“The Other World War 2”: Wargaming in the Pacific (Part Three)

August 18, 2014 by crew

Welcome to the Jungle

In our previous two articles on Wargaming in the Pacific, we’ve looked over some of the key arenas of the Pacific War, and briefly discussed their different characteristics and how they pertain to wargaming. So let’s get “stuck in,” as they say, with some actual examples of what a Pacific wargame might look like.

In this article, we’re “headed to the jungle,” walking through a potential Pacific campaign step-by-step, with what I hope are helpful ideas, suggestions, and examples along the way. Since our first article was about the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theatre and the South Pacific, let’s start with a theoretical campaign that shares characteristics with these arenas – large landmasses, dense jungle, long campaigns, and rugged mountains. My hope is that players interested in recreating the exploits of the Chindits, Gurkhas, Merrill’s Marauders, or the Australians of the Kokoda Track will find this material helpful. A similar exploration of the Central Pacific and naval operations will be outlined in our next article.

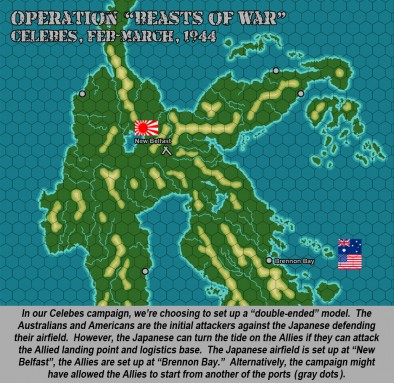

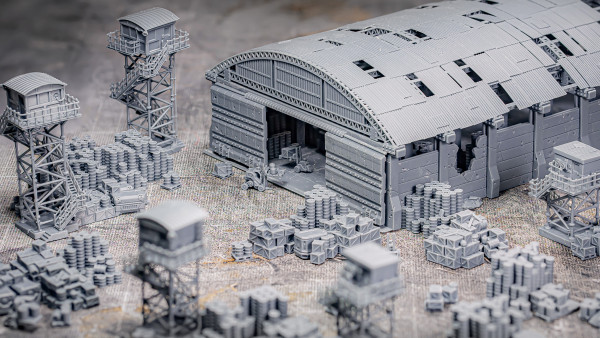

Naturally, the first step in setting up an effective jungle campaign is to pick a location. To free ourselves of as much “historical baggage” as possible, I’ve selected a jungle campaign that never happened, an Australian-American invasion of the island of Celebes. This frees us to set up whatever kind of forces we want and delve strictly into gaming. For our campaign, we’re saying that the Japanese have built a large airfield in the northern highlands of Celebes, one which has to be taken to support the bigger Allied drive on the Philippines. The airfield is inaccessible from the north or west, so the Allies must land an invasion force to the southeast and embark on an epic jungle trek to knock out this vital airfield.

In setting up your campaign, it’s important to decide who is on the attack and defence. In some cases, such as a Chindit raid or a Merrill’s Marauder operation, the Allies are on the attack the whole time. The Japanese player wins simply by stopping them. In contrast, the Japanese started out as the attackers along the Kokoda track, but were eventually put on the defensive by counterattacking Australians. To a certain extent these campaigns are epic wilderness treks with a little combat thrown in, and you need definite “anchor points” at either one or both ends. In a “double ended” model (such as Kokoda Track), not only does the initial defender have to stop the attacker, but then carry over the offensive and take the initial attacker’s base.

