Napoleon in Egypt – Expédition Baïonnette en Argent

Recommendations: 441

About the Project

Exploring Napoleon's Egyptian adventure via the Silver Bayonet. The intention is to try and keep the historical side relatively accurate to allow models to be used for pure historical games, whilst mixing in the more horrific beasties and monsters.

Related Game: The Silver Bayonet

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

Giant Scorpion

Second big beastie is a giant scorpion, again coming from Northstar. The painting was again pretty quick and simple, mostly done with drybrushing over a dark base coat with an odd wash and glaze, and a couple of highlights picked out at the end.

Bit more effort to assemble than the snake, as the claws and tail are weighty bits of metal that really need pinning, but it certainly looks the part when placed up against 28mm figures.

Uraeus

Time to add a few more monsters to my Silver Bayonet: Egypt bestiary. First up is a Uraeus (or really big snake to the lay person). The model comes from the official Northstar range, and is a relatively easy built multi-part metal figure. As the last picture shows, the figure is a good size, with snake rearing comfortably above a 28mm figure.

I kept the painting pretty simple, avoiding anything too elaborate with patterning.

French Command Group

A few more Frenchmen all painted up. These chaps come from the 85eme demi brigade. At this point I’ve got substantially more than the 8 figures required for a Silver Bayonet unit, but choices are very important (that’s my excuse anyway), and there’s another officer/junior officer plus a sappuer here.

All figures are from Brigade Games again, flag is from GMB Designs.

Camel Holder

Since I’ve got both Dromedary Corps troopers on camels and their dismounted counterparts, it seemed necessary to also have a camel holder.

This set is by the Perrys, which are a bit larger than the Brigade Games figures, but I think they look okay alongside each other.

I’ve also picked up a couple of the Gale Force 9 Battlefield in a Box sets, with the fallen column belonging to one of them. I’m quite impressed with them, nice pieces that save me a bit of time making/painting my own equivalents.

Ottoman Water Carrier

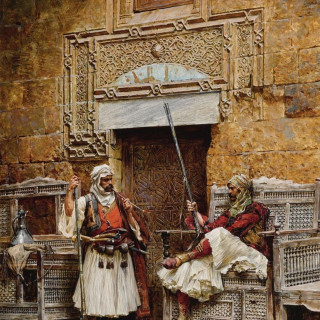

Albanian Soldiers

Back to painting humans rather than the supernatural monsters with some Albanian soldiers. Rather than being part of the French Armée d’Orient like the others in this project so far, these chaps are part of the Ottoman army.

I found quite a few variations on clothing colours for these troops. Whilst the white pleated skirt-like garment (called a fustanella) is very standard, jackets are depicted in several colours, mainly green or red, often with a lot of embellishments and details. Paintings by Paja Jovanovic caught my interest the most (see the two examples below), so I based my colour schemes around these (although passed on the detailing).

No idea how historically accurate these are, but I quite like the end look of bright red against the white.

