Revolution (sometimes called the American War of Independence, or AWI).

Completely examining the causes, ideology and politics of the American Revolution would take fifty articles, and oceans of ink have already been spilled by authors far more eminent than us. Instead, we will focus strictly on the campaigns, battles, and conditions that should be understood to properly set up a game set in this conflict.

An Exercise In Perspective

Through the course of this series, we’ll be careful to remain objective. Many subscribers come from the UK and the US, after all. There’s plenty to be said on both sides, and we’ll pull no punches when it comes to drumming up a little friendly “transatlantic Beasts of War” rivalry. We’ll just make sure both views are represented.

Accordingly, Chris Goddard (BoW @chrisg), a true Yorkshire Englishman, will be writing his segments as seen by those loyal to the crown, His Majesty King George III. Meanwhile, James Johnson (BoW @oriskany) will take the role of the firebrand rebel, presenting from the perspective of patriots determined to bring forth their new nation.

An Overview For The Crown

The American Revolution, or War of Independence, or First Civil War, or whatever you choose to call it, has its roots long before the first shot was fired, and long before the Boston “Tea Party” or Boston “Massacre” you’ll hear these rebel colonials carry on so much about.

Some twenty years prior, the Crown had nobly “sorted out” a bitter and expensive war against the French of Canada and their Native American allies. Known as the French & Indian War, it was part of the global Seven Years War, which Britain had undertaken (in part) in defence of her rightful American colonies.

That war had cost a tremendous amount of money, and the Crown levied taxes to help pay a crushing war debt. It was only fair that the colonies that had been so bravely defended pay their fair share. Yet the American colonists steadfastly refused, raising quite the fuss about imagined “tyranny” and “lack of representation.”

Tensions mounted through the 1760s and early 1770s. Angry mobs attacked His Majesty’s troops in the streets of Boston, and when these men fired to protect themselves, these “Sons of Liberty” cried “massacre.” Later they’d attack our merchant ships in Boston harbour, their “Tea Party” little more than an act of organized vandalism.

All the while, the American colonists were the most free, and least-taxed subjects of His Majesty’s empire. But it wasn’t enough for them. Meanwhile, as unrest led inevitably to rebellion, our real enemies (France and Spain), seething for revenge from their disastrous defeat in the Seven Wars War, watched carefully and bided their time.

An Overview For The Patriots

Rarely in the course of history has one people tried so hard to avoid going to war with another. Leaving aside our most fervent hotheads (I’m looking at you, Samuel Adams), the absolute last thing Patriot leaders wanted was war with the British Empire. The prospect terrified us, and with good reason.

Great Britain was the most powerful nation on earth, and had just emerged triumphant from the Seven Years War. What did we have besides fowling rifles and squirrel guns? No navy, no treasury, no credit, no allies? This war was forced on us by the repeated abuses of a distant King, his Parliament, and monopolized trading companies.

A people should have a say in their government and what taxes are levied against them. Yet when we raised protest, we were met by British regulars in our streets and in our homes. Our “Olive Branch” petition wasn’t even read. Instead our ambassador in London was publically humiliated and driven from England under threat of arrest.

Hessian mercenaries were next, followed by blockades of our biggest harbours. Only those ships owned by companies affiliated with the Crown were allowed passage. We had to buy THEIR goods, pay taxes on them, and be grateful? The pennies of tax are one thing, but when the Crown makes it impossible to do business ...

This wasn’t a war we wanted, not at first. Those British soldiers who gunned down our citizens in the streets of Boston were defended by an American lawyer and fervent patriot, John Adams, and they were acquitted. We were mostly Englishmen by descent, we shared the same God and language. But the time for that has passed, I’m afraid.

The First Bloody Day

A Patriot Perspective

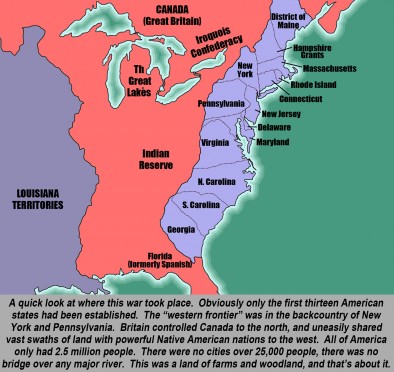

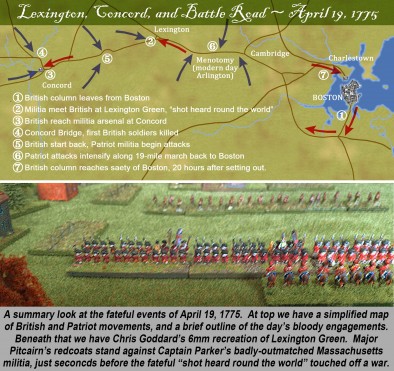

The American Revolution is generally recognized to have started on April 19, 1775. On this day, three separate engagements were fought along the roads west of Boston, Massachusetts. These were Lexington, Concord Bridge, and Battle Road (sometimes called the Battle of Menotomy).