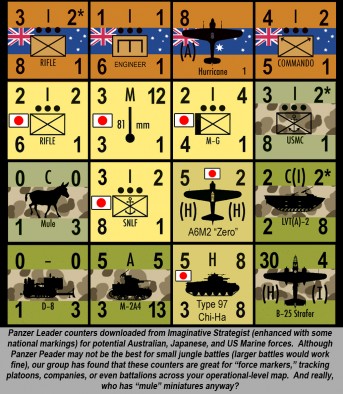

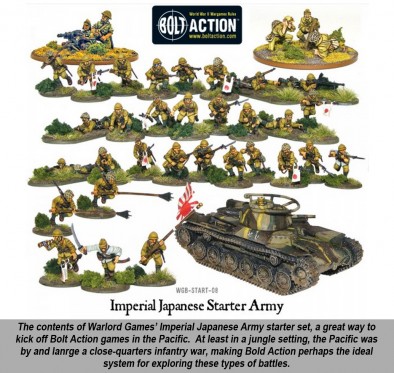

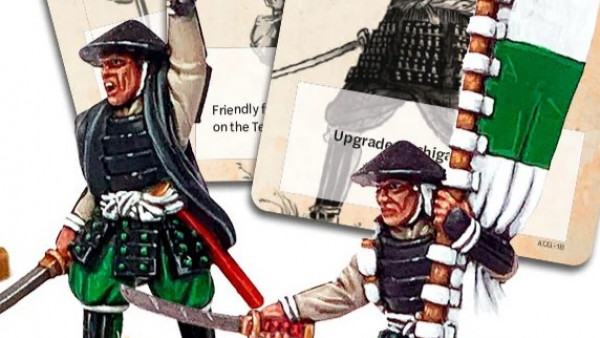

So our Australian and Americans have each landed a regiment of about 1600 men (eight companies each), set up a base of operations, and begun their trek toward the airfield. By this point you should have chosen what gaming model you’re using, either for tactical or operational-level gaming, or both. One familiar choice for tactical battles might be Bolt Action. Warlord has all kinds of great infantry miniatures available, and the game is flexible enough to support Pacific infantry battles as well as European. Flames of War might be a tougher sell, since tanks and heavy equipment are such big draws for that game and honestly, the trackless jungle isn’t the best place for tanks. Valor and Victory is another great tactical choice if you just want to experiment with the Pacific without up-front investments for miniatures. Our group has experimented in the Pacific with modified versions of Avalon Hill’s Panzer Leader . . . with mixed results. However, Panzer Leader counters would make great force markers for your operational map. The Kokoda Track campaign started out with just 1000 men or so, which equates to just 20 Panzer Leader counters. A huge variety of counters is available for download at Imaginative-Strategist.com, and they’d provide a quick, easy, and inexpensive way to track operational movements, allowing you to focus on the tactical action.

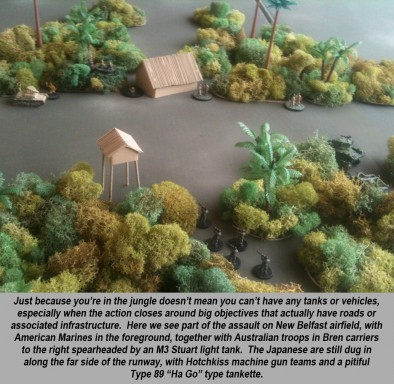

This isn’t to say that armour and vehicles have no place in a jungle setting. The legendary British General William Slim found tanks to be surprisingly useful in certain defensive aspects of jungle warfare, covering the retreat of withering British and Chinese infantry divisions in Burma during the dark days of 1942. As would be seen later in Vietnam, tanks can play the role of “goal keepers,” locking down important roads, firebases, airfields, and ports. If an enemy infantry force has just slogged for weeks through mountains and jungles, equipped only with weapons they carried on their backs, the last thing they want to see at the end of their trek are your tanks defending their objective.

Other vehicles should not be underestimated, all the way down to the lowly bicycle. The Japanese General Yamashita famously moved 70,000 men with lightning speed down the Malaysian Peninsula through the use of 20,000 bicycles. This seems impossible, given that there weren’t even enough bicycles for all the men to ride. But they slung their 40-kg packs on the bikes and walked them down the jungle trail, thus multiplying their marching power while the British had to carry their packs in the suffocating jungle heat. Conquering half of Southeast Asia with bicycles may seem funny, but the 92,000 British forced to surrender with the Fall of Singapore found nothing humorous in Yamashita’s “bicycle blitzkrieg.” The Americans of Merrill’s Marauders, meanwhile, were famous for their use of lowly mules, hardy enough to carry hundreds of kilos through even the steepest of Burma’s jungle mountains. Still not sold? Remember that bikes and mules don’t run on gas, and remember how difficult supply in the jungle can be.