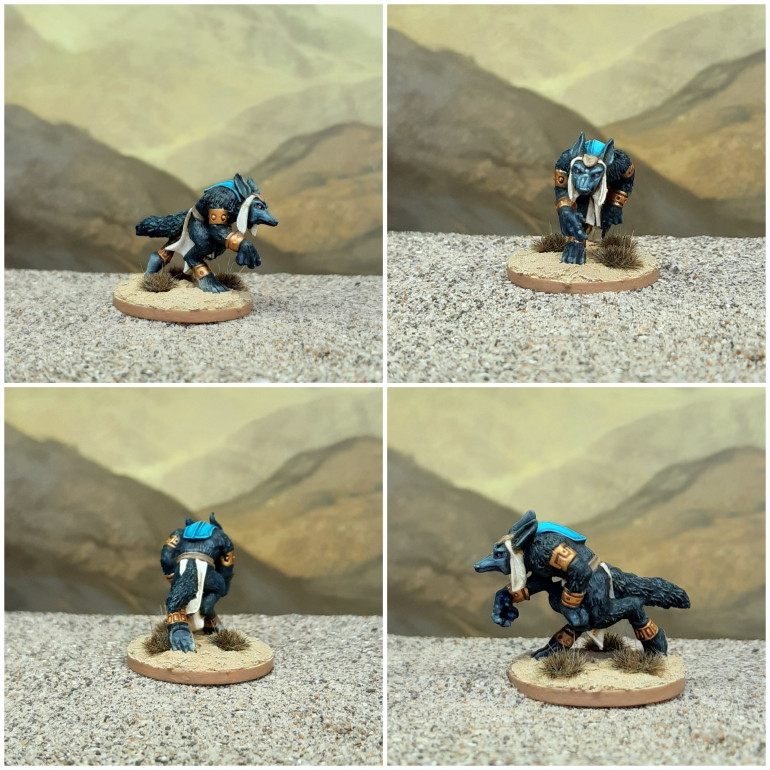

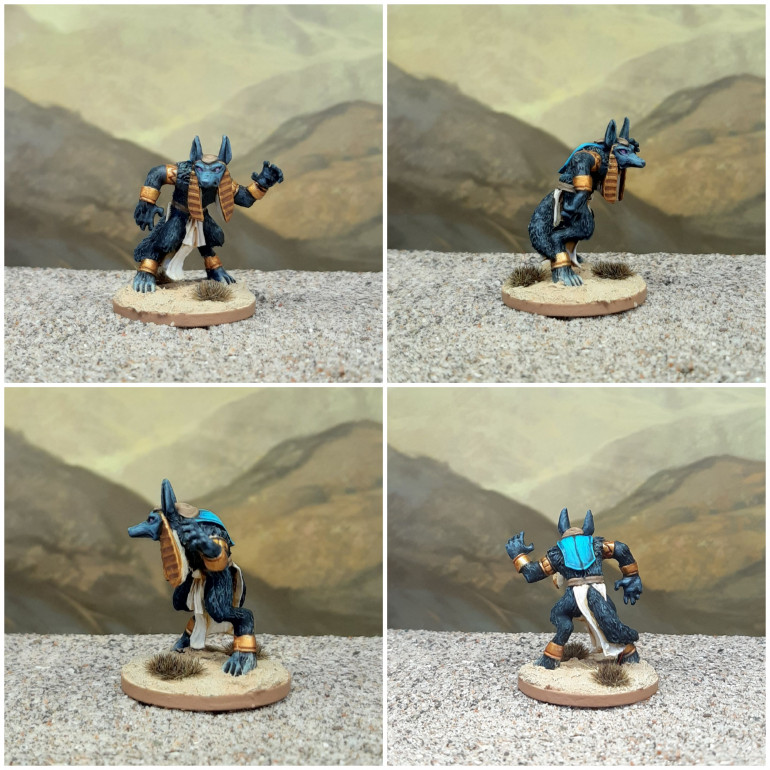

Werejackels

Another of the new monsters for Silver Bayonet: Egypt are werejackels, with a pair of nice sculpts produced by Northstar to accompany the new supplement.

Serpopard

These dangerous creatures have the body of either a lion or leopard but with a long, snake-like head, which writhes and twists with strangely hypnotic movements.

One of new monsters for the Egyptian supplement, the Serpopard has a very characterful sculpt via Northstar. I had a bit of fun trying out a spot pattern, which I’m pretty happy with. Probably should have consulted with a reference picture of big cat patterns first, but why worry too much for a mythical beast?

Scarab Swarms

A couple more swarm bases to join the rats, this time scarab beetles.

These come from Northstar, originally part of their Frostgrave range I think. Still, they look the part as generic large bugs.