The night before, General Thomas Gage (military governor of Boston), had secretly dispatched 700 British grenadiers and light infantry by boat from the port of Boston. Under the command of Lt. Colonel Francis Smith, their mission was to march on nearby Concord, where local militiamen had been massing arms and gunpowder.

This was an exercise the British had carried out many times before, and by now the locals were tired of such incursions. They also had plenty of warning about this “secret sortie,” leading to Paul Revere’s famous midnight alarm ride. Alerted by Revere and others, a force of militia soon gathered at Lexington Green to meet the British.

But the British would be marching all night, so the militia went home or adjourned to nearby Buckman’s Tavern. Shortly after first light, however, the British advance guard arrived at Lexington, commanded by Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines. Their ranks thinned by fatigue, boredom, and drink, the militia mustered out to face them.

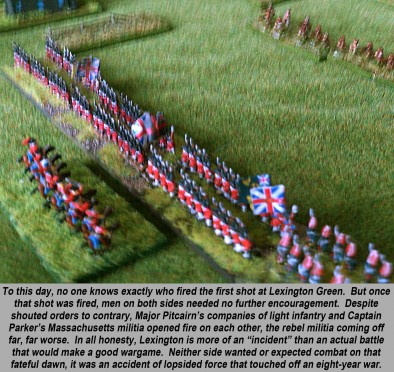

The standoff was far from epic. About 70 ragged militia (under the command of Captain John Parker) faced Pitcairn’s highly-trained light infantry. One side was bleary and bad-tempered after marching all night. The other was terrified, outnumbered, and probably hung over. Both commanders ordered that no one fire.

But someone did. To this day, no one knows who. This was the “Shot Heard Round the World.” The officers lost control and the two sides opened full fire. Eight militiamen were killed, the rest swiftly routed off. One British soldier was slightly wounded. The first shots have been fired, the first blood had been drawn.

For The Crown

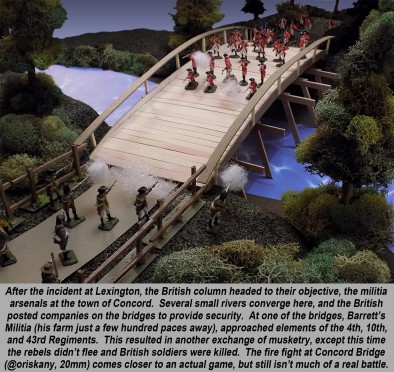

With the rebels suitably driven off, the King’s troops then continued on with their mission. They soon reached the town of Concord, found the rebel supplies, including buried cannon. Nearby rebels, having fled from the town before Pitcairn’s arrival, now saw smoke rising from Concord and thought the British had put the town to the torch.

The rebels swiftly advanced back toward the town from several directions, including the North Bridge over the Concord River. Several British companies, about 100 men, held the bridge, and again there was a tense standoff. Again, fire was exchanged. But this time, British soldiers were killed. An irrevocable line had finally been crossed.

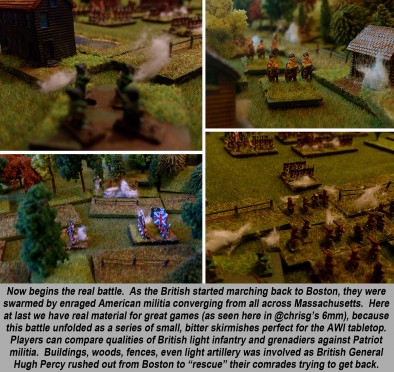

Yet the long and bloody day had only just begun. The British now had to march 19 miles back to Boston, and the gunfire at Lexington and Concord had alerted enemy militias all across the countryside. From all directions they converged on what became known as “Battle Road,” and started the Revolution’s first real battle.