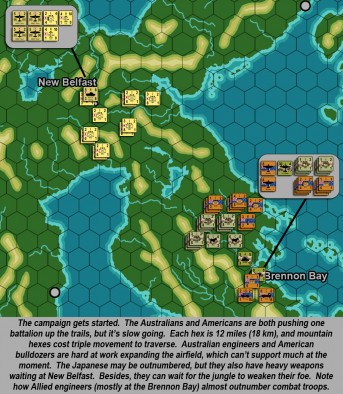

So our Australian and American regiments each send one battalion (600 men, or three companies) up the jungle trail, with the rest of the men establishing a defensive perimeter around their base and starting the construction of their airfield. In our example game, we’re saying that each company of men that stays in the base can supply one company of men in the jungle. This way thousands of Americans and Australians can’t just pour out of their ships and stomp off into the rainforest. However, the Allies have kept even more of their companies back at the base. Part of this is for security, but they’re also using these surplus supply points to begin the construction of an airfield which will yield and extra ten supply points per turn if they can get it built. Building mechanics like this into your game encourages resource management, logistical planning, and rear area security.

The game might also allow for operational-level counters to be played on the map inverted, so the opponent doesn’t know what exactly is in each force. Aerial reconnaissance, patrols, or even friendly locals might pick up an enemy column in the jungle, but knowing exactly what each enemy force has is probably impossible until the forces collide and the shooting starts.

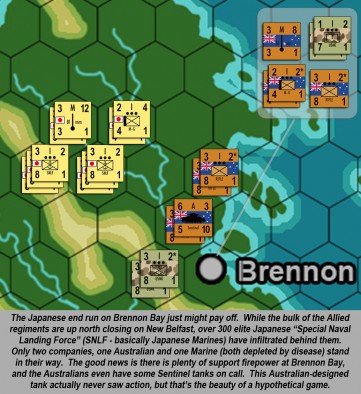

So at the end of each operational turn, opposing counters that are in contact with each other are flipped up and revealed, and miniatures games are run to resolve the action. In each tactical game, available forces are based on the strength of the operational-level counters in question. But wait . . . perhaps the Japanese player has set up a screen of multiple weak companies to dupe the Allies into attacking straight up the trail, only when the counters are flipped up does the Allied player see there are only sacrificial platoons. Meanwhile, a single powerful counter (perhaps a whole battalion) is swinging around the side, hoping to avoid battle completely and make a run for the Allied base. Maybe the Allies use some of their air assets to try and attack or locate this force, perhaps forcing the Japanese player to flip it up during a “reconnaissance phase.”

One phase you definitely should have in any jungle game, however, is a supply phase . . . and it needs to be tough. If either side is never really stretched to keep their men in food, clean water, and medical supplies, consider tightening up the system. Units that are not “in supply” shouldn't automatically vanish, but instead suffer a harsh penalty on some kind of “Disease Table” that tracks the unit’s effectiveness against malaria, dysentery, and malnutrition. Spend more than one turn out of supply or get a bad roll on that disease chart, and yes . . . units can simply vanish, “swallowed” by the jungle that is equal enemy to both sides.

Needless to say, this is only scratches the surface of what building an actual CBI or South Pacific jungle campaign would be like. I’m hoping people start posting below, because there are mountains more to say on the topic. Air supply drops, supporting amphibious landings, the Japanese Navy landing additional troops or using submarines to interfere with the Allied support fleet, the possibilities are endless. So “Welcome to the Jungle” as the song goes. Don’t get lost in here. We may never find you.

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"...the last thing they want to see at the end of their trek are your tanks defending their objective"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"“Welcome to the Jungle” as the song goes. Don’t get lost in here. We may never find you..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

A quick thanks to oriskany for the name of the bay ;)!

BoW Ben

Which bay is that? Oh, Brennon Bay? Eh . . . that’s a [ahem] complete coincidence. 🙂

Another excellent article, keep up the good work! Do you have any suggestions on jungle flora?