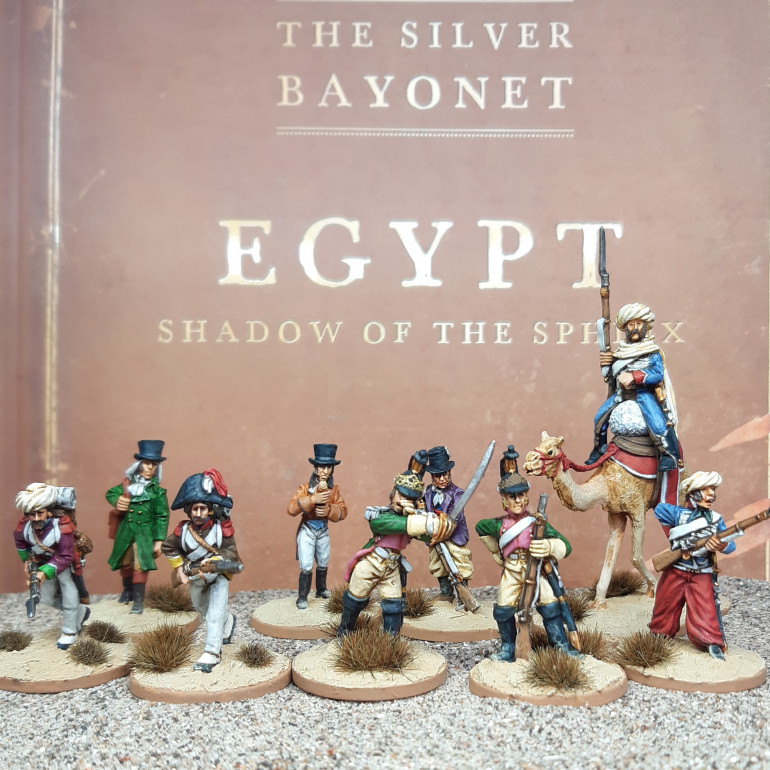

French Unit Ready for Action

The Silver Bayonet: Egypt book arrived this week, along with a few of the new monsters from Northstar.

Whilst the beasties are joining my painting queue, I thought I’d put together a French unit from the models I have painted in this project.

As arranged from left to right in the image above –

- There is a Grenadier from the 88eme demi brigade;

- A Doctor from the recently established Egyptian Institute of Arts and Sciences;

- Another Grenadier, this time from the 85eme demi brigade

- A Supernatural Natural Investigator, also from the Institute, but shunned for his less reputable academic studies;

- The Officer, hailing from the 15eme dragoons;

- A Sailor, left ashore after the Battle of the Nile wrecked the French navy;

- A dragoon trooper from the 15eme, following his officer;

- Finally, a mounted/dismounted trooper from the Dromedary Corps.

The dragoon trooper will represent a Soldier, whilst the dromedary trooper will be a Light Cavalryman.

Really happy at the colourful attire sported by this lot.

Rat Swarms

Continuing to bulid my bestiary with a couple of rat swarms from Midlam Miniatures.

The Mummy

Time for the first of the monsters and supernatural horrors that will plague the French. The obvious starting point is with a mummy.

This model is from Midlam Miniatures, and I just loved the sculpt and the slight departure from the traditional Holywood-look mummy. It does stand pretty tall though, and absolutely towers over the 28mm French, which is absolutely fine with me – a suitably imposing horror.

Really quick and simple painting here. Base coat of Vallejo Buff, wash with Vallejo Sepia wash, drybrushed with Buff, and then a lighter drybrush with Vallejo Ivory. It won’t win any prizes, but I’m happy at how fast it was to finish.

Grenadiers

Seeing the pre-orders and teasers for the upcoming release of the Silver Bayonet Egypt prompted me to take a break from Spring Cleaning and return to this project.

These are French line grenadiers wearing Kleber ordnance, a pair from the 88eme demi-brigade and a pair from the 85eme. Rather than the usual blue jackets, the Kleber ordnance is much more colourful. The 88eme had violet jackets with green cuffs and blue collars, whilst the 85eme had brown jackets with yellow cuffs and red collars. Other demi-brigades had red, green or sky-blue jackets. Essentially, the Kleber ordnance is perfect for something like the Silver Bayonet as your basic soldiers can all have distinctively coloured uniforms whilst still satisfying any button counting tendencies.