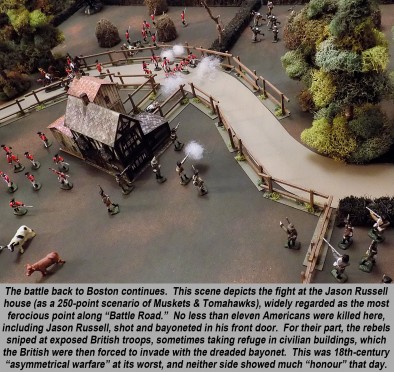

Battle Road, or the Battle of Menotomy (present-day Arlington, Massachusetts), quickly set the tone for just how bitter, brutal, and bloody this “glorious” American Revolution would be. Rebel militiamen poured out of surrounding woods and farms, firing from behind trees, fences and walls at British soldiers in the road.

Initially finding themselves in quite a bit of trouble, Pitcairn’s advance guard was soon reinforced by the rest of the British force and together they fought their way back to Boston. Along the way, parties or grenadiers and light infantry were dispatched to outflank “patriot” rebels, kicking in doors to get at snipers in windows, attics, and barns.

The fighting went town by town, field by field, house to house, and sometimes even room to room. Rebel losses were grievous, but so were British losses. They assailed us with their dreaded “widow maker” rifles, we gave them our dreaded “cold steel” bayonet. Finally, as the column got back to Boston, it was over.

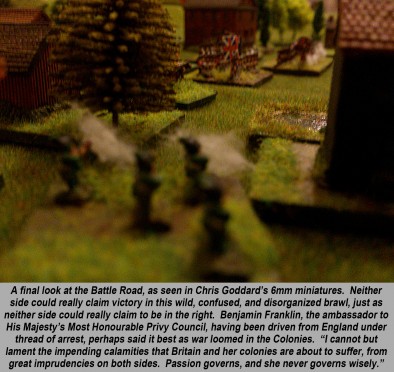

For better or worse, and regardless of the causes, the war was on. It wouldn’t end for eight long years. Even the Declaration of Independence, which officially announced the new “united American States” was over a year away.

Like those British regulars at Concord, we have a long march ahead of us. In the weeks to come, we’ll be rolling out more articles on the American Revolution, starting with Bunker Hill and wargaming our way all the way to Yorktown. What do you think so far? Please let us know with comments or questions below.

By James Johnson & Chris Goddard

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"...we’ll pull no punches when it comes to drumming up a little friendly “transatlantic Beasts of War” rivalry. We’ll just make sure both views are represented."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"...both commanders ordered that no one fire, but someone did. To this day, no one knows who. This was the “Shot Heard Round the World”"

Supported by (Turn Off)

![How To Paint Moonstone’s Nanny | Goblin King Games [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/12/3CU-Gobin-King-Games-Moonstone-Shades-Nanny-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

Thumbs up gents, great work! Looking forward to the next part 😎

Thanks, @suetoniuspaullinus . In the next part, things get pretty serious. Now that we’ve gotten through the introductions, causes, and the first skirmishes . . . Part 2 gets into some large-scale battles, starting with Bunker Hill (Breed’s Hill). 😀

Good first intro into the AWI, it’s always been a period I’m interested in and so looking forward to the next instalment.

Thanks very much, @chaingun . Stay tuned, it gets bumpy from here. 😀

Looking forward to the next one, remind me that I have the John Adams Miniseries on BlueRay but got distracted halfway through it …

Definitely an awesome miniseries, I have it as well. The parts pertaining to the American War of Independence are really 1-3, I think, after that it’s John Adams’ diplomacy overseas (he was our first ambassador to Great Britain after the war, that must have been a stressful job), his term as Vice-President, then President, then retirement (rivalry and reconciliation with Thomas Jefferson), and later life. Definitely a great show.

And from what I understand more correct than some movies. .. like the one with Mel Gibson

Oh dear God . . . yes . . . THAT one . . . 🙁

So I’m guessing Standartenfuhrer Banastre Tarleton will not be making an appearance in this series then? 😀

@silverstars – Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton will, yes. Colonel William Tavington (played by Jason Isaacs) will certainly not. 😀 Tarleton? Tavington? Really, Hollywood? Real slick, real subtle. That’s the limit of your creative friggin’ subterfuge? Make no mistake, Tarleton was a hard-as-a-coffin-nail merciless battlefield commander. But I’ve honestly never run across any actual account of his involvement in atrocities against civilians. And there certainly were horrendous atrocities in the southern part of the war, but almost exclusively by American Loyalists vs, American Patriots, and definitely vice-versa. I’m not 100% on this, but I think I heard that the screenwriters actually… Read more »

