Roll For Insight: Filching From Folklore

July 26, 2019 by dracs

When we create a world for a game we draw upon a wide variety of different resources. Often, as Ben discussed in the last Roll For Insight, we look to our favourite authors; people like Tolkein, Lewis, Le Guin, or Herbert. However, there is one resource that we all draw upon, and which those authors themselves made heavy use of within their own works: Folklore.

Every culture throughout the world has a rich selection of myths, legends, and folklore that has developed throughout their history. From these, we get magnificent stories of heroes, gods, spirits, monsters, magic, and all manner of other wonderful things with which to colour and populate our image of the world.

These are then woven together to create a fantastic pool of ideas which we can dip into. So, for this Roll For Insight, we are going to journey once again into a world shaped by stories and look at the various ways we can use folklore in our games.

What Is Folklore?

Before going any further, it might be helpful to define what exactly I mean when I talk about folklore. This is more difficult then it might sound, as the question “What is and isn’t folklore?” is one that will likely leave most folklorists and anthropologists rambling happily to themselves until we have to lock them away in a nice, safe university.

Definitions run the gamut from “the stories a culture tells about itself” to, as one folklorist I once asked told me, “everything, right down to the way people take their shoes off at the door.” Which is eye-opening, and certainly makes you look at the world in a new light, but not exactly helpful in terms of this article.

For my purposes, I am using the term folklore as a catch-all to discuss a culture’s own stories, including its various myths, legends, and folktales. This means anything from Jenny Green-Teeth or the Jack tales, all the way up to many and varied examples of divine arse-hattery that is Zeus. This broad spectrum rather sets the academic in me raging against the walls, but I can probably distract it with a copy of Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable and move on.

Monsters, Magic & More

The first way in which we can draw upon folklore is by using the individual elements of it. Folklore is full of fantastic monsters, heroes, gods, and magical items that we can use in our games. Probably the most common way we see this is with monsters. Just how many games out there have minotaurs in them? Or giants, for that matter? Elves and dwarfs have also become ubiquitous, though rather divorced from their folkloric origins. We have stories full of fascinating monsters that we can set our heroes against.

Plenty of games lift various entities and items from folklore. Malifaux and Bushido, for example, have a long list of recognisable beasties from across Asiatic and European folklore. This includes my personal favourite monster the Penanggalan, a vampiric creature whose head flies around trailing its entrails below.

Other games, like Rising Sun, are largely built around adapting these elements. Mythic Battles: Pantheon may be one of the most direct examples, letting us take direct control of the deities, monsters, and heroes of the Greek pantheon.

This lifting of individual elements to place into a game is something we see a lot and it can be a great place to begin when both creating a world and theme for a game. This works especially well when you have a setting that is flexible enough to allow all these culturally distinct entities to appear within the same space, with the Harry Potter universe, most urban fantasy, or anything by Neil Gaiman for a good example of this.

The figures can act as a familiar short-hand for the players. Almost everyone will have some idea of who Zeus is, so getting to control him in Mythic Battles: Pantheon has a far greater impact than it would have if they had created their own, similar deity. We know what to expect from Zeus, Hades, or Poseidon, and it feels awesome to unleash the full might of Olympus on the tabletop.

However, it is still important to remember that these things don’t exist within a vacuum. Many of them draw from specific fears and beliefs of a given culture and some will have attached preconceptions that your players will bring to them. Using them in a setting that doesn’t fit, or in a way that goes directly against how they are portrayed can become jarring. Plopping down a Grecco-Egyptian Sphinx into an icy tundra, for example, will leave them feeling very out of place.

Implementing Folklore

A better way to approach this, at least in my book, is to use these points of folklore more as touchstones for inspiration. Rather than just cutting and pasting them in, find a way to adapt them so that they inform and fit with the environments and societies you have created. That sphinx, can you think of a reason why it is in a polar tundra? How does it need to be adapted to that setting? Does it have different behaviours from the versions we know? This is something that Warploque do very well, finding new approaches to take on established fantasy stereotypes, with their graven being a particularly creative sub-species of gryphon.

Even Mythic Battles: Pantheon attempts to do this in how it depicts the various entities of Greek Mythology. Sure, you are familiar with Poseidon as god of the sea, but you might not be familiar with him as a literal sea monster! This stamps Mythic Battles own identity onto the character and makes him far more interesting than just a bearded guy with a big fork might have been.

Perhaps the best example of using folklore tropes to inform their own setting is the grandfather of fantasy himself, Tolkien.