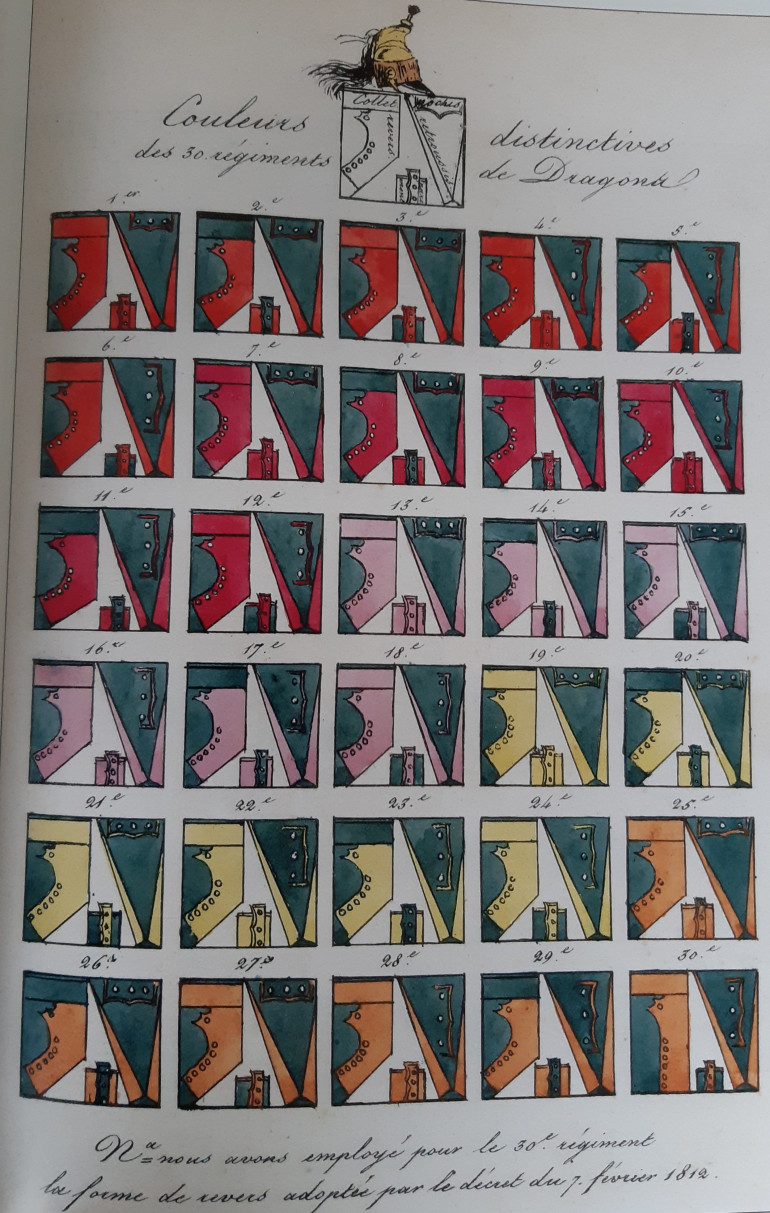

Dragoons

Dismounted French Dragoons are next to join my Armée d’Orient. I liked the idea of maybe using these as the standard ‘Soldier’ troop type for Silver Bayonet units, with the leader a potential Officer figure.

These have been painted in the colours of the 15e Regiment of Dragoons. Napoleonic French Dragoon regiments were grouped by facing colours, with slight differences between regiments as to whether collars, cuffs, lapels, lacing etc. appeared in green or their regimental colour (image below for thise with the interest in such detail). The 15e were a pink faced regiment, and thanks to the long gloves worn by the models, I didn’t have to worry about remembering the green cuffs. I stuck with green coats, although there are records of lack of supplies meaning many ended up dressed in undyed cloth.

Besides having fun painting the poppy pink, another reason for painting these as the 15e was their long boots, a uniform feature noted as being particular to that regiment (according to Perrys’ website anyway!). I went with a typical reversed colours for the trumpeter, although I’ve no idea if that is accurate.

All figures are again Paul Hicks sculpts sold by Brigade Games, with image backgrounds by John Hodgson via one of his backdrop books.

More Dromedary Corps (this time with camels)

Three mounted troopers of the Dromedary Corps to go with their dismounted equivalents in the previous entry.

There’s lots of sources that depict the camel furniture in a wide variety of different colours, with the cloth hanging from the saddle in particular being illustrated in lots of colours and highly embroidered/decorated. I decided to be a bit restrained and went with the regimentally proscribed red cloth with white edging.

Dismounted Dromedary Corps

My first finished models for 2024 are these trio of dismounted Dromedary Corps troopers.