Great stuff guys! Being born and living all my life in New England I’ve been around all these places that parts of the war took place. It would be pretty cool to set them up on the tabletop. Actually I now live were one of the last British victories took place, Benedict Arnolds raid on New London. Even Today on its anniversary they shut Bank street down while a parade of citizens and re-enactors most dressed like colonials march down the street with a hanging effigy of Benedict Arnold firing off a small naval cannon. Its pretty cool. Can’t wait… Read more »

Awesome, @barretem30 , and thanks! Yeah, Benedict Arnold basically burned down New London before he was sent south to Virginia in the last months of the war. I’m actually pretty “soft” on Arnold, looking at the first three years of the war and everything he did to keep the war going for the patriot side. I guess this is part of what made his eventual betrayal and treason such a blow for the Americans. As Washington himself yelled when it happened: “Arnold has betrayed us! Who can we trust now.” I think the New London incident is even more telling… Read more »

This is great, so many places and conflicts I had heard about, but good to put things into order and flesh it out. Looking forward to the next article.

Thanks very much, @sheepman . Indeed, a lot of these names, places, and dates are just kinda jumbled up in a general vague awareness – Bunker Hill, Saratoga, Valley Forge, Yorktown . . . Washington, Cornwallis, Howe . . . wasn’t Mel Gibson in this war somewhere? 😀 In the course of this series I hope to at least sketch out the general time line. The main focus remains on gaming, of course.

great job gentlemen 🙂 PDF versions would be greatly appreciated, stop my boss from catching me online 😉 😉 😉

I know the feeling, @buggeroff . . . 🙂 I’m typing this in a discrete corner of my screen right now. 😀

hahahaah, excellent. shhhhhh going to hit minimise 😉

hope all with you and the family 🙂

Looking forward to the rest of the series, as its a topic im mostly completely ignorant on, well not for much longer :D, keep up the good work @oriskany & @chrisg

Thanks very much, @nakchak . Again, we’re covering eight years of conflict in just five articles, so we can’t get into a lot of detail, but we hope to just get people familiar enough to run some games if they’re interested. 😀

I know very little on this topic, but am really looking forward to following this series. Cheers, Fellas! Keep up the great work!

Thanks very much, @niktyrrell . 🙂 We’ll be rolling out new articles every Monday for the next four weeks.

Excellent first article to a period of history I know so little about, so I will treat this series as part of my education. Historical gaming is something that I’m increasingly being drawn into (as is real ale – is this an age thing?) more for the learning aspect. One interesting point is the comment on perspective. I can understand Americans having a greater attachment and patriot view of the war given that it created your country. However, and perhaps this is just me, but as a Brit, it raises no ill feeling. After all, if I had to harbour… Read more »

Regarding our perspective, it’s just that I think the two biggest “demographics” in the BoW community are the UK and the US. In so much historical gaming, these two nations are naturally allies (WW2, Team Yankee, moderns, etc). Here was one war where the “two sides” of the BoW community were squarely set against each other. Now granted, the conflict is 240 years behind us. But I’ve encountered lots of historically-minded gamers from the UK (and I totally agree with them) that the way this war is often remembered in the US is kind of a joke. British “lobsterbacks” are… Read more »

I am sooooo looking forward to getting all the kids to bed tonight to sit down and read this … Hopefully with a good glass of JD 🙂

Hey, we are visited by the man himself! Thanks, @warzan. We hope you like the article when you get a chance to read it. You know, we could do a follow-up series on the War of 1812, complete with the battle of New Orleans. But we’d have buy some “alligator artillery” miniatures to complete the tables. 😀

We fire our guns, the British keep a comin 😉

That line is from the Battle of New Orleans, the second US/UK war. Better known as the war of 1812. Of course the Battle of New Orleans was fought in 1815, after the peace treaty was signed.

All right, @blipvertus and @warzan – I wasn’t going to do this . . . but here it is.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VL7XS_8qgXM&list=RDVL7XS_8qgXM

Music starts around 00:28

Living next to Bushmills and drinking JD?! Ok, looking at the subject we will let that one slide 😉

That’s American whiskey you’ll be drinkin’ sir! American whiskey!