It is well known that Tolkien was greatly inspired by his readings of Norse mythology. Parallels can be drawn between Gandalf and Odin, or between Smaug and the dragons from Beowulf and The Völsung Saga. There are some cases in Middle-earth where he straight up lifted pieces from folklore (the names of some of the dwarves, the presence of vampires and werewolves, etc.) but for the most part Tolkien used motifs and elements from established mythological traditions to inform and shape the kind of world he wanted.

Follow The Patterns

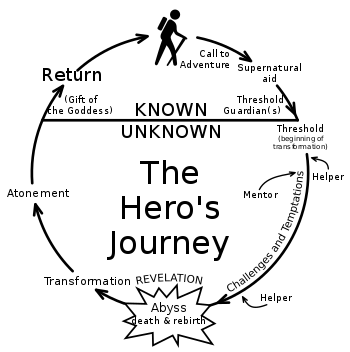

A lot of the stories we find in folklore follow similar patterns and structures. Even when they come from completely disparate societies, we can see similarities. The story of Orpheus’ journey into the underworld, for example, mirrors the story of Izunagi and Izanami from Japan pretty closely. This is something that cultural anthropologists have written on extensively, most famously in works such as the (now discredited) Golden Bough, and The Hero With A Thousand Faces. This is best summed up in the concept the monomyth, or The Hero’s Journey, which points out the various common stages that many hero-focused stories from world culture adhere to.

Recognising these patterns can be a big help to creators, giving them ways in which to structure a story (either by adhering to it or rejecting it), and setting out a series of beats to aim for. The Hero’s Journey structure lends itself particularly well to plotting out games, as it provides you with specific milestones you know you want to meet.

For example, say you are a GM and you are beginning to plan a new game for a group. They are all starting out fairly low level, this is the start of their characters' time as adventurers and they are setting out on their journey. You know a good place to begin will be with The Call To Action, something that kicks off the story and sends them on their way. This is the moment when R2-D2 plays his message for Luke Skywalker.

After this, we cross the Threshold from a space of familiarity to the unknown, at which point they may come face to face with something determined to bar their path. Once they have overcome this, maybe they will need the help of a mentor character, a Gandalf or Obi-Wan whose guidance (and, usually, subsequent death) will shape their journey.

Each of these stages gives you a handy skeleton which you can then build your adventure around and will allow the story and characters to grow organically depending upon how the players react to them. Will they accept the call to action, or reject it only to find themselves forced beyond the threshold as Luke initially does in Star Wars? Such moments will inform the character's attitudes and development as the game progresses.

Recognising these patterns can be helpful as a player, as well as a game creator or GM. If you are starting out as a low-level hero, it might be helpful to talk over the tropes with the GM so together you can plot how you would like to see the character develop.

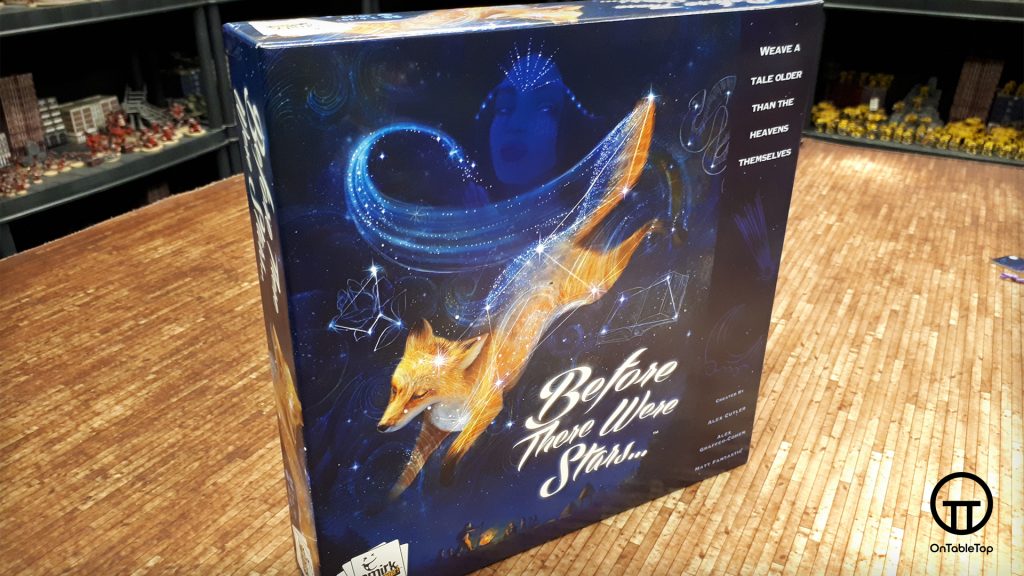

Perhaps the best example I have come across of how useful knowing these patterns as a gamer can be was during a recent game with Ryan and Cass of Before There Were Stars.