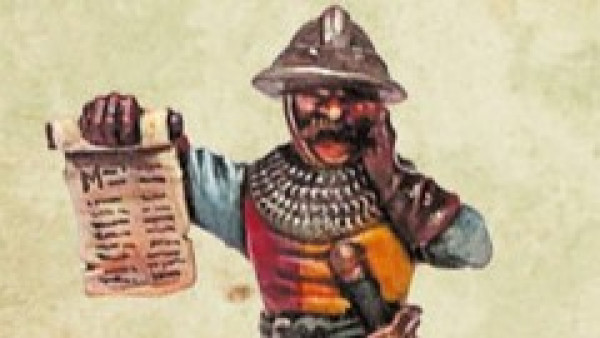

The Regiment de Dromedaries was raised by Napoleon after landing in Egypt in 1799, and disbanded at the end of the Egyptian campaign. At its largest, the unit had around 700 men split into three squadrons, although not all were mounted. They most likely fought as mounted infantry, and were used for scouting, escort and message delivery roles.

Their uniforms had many variations. They wore sky blue dolman and breeches, with red cuffs and collar on the jacket and white hussar style braiding. Dress uniform included a red kaftan worn over the dolmen. Initially they wore a white turban, replaced by a black bicorn in 1800. White Turkish style trousers were also worn, which were replaced by dark red Turkush style trousers after Kleber’s uniform changes.

One of the things that drew me to these Brigade figures is that offer the chance to depict quite a few of these uniform differences. None wear the red kaftan, but I took the opportunity to have both white and red Turkish style trousers. One has a turban, the other two bicorns. This ends up in three nicely unique individuals, important for skirmish games.

Next up will be their mounted equivalents, which means working out how to paint camels.

Scientists & Savants

The Army of the Orient was not only a military force, being accompanied by scientists, archaeologists and administrators to conduct research and to determine the potential of Egypt as a French colony.

Bonaparte established the Egyptian Institute of Arts and Sciences in Cairo, August 1798. The principal objectives of the Institute were the ‘progress of knowledge and its propagation I Egypt’, ‘Research, study and publication of the natural, industrial and historical facts about Egypt’, and ‘To give advice on the various questions upon which it may be consulted by the Government.’

These figures are in civilian clothing, with a couple based on a picture by Bob Marrion. They will be used for the more civilian-type troop choices in the Silver Bayonet, such as Doctors, Occultists and Supernatural Investigators. They can also have potential as clue markers, particularly the sitting chap.

The Egyptian Institute was responsible for finding the Rosetta Stone in 1799, but it was given up to the British as part of the terms of French capitulation in 1801.

French Sailors

First models painted are some French sailors. Both the French and the British landed troops in amphibious assaults during the Egyptian campaign, with sailors and marines supporting army units.

Post Battle of the Nile, those French sailors that survived the loss of the fleet were formed into an infantry regiment called the Legion Nautique. My figures aren’t wearing the uniforms of the Legion, which had short red coats and round black hats.

Instead they have typical sailor outfits, which I’ve broadly painted according to the colours of the French navy. One was inspired by a picture by Bob Marrion, based on a contemporary description of seaman wearing “a lilac coloured short coat with a red sash, plus varnished round hat.” I also gave one striped trousers, since it’s a commonly depicted thing for sailors from the period.

A Historical Digression and a Discussion on Uniforms

Another wall of text post whilst I start getting paint on figures.