Hello all and thanks for the great comments from both Chris G and myself. I really like the idea that we have been trying to get started of support for both sides yes, but pick a side and let the di of fate roll the numbers. I love the way the Patriots scream we do not want to fight, can’t we talk about it etc and then attack our loyal troops so far from their homes and loved ones posted in Boston. They were trying to stone a lone guard to death. The troops that responded did so out of… Read more »

Thanks for checking in, @victoriag and @chrisg ! I guess it goes without saying, but I’ll say it again anyway. These articles are totally a team effort between myself and @chrisg – wouldn’t have been able to do them without his help. 😀 Okay, now that the polite part of the message is over . . . 😀 (putting on the tricorn hat to play the firebrand hot-head rebel for a moment) . . . . . . and please remember I’m just playing around here . . . Regarding the sentry at Boston – What can I say? Boston… Read more »

ah, Paul Revere what a numpty – my six-times great Grandfather was a young British officer that got himself caught up on the receiving end of the Penobscot Expedition where the garrison gave the army of Massachusetts a bloody nose. Think it’s also worth pointing out that the conflict in the America’s began a full two years before hostilities broke out in Europe – between the aggressive behaviour of the settlers of Georgia and the incompetent handling of negotiations with the French courtesy of a land pirate like young Mr Washington I do believe my colonial cousin that our American… Read more »

Good points, @bigdave, although I admit I only have a conversational knowledge of the French and Indian War / Seven Years War. @elessar2590 is the real expert on this, I think he had a whole part of his article series specifically about how the war started (Washington, Half-King, Jumonville, etc.). I have to raise an eyebrow, however, on the idea that George Washington “started” the FIW and by extension, the Seven Years War. That was a war that was waiting to happen, and the crown made a fortune off that conflict in possessions taken from the French. I’m not sufficiently… Read more »

Started is probably a bit strong of me tbh, but it certainly contributed. British administration of the colonies could be terrible at times, Washington being merely part of it at the time. Local aggression combined with inadequate handling from further up the chain the America’s were always going to be a powder keg. To be honest, far from Maine being the key point of contention in that region it was Louisbourg and the surrounding environs. It was an important and strategic way station that allowed for the resupply of passing fleets, with the resources being drawn from Nova Scotia and… Read more »

This is great, @bigdave – I actually didn’t know very much about the Penobscot Expedition, Louisbourg, or Nova Scotia’s part in the Revolution. I mean, I knew it was Howe’s big base when he withdrew from Boston – March 17, 1776, and re-launched a new campaign into New York and Long Island in August later that year. Right, I don’t know if the Americans ever thought Maine was somehow “important,” but at least twice they tried to use it as some kind of invasion route to get to important areas in Canada. Both times ended in disaster. I know a… Read more »

I recommend Bernard Cornwell’s book ‘The Fort’ a ripping yarn about the Penobscot Expedition.

Thanks, @ozzie . Others have made the same recommendation, so I will definitely have to check out that book. 🙂

woo hoo!

🙂

If only the Rebels had crossed the Atlantic and finished the job… (Not realistic for a multitude of reasons I know. Would have been interesting, ehy!)

*ahem!*

Super fascinating area of British history, and in my own experience I have to say, the period is not spoken about in the UK let alone covered in the education system (things might have changed now).

Cool article!

Thanks, @dice ! “If only the Rebels had crossed the Atlantic and finished the job…” Well, not for lack of trying. In April 1778, John Paul Jones and his ship USS Ranger did try to bombard and raid the town of Whitehaven (Cumbria, Northwest England). Managed to spike some guns and set a few fires but that’s about it. A similar raid was mounted on St. Mary’s Isle, but again with less than total success. More significantly, as soon as France entered the war, a crisis developed in the English Channel that soon led to a pretty serious naval battle… Read more »

Whitehaven was a farce! Used to live in Lancaster (just round the coast), the crew of the Ranger tried to set fire to some coal barges in the pouring rain (trust me, it rains a LOT in that corner of the country), soon gave up and like any sensible bunch of sailors abroad they went to the nearest bar. That’s not to say it didn’t terrify the government – considering that for every £1 the American colonist was paying in tax to the crown, your average Briton back home was paying £17 (I think, been a while since my uni… Read more »

Okay, okay, @bigdave . 🙂 Whitehaven was hardly the Battle of Hastings, and John Paul Jones was no William the Conqueror. I always thought it was mostly a publicity stunt to get Jones’ name mentioned in Congress, and a bigger ship so he could take bigger prizes. Not really my specific area of expertise, though. These kinds of privateers, though, did threaten to get out of hand by war’s end. One of Washington’s best units, Colonel John Glover’s “Marbleheaders” from Marblehead Massachusetts vanished from the order of battle almost to a man so they could sign aboard privateer ships and… Read more »

Great stuff … ten times more exciting than boring old history classes.

Although to be honest the American and British wars weren’t much of a topic for us as we had our own wars to be reminded of.