Ryan has talked about this game extensively in one of his previous Roll For Insight articles, and it has swiftly become one of my all-time favourite board games. The idea is simple: you and your friends take on the role of story-tellers passing down oral myths and legends. You draw cards for each phase of story-telling and have to weave your tale depending on what you find on the cards.

For me, when it came to creating my stories, I tried my best to stick closely to the patterns I know are common to many myths. I knew what sort of things I could put into a Creation Myth (pretty much anything, they are gloriously bizarre), what I needed to do for A Hero Rises, the Birth of Civilisation, etc. In the end, I was able to create a story that, I felt, managed to flow surprisingly well and hit enough familiar points to make it sound authentic.

Do Your Research

At the end of the day, being able to effectively use folklore to enhance your games really boils down to doing your research. As I said before, none of these stories or traditions exist in vacuum. If you just choose to use some of the surface aesthetics of a culture without any of the deeper meaning or importance that lies behind them, you can come away with some extremely lazy stereotypes that swiftly become pretty problematic (looking at you, early 90s World of Darkness).

This is not to mention those occasions where a game thinks they are including a mythical entity from a long-standing tradition, only to find out that they’ve fallen to a Wikipedia prank by some guy from New Zealand.

Researching folklore is an incredibly rewarding experience, and one that will spark more and more ideas the more time you devote to getting to grips with it and understanding it further. Once you have that basis of understanding, you can find new ways in which to view it and new stories to tell with it.

What are some of your favourite folklore tales from your corner of the world?

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

![How To Paint Moonstone’s Nanny | Goblin King Games [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/12/3CU-Gobin-King-Games-Moonstone-Shades-Nanny-coverimage-225-127.jpg)

I enjoyed reading that! Possibly this is due to ignorance more than anything else but for me the Ulster Cycle of Irish Mythology and Irish Mythology in general is perhaps a much under explored area in the world of gaming. Of Gods and Mortals by Osprey touches on it with its Celtic army list, but I am not aware of many others. Tolkien’s influences is an interesting one and an article in itself, and while you correctly highlight Norse mythology, Anglo-Saxon was possibly as big an influence as Norse. Though if I remember rightly, many dismiss the influence of Celtic… Read more »

Scion uses elements from it. You can make characters descended from the Tuath de Danaan and give them a geas or even cuchulain’s riastradh

Thanks for the info and the great article!

Arthurian myths and Robin Hood have been with me since childhood and over the years I have a number of cinematic incarnations of both of them. When I first started playing D&D and ran my first cleric I encounter Deities and Demigods. In it the Greek Pantheon stood and after extensive background reading decided that it made a lot more sense than the young religions… the ones commonly worshipped now. The Greeks were fun… they had weaknesses, vices, personality quirks, friends, enemies… they seemed more human… more than human… they were a soap opera… It made a lot more sense… Read more »

Great article @dracs . Obviously this is something we cover a lot on Darker Days Radio with the secret frequency. Something you have missed is modern folklore in the form of urban legends and creepypasta. These are our modern horror legends and fairy tales – the most renowned being old Slenderman himself.

The secret frequency is my favourite part of the show. And yes urban legends and creepy pasta could be an article to themselves. If you haven’t already, I’d thoroughly recommend The Folklore Podcast (run by the British Folklore Society) episode on Slenderman.

This is good article. Folklore tends to be good source and Tolkien’s books (Hobbit, LotR and Silmarillion) that form basis of modern fantasy has it’s roots in several folklore. Norse, Kalevala and Irish folklore all had they influence on Tolkien’s books including languages that he created for races living on Arda and Middle Earth. In gaming all different folklore have potential to influence several settings and already have. Even some video games have already been either influenced by those or even uses those.

Speaking of Beowulf – this is very interesting radio programme featuring 3 academics discussing the poem – really worth a listen – https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b0542xt7

the thing is with folklore many of the story’s are scarier than any film I have seen a the beasty may live in the hill n trees you live or word beside.

Ah but begs the question who is Tolkein lol

Folklore is as important to us in a modern world as it has ever been. It is used though, i feel, as escapism rather than allegoric in mainstream media and, to an extent, games. The cultures of our past telling stories of great, terrible and mythical creatures and battles are a gift. In 2019, what are we leaving for those folklorists and anthropologists a thousand years from now. “The terrifying Beast known only as Huawei stealthily undermined all who paid no heed to the dangers. The Samsung would erupt in flames, never reborn, just replaced!. While the IPhone would light… Read more »

I currently have a copy of The Woods sitting beside my desk. Unfortunately, I haven’t had a chance to dig through it yet.