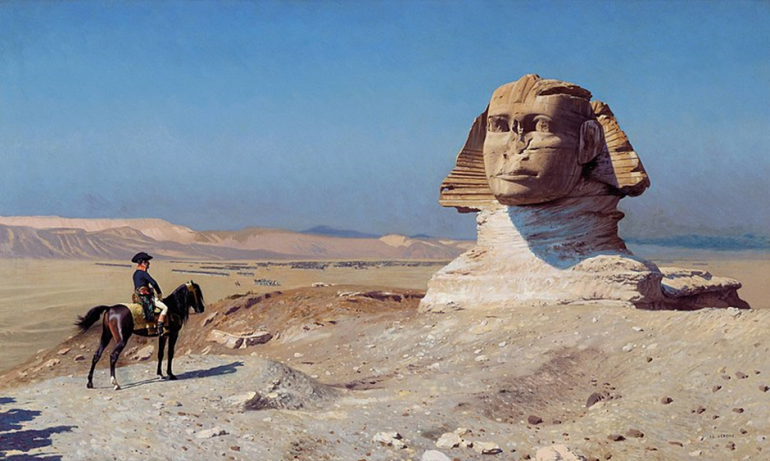

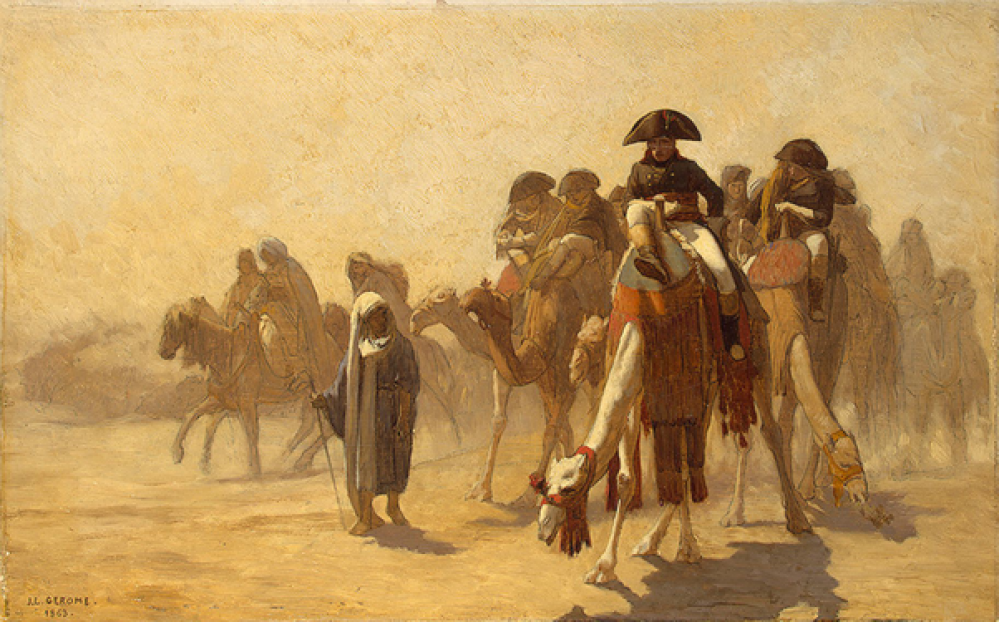

Strictly speaking, Napoleon’s misadventures in Egypt aren’t part of the ‘Napoleonic Wars’. The French campaign in Egypt ran from 1798-1801, with Bonaparte leading the expedition as a General of Revolutionary France under the Directory. But we’re going to ignore that distinction for the duration of this project.

I’m going to include a short summary of the campaign for anyone unfamiliar with it, starting with why the French were in Egypt in the first place. There were a few different factors at play. Politically, there was the desire of the Directory to put some distance between Paris and a dangerously powerful military man, who was flushed with his spectacular success in Italy. There was also interest from both the Directory and Napoleon to attempt to remove Britain’s powerbase on the Indian sub-continent, whilst avenging losses from the Seven Years War, notably Canada and the colonies in the Indies.

The French Army of the Orient assembled at several Mediterranean ports, with Napoleon departing from Toulon in May 1798 at the head of ~36,000 men. They managed to dodge the Royal Navy, who were aware of the preparation for an invasion and were looking to intercept any French fleet, but scattered by a gale that allowed the French to depart Toulon unmolested. The French captured Malta on their way to landing at Aboukir Bay in Egypt, before marching on Alexandria. From Alexandria, the French marched to Cairo, defeating the Mamluks at the Battle of the Pyramids in July 1798.

At this point the Royal Navy finally caught up with French fleet, Admiral Nelson finding them anchored in a strong defensive position in Aboukir Bay. Nelson demonstrated his characteristic boldness, ordering his fleet to attack, slipping half of his ships in between the land and the French line, thus attacking from both sides. The Battle of the Nile was perhaps the worst French defeat of the whole Napoleonic period. The British suffered paltry casualties (no ships lost; ca.200 dead & 700 wounded), whilst the French lost eleven warships and two frigates, with only two warships and two frigates escaping. Unlike at Trafalgar, the results of battle were felt immediately. Without a fleet in the Mediterranean, France could no longer run the Egyptian campaign satisfactorily. Malta subsequently returned to British control. The Turks declared war on France on 4th September, and as a result of the lack of naval support Napoleon was to meet with failure at the siege of Acre, and his army struggled with supply issues for the remainder of the campaign.