And once more we’ve got proof that wars never are as neat and tidy as they often appear in summaries.

In keeping with the theme one may also consider Sid Meiers’ Colonization as background material : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sid_Meier's_Colonization

There’s even a free open source variant : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FreeCol

The original DOS version of Colonization did get me interested in the period first time around – not being from any of the 2 sides it where not touched in my history classes

Thanks, @limburger – although if I’m looking at your BoW profile right . . . 😀 The Netherlands were eventually waist-deep in this war, as well. As I’m sure you know, they were the economic power-house of the day, they helped us establish national credit and made loans to us during this period. They also supplied us with arms covertly through a smuggling operation based out of the island of St. Eustasius in the Caribbean. Finally the British had to declare war on the Netherlands to shut it down (November 1780, I think). Dutch spies were also instrumental to Washington… Read more »

It’s the one aspect that isn’t given much attention in history classes in my time.

I think the last bit of old history we had was about the 80 year war against the Spanish (basically our ‘war of independence’ … :))

Then we had our ‘golden era’, which was glossed over and it was straight into WW2 as the last bit of history I remember from school.

It might have something to do with how much profit we made from slave trade in addtion to the spice trade (by the VOC)

Oof, the Eighty Years’ War ( 1568–1648). There’s a long subject. I don’t think we could cover that in five articles. 😀

lol … It’d be a challenge just to cover the highlights.

I’d love to see someone try though.

Sounds like you just signed yourself up for a project, sir!

– just kidding – 😀

It would be a quick read, though.

“PART ONE – The First Twenty Years . . .”

I know so little about this, great and well appreciated effort.

Are there any books you recommend on the subject!

@bigbadbazz ~ One that I definitely like, especially if you’re looking for the “you are there” feel of the war, is Joseph Plumb Martin’s A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier: Some Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings of a Continental Soldier. This was an autobiography actually written by a Continental soldier, the only book of its kind. Started as a private in 1776 (Battle of Long Island), wound up alongside Alexander Hamilton in the nighttime bayonet charge against Redoubt #10 at Yorktown (sergeant in the engineers, 1781). http://www.amazon.com/Narrative-Revolutionary-Soldier-Adventures-Sufferings/dp/0451531582 Another good one is Patriot Battles by Michael Stephenson. Despite the title, it presents… Read more »

A buddy and I are just starting to get into the AWI. I wanted to play napoleonics, he something more asymmetrical. I wanted to play 10mm, he 28mm. So we landed at the AWI in 20mm. Already tried muskets and tomahawks and the system seems quite interesting, but not for the larger engagements. Anybody tried british grenadier at some point? The article series comes at a perfect moment for us. Normally you don’t get anything about the AWI in history classes here in Germany. Nearly anything a lot of people know about the conflict is from “The Patriot”. And we… Read more »

Which figure range dd you end up going for?

@bothi – Well, if your friend wanted something asymmetrical, the AWI is definitely a good choice. That said, by the end of the war the American Continental Army has evolved to the point where the warfare becomes much more conventional for the period, so the AWI really gives you a lot of choice. What I find appealing about it from a gaming perspective is the relatively small size of the engagements. You can do a battle that “really matters” with a much smaller figure count than you can with Napoleonics (although I guess there are exceptions, like the Peninsula Campaign).… Read more »

If muskets and tomahawks doesn’t quite fit maybe try the Eagle Rampant rules (variant of Lion Rampant for Napoleonics). I only got them this weekend so not had a chance to try them yet. They are printed in the latest Wargames Illustrated issue.

http://wargamesillustrated.net/medieval-napoleonics/

I think I would wait for Sharpe Practice 2 by Too fat Lardies

@koraski and @torros – thanks for the comments and tips! I looked at Muskets & Tomahawks (which is great, don’t get me wrong I’m not trying to give it a bad rap here), Rebels & Redcoats (too large in echelon level) and Redcoats & Rebels (yes, a different game, amazingly detailed but honestly too complex). Also, Redcoats & Rebels was a “command tactical” game where each figure represented about 50 men. I haven’t heard of these two games you guys mention (“Eagle Rampart” and “Sharpe Practice”). I’ll have to check them out. Muskets & Tomahawks worked great, in fact we… Read more »

I had a look at the 1st edition of Sharpe Practice and a Terrible Sharpe Sword the ACW version/expansion. Great rules on paper at least the project never got off the ground and on to the table