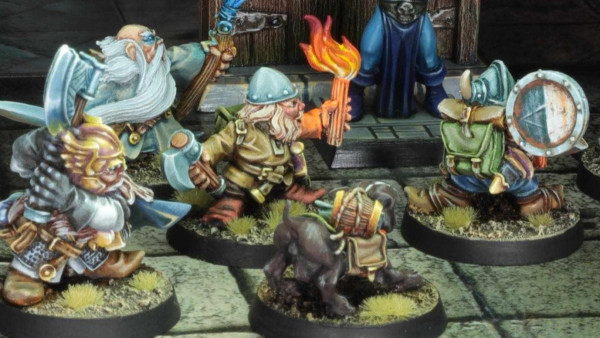

Thanks, @leoleez . For jungle foliage, because I tend to need so much of it to make a nice thick jungle, I go for the cheapest, fastest, and easiest thing possible. I go to the craft store and buy bags of multi-colored “preserved sheet moss” (usually about $5 USD a bag). Then I cut circular and oval-shaped pieces of thick cardboard and paint them LIBERALLY along the top in ordinary white wood glue (I use pretty thick cardboard so it doesn’t warp when I do this). I then stick different-colored fingerfuls of moss on the cardboard, squeezing it tightly together… Read more »

so you are concentrating on the under bushes of the jingle not the trees you could represent the trees with kitchen rolls painted in browns&greens?

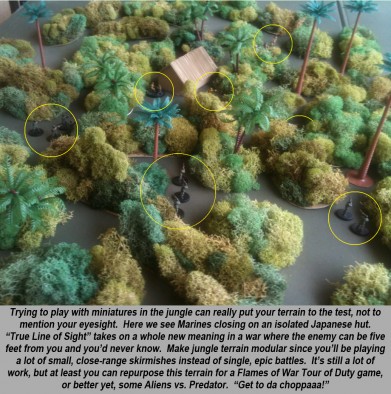

An actual “canopy” would be much more realistic, agreed — undergrowth bushes along the jungle floor, followed by **another** layer of foliage somehow suspended over the map on trunks of some kind. You could have little vines of string or yarn or something, it would look great. I suppose it’s possible, but when I set up the mini-boards depicted above and took the picture, I found that you could barely see the infantry figures anyway (hence the yellow circles). Also, players would have to reach down through the canopy to move the figures, and measuring ranges would be an especially… Read more »

Yup that’s why I was thinking if you use kitchen roll or bamboo cut at the nodules to represent the tree trunks you can work through the forest / jungle without having the Hassle of the branches getting in the road.

Gotcha. Thanks, @zorg !

A brilliant article certainly brings a new perspective to the jungle wars similar to Napoleonic era wars. Where large numbers of the army will be lost to various problems for large armies moving through countries using supply’s quicker than acquiring them.

Thanks, @zorg . From what I’ve read on these campaigns, supply was indeed the killer. But rather than let that limit the campaign, players can experiment with rules for air-dropped supply (as used in Burma by Chindits and Merrill’s Marauders), making simple jungle learings incredibly important objectives for campaigns. They’d also hack out runways from the jungle so light planes could actually land and they could evacuate the wounded. The Japanese were also good and bringing in supplies and reinforcements by sea (as seen in Guadalcanal’s “Tokyo Express”), adding another potential supply dimension to a jungle game.

Are their rules for foraging so units with no supplies will be forced to forage instead of advancing?

I’m not sure, @zorg . Personally, I would not include rules for foraging in a Pacific jungle game, simply based on historical precedent. These columns were always marching through incredibly thick (i.e., lush) jungle but starvation was still always a threat. The most jagged example I can think of is evidence along the Kokoda Trail. When this campaign turned against the Japanese and some of them were cut off, Australians would later find evidence of cannibalism, inflicted both on Australian POWs and Japanese wounded, so the rest of the force had a chance of survival. So as thick and as… Read more »

That’s true you could loose more men trying unknown food than just pushing on and taking out the enemy then getting supply’s from the airport / port you’ve just captured.