The French set about consolidating their foothold in Egypt, quelling an uprising in Aciro, and Desaix pursing the Mamluk’s into the upper Nile area. In 1799, Napoleon attempted to counter an Ottoman attack into Egypt by invading Syria. The Syrian campaign concluded with the failed siege of Acre, an interesting siege in that the French held none of the typically advantages of a besieger, yet still persisted with the attempt – they were outnumbered by the defenders, lacked siege artillery, and had poor supply lines (whilst Ace was re-supplied by sea by the Royal Navy). The French retreated back to Cairo, with 1,800 wounded, having lost 600 men to the plague and 1,200 to enemy action.

In July 1799 a Turkish fleet landed an army in Aboukir, with the French engaging them in a land battle. This was Napoleon’s last action in Egypt. His army was diminishing from losses in battle and disease, difficulties in resupply were paramount, and there was news of political instability at home. He abandoned the Army of the Orient in August 1799, accompanied by some of his favoured generals (Berthier, Murat, Lannes and Marmont), leaving General Kleber to command those left behind. From 1800-1801 the British combined with the Ottomans in a land offensive that defeated the French, who finally capitulated in 1801.

Onto uniforms then, specifically French uniforms. The Egypt campaign has essentially three different phases of uniforms for the French.

- The uniform at the initial embarkation of the expedition.

- Changes to the uniform in Egypt to adjust to local materials and supplies.

- The Kelber Ordnance.

The first phase is essentially the uniform of the French Revolutionary armies – long tailed blue coats, bicorns, tricolour trousers and patriotic zeal aplenty.

In 1799 the troops were issued with distinctive leather helmets called petit casquettes, and indigo dyed cotton uniforms were issued alongside loose white trousers to replace their breeches.

Which brings us to the Kleber Ordnance 1799, or where the uniforms really diverge from the usual colours that you’d expect to see on a French soldier. After Napoleon abandoned his army, Kleber was left in charge of the expedition, cut off from supply lines back to friendly territory by the British Navy. Kleber had to make do with whatever material he could find locally to cloth and uniform the French soldiers. This resulted in a variety of very colourful coats for the French infantry, some wearing scarlet coats, others crimson, sky blue, light green, brown and violet – essentially, a very different looking army to the blue coated French that are typical of the period. There’s great scope within a small skirmish game like Silver Bayonet to have an excuse to capture a lot of this variety, so I will be exploring some of the different infantry uniforms of the Kleber Ordnance within this project.

The British army contained contingents from India and troops from South Africa, not to mention marine regiments on land and various German companies, so there is lots of opportunity to build a very diverse and interesting collection focused on this campaign. The Ottomans and Mamluks also have very interesting armies for this area, with very bright and elaborate uniforms. But at the start of this project, I’ll be concentrating on the French.

Getting Started

The start of this project very much mirrors my other Silver Bayonet project. Back when the Silver Bayonet was first announced, I was very intrigued and started having a nose at possible models, looking for potential individual characters from the typically mass ranked figures that (understandably) comprise the majority of Napoleonic miniature ranges. Very quickly I got locked onto the Perrys’ Retreat from Moscow figures; very individual, dynamically posed characters, perfect for a small unit, and giving an interesting theme to set my game within (with the added benefit of 1812 Russia being very different to my Peninsula Napoleonic collection). The idea was to keep the ‘historic’ aspects fairly accurate, and then add in the more fantastical/horror elements with the monsters, giving me the option of also using the soldiers for other Napoleonic games.

Fast forward to now, and a similar thing has happened with the upcoming Silver Bayonet: Egypt book. Joseph McCullough spoke about the expansion in some interviews with OTT in September, which got me looking into what figures are available for this period of Napoleonic warfare. Although the Perrys do have a very nice range of French in Egypt models, and a lovely new range of Ottomans, the models that caught my eye were from Brigade Games in the US –figures sculpted by the very talented Paul Hicks. One of the draws is that some of Paul’s mounted figures have dismounted equivalents based on the same individual models, a pretty important thing for a skirmish game where a cavalry model needs both mounted/on foot versions. The