@torros We actually haven’t bought anything yet, but thinking about to get the main body of armies in the close to 20mm plastic ranges like airfix (just because they are cheap like hell). To fill the gaps we probably going for BandB Minitaures, which should be a close match to the airfix ones. What would you recommend? @koraski and @oriskany As mentioned above we tried Muskets & Tomahawks and liked it a lot. I guess it will be part of we will be doing. It seems to fit really well for the small engagements. But we are looking for a… Read more »

Indeed, @bothi , there were quite a few flavors of British, or more accurately, “Crown” forces. The basic British line regiment was just under 600 men, divided into ten companies with a theoretical strength of 56 men. Actually, the real strength was 53, with the pay for these missing 3 men pooled into a “company fund” to help defray costs for uniforms, equipment, boots, etc. Of those ten companies, eight were classic “line infantry” (the prototypical “redcoat”), one was a grenadier company, one was a light infantry company. Many generals would detach all the grenadier and/of light infantry companies from… Read more »

An interesting read for anyone interested in the period is The Fort by Bernard Cornwell of Sharpe fame

Yeah its a fun read

Personal favourite 🙂 Moore got my six–times great grandma up the duff so I’m a descendent of his

Sir John Moore, @bigdave ? Damn, that’s pretty awesome. I don’t have any relations from the war, both sides of my family I think were still in Europe (Mother’s side – Irish Catholic, Father’s side, Scot).

The Penobscot Expedition – this is where Paul Revere gets courts-martialed right? Yeah, like I said above, I don’t really understand why he’s included in the “pantheon” of American heroes of this war – especially when other like Nathaniel Greene get overlooked (okay, Greene was something of a profiteer, but this was accepted practice at the time for officers of all armies).

yeah – was a nice chap, was well respected as an MP but didn’t stop him having a wilder side when he was younger then buggering off to the army haha. Revere ended up out of his depth, decent sized force of regulars in a fort (even if it was a hastily built pile of logs) is a daunting prospect for anyone, let alone a force comprising mostly of militia. The sharpshooters did well for themselves as I understand, they did strongly influence the light infantry doctrine installed into the army later on by Moore at Shorncliffe. If it wasn’t… Read more »

I think part of Paul Revere’s overly-precipitous rise in the Patriot ranks was due to his chance helping of fame from April 18, 1775 . . . and his personal connection to early Sons of Liberty figures like John Hancock and Samuel Adams (these were the two guys he met in Lexington that fateful night. Hancock was one of the richest men in America, plenty of money to throw around (or help raise “personal” regiments and contribute “privateer” ships to a prospective fleet). And of course Sam Adams was the “mouth” of the early Revolution, instigator of much of the… Read more »

I would have to agree with @limburger – if only history classes had been as good as this.

Well written and very absorbing. Nice job. That bridge looks awesome!

Another triumph. Jamie is wanting to know about the hex-game you are using.

@unclejimmy I think @oriskany gave an overview of the hex game some weeks ago on the Weekender thread

Thanks @unclejimmy and @rasmus – Indeed, this was the “Tactical Sons of Liberty” (working title only) we had on the UncleJimmy Thread one time, where Rasmus Petersen’s Pennsylvania riflemen were among the forces under the command Brigadier General Johnson’s army, which met the redcoats of Brigadier General Goddard (which included the dragoons of Captain D. Oliver) at the epic Battle of Pauls Manor.

Alternate history at it’s best, baby!

Unless of course, Jamie’s talking about the larger-scale 1776 Avalon Hill game, with the whole Thirteen Colonies laid out in a game that covers the whole war (if you want).

Which were also previewed 😉

We were doing pretty well in that battle, @rasmus , until one of @cpauls1 ‘s Canadian militia shot me off of my horse. 🙁 We’ll get them next time, once my shoulder heals. 😀

That’s right, we also ran through a battle report of the 1776 campaign. I have to run that again, the British totally ended the war victoriously in December 1776 in that game. Now that I know the rules a little better it’s time for some payback. 😀

Another great article, another historical period I need to start in on. Why do you do this to us??? I still haven’t finished the afrika Corp and Desert Rats forces! What’s next? Boxer rebellion? Punic Wars? I’m sure it will be something I didn’t know I wanted to collect…

Boxer Rebellion? You know. @koraski , that’s not a bad idea. The Anglo-Zanzibar War, the “100-hour Soccer War” between El Salvador and Honduras in 1969 . . . I’ll leave the Punic Wars to @redben . 😀

Glad you liked the article. As far as collecting and building too many armies, well . . . that’s what hexes and counters are for. 😀

Excellent stuff, i look forward to the rest of the series.

Awesome, thanks very much, @hairybrains ! Great userID, by the way. 😀

Great read @oriskany and @chrisg !!!

I have learned so many new things today. Yep, my knowledge of the war was more like you poined out… red vs blue. I need to read more about it thou. I am waiting impatiently for next instalments! The two perspectives narrative is great and gives a lot of insight.

btw. any introductory books on the topic?

Thanks very much, @yavasa ! Yep, we’ll be running another article each Monday for the next month or so. Glad you’re liking it so far.

A good book to start with is Patriot Battles by Michael Stephenson. Despite the title, it presents a very balanced look at how these two sides were put together on the battlefield, how a British regiment was actually assembled, how much they were paid, how both sides were armed, how each battle played out and WHY it played out that way. Very important from a wargaming perspective, at least for scenario design.

http://www.amazon.com/Patriot-Battles-How-Independence-Fought/dp/0060732628

Thank you sir!

No worries, @yavasa . It also presents rather stark portraits of a lot of the military leaders, both merits and flaws. Just as an example, Washington’s issues with gender and race, and his rather appalling lack of tactical finesse, are balanced against his operation genius and amazing leadership abilities. I don’t think the writer is trying to “tear anyone down,” but present a more honest view that frankly makes me appreciate the good qualities all the more.

Found Turn on Netflix should see me though the week

It’s not too bad, mostly espionage and soap-opera drama, instead of too much battle and combat. Again, I’ve only seen the first season, though.

That is all Netflix have as well … But on “holiday” at the in-wars so need something 😉

All week with the In-Wars? Uh oh. SOunds like you might be starting a Revolution of your own, @rasmus . 😀

Monday nights are going to be full from now on as it is my club night too. Great start to the series with setting the scene, this conflict is not one of my strong points so I’m looking forward to getting some inspiration to exploring it more.

I feel sorry for community members who have posted that they wished their history lessons were as interesting at school. For me History was the only redeeming feature of school. I was fortunate enough to have a really good history teacher though.

Can’t argue with that, @huscarle (history being the best subject at school). Glad you’re liking the series so far, there’s a lot more action to come as we start getting into the battles proper in Part 2.

Good overview and enjoyable read. The long 18th Century has long been a favorite period of history for me from both an English history perspective (esp. most things relating to the growth of progressivism in arts, sciences, and politics through the Enlightment as experienced in England) as well as from the American Colonial point of view – especially how many of those Enlightenment ideals evinced themselves in the expression of self-governance in the Colonies. The discussion of taxation without representation was good, but I was hoping some of the other Acts passed by Parliament during this time in relation to… Read more »

Points well taken, @rangerruss – there would indeed be plenty more to put in there. The Stamp Act, the Intolerable Acts (Boston Port Closure, Massachusetts Governance Act, Justice Act, Quartering Act), etc. I just didn’t want us to get bogged down in the politics, and wanted to move us to the wargaming as quickly as possible. I think that’s what people on the site are most interested in reading about. That said, I thought at least a little “background color” from both sides’ perspective would help establish why the “little plastic men” on our tables were shooting at each other.… Read more »

@bothi. The soft plastic figures are cheap but you’ll struggle to get all the different troop types you need. As I mentioned earlier there are some nice 20mm metals from irregular they sometimes get a less than favourable press but the range from what I can see is complete and they usually paint up better than they look on the website

I guess I should say the ones I got were these, many years ago, long before I ever got into miniature wargaming (I got them as literally just “plastic toy soldiers”)

Not bad detail, at least on the Americans. The British not so much, and they’re also a little smaller than the American counterparts. Again, not strictly “miniatures” – as opposed to “plastic army men.”

http://www.classictoysoldiers.com/cgi-bin/ctsc6/rtl/phd.cgi?Autoincrement=003700&tag_rf=25mm%20Toy%20Soldiers+Rev%20War%20(25mm)%20Manufacturers%2025mm+IMEX

Is the size and details a PR ploy ? To make the crown look bad 😉

Ha, @rasmus . . . But I think just inexpensive, inconsistent minis. 🙂 When you get 200 pcs for $35, well… This is what happens. I know you’re kidding around, but it occurs to me that I’ve been talking about Muskets & Tomahawks and people might think these minis are FROM M&T. They’re not, I just used part of the game system

Can’t say enough about this gents. Well done @oriskany and @chrisg … a brilliant collaboration! 🙂 I’ll save my questions for the end, as I know there’s four more instalments. Again, congrats to both of you 🙂

Thanks very much, @cpauls1 . Glad you like it so far! 😀