Now that DID happen, and quite a bit. For quite some time during their campaign on Guadalcanal, the 1st Marine Division subsisted on captured Japanese rice . . . after the Navy was largely unable to support or supply them after the American-Australian naval defeat at the Battle of Savo Island. So to tie back to some of the possible examples sketched out in the article, taking an enemy supply base, port, embarkation point, airfield, or some such . . . could yield like a one-time award of 10-20 supply points. This would keep 10-20 companies in the field for… Read more »

Plus they will have an extra supply point base to use.

Thanks, @zorg . Our last article part should hopefully come out tomorrow. But you’re right about the supply bases … Assuming the attackers could take and HOLD the base, as opposed to taking it and just raising all the supplies. 🙂

Great article once again. Thanks for doing these, they are really interesting.

Thanks very much, @ghostbear , for the kind feedback! 🙂

What can I say? Nothing to add since the article covers everything. Thanks @oriskany

The article covers everything? If only that were true, @yavasa . 🙂 But, short of a column of text 10,000 words long that would wear out everyone’s mouse wheels scrolling through it . . .

Thanks again for the support and positive feedback. 😀

The step by step is incredibly helpful, thanks! Hearing the basics of running a game is one thing, but actually hearing steps and challenge resolutions, give me at least, more confidence to try one of these myself.

I also appreciate the movie/mood tips. I find gaming can sometimes be more fun with a little inspiration playing in the background.

Thanks for another great article.

Good stuff. Where to begin? Having a cat named Belfast, I like the name of the Japanese port. 🙂

But seriously, nice job again showwing how operational set-ups can lead to tactical battle/games without any one facet getting too complicated.

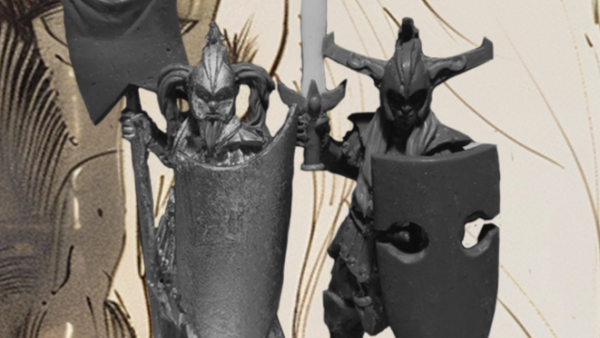

Your terrain and mini pics look outstanding. My favorite is the battle on the airfield. Heck yeah, that Stuart can be damn scary againts a HaGo and some infantry.

Keep ’em coming Oriskany. Great!!!!

Thanks, @amphibiousmonster . Well, there’s a New Ireland and New Britain in the South Pacific, so I couldn’t use those, but was trying to keep with that theme. 🙂 A Stuart would indeed be pretty scary on a battlefield where the next biggest thing is a knee mortar or that crap little Ha Go tank on the left. 🙂 Would tanks, even tanks this small, be in such a battle? I only assumed that an airfield would have to have a road leading to it for fuel, heavy weapons for air defense, barracks for ground crew, Roads are few and… Read more »

Thanks, @gladesrunner . Of course these were just examples of a step-by-step. A true step-by-step involves two things . . . one, a titanic article no one would want to read and two, my new job at a game design company. 😀

Great, really interesting article. All of the emphasis on supply – in the article and the comments – shows just how important it is to get the feel for the setting. Not just to replicate the threats the troops of both sides faced, but also the reason behind many of the scenarios you could fight. It would be easy to come at this with no knowledge of the setting and set up marines and Japanese fighting over a hill top, but by emphasising supply, you inspire games based on getting to supply points, defending them, capturing supplies, keeping routes open,… Read more »

Thanks, @angelicdespot . Yeah, we tried to build an operational-level framework of the larger campaign, this way we had realistic objectives to fight over instead of “capture the flag” kind of thing. The trick is to set up a supply, logistics, airpower, and shipping “environment” that at least somewhat resembles the actual conditions of the time. This way the campaign aspect of the game more or less runs itself, allowing players to focus on the tactical action. The other trick is to keep that framework from getting too detailed or complicated so it doesn’t slow down the game. 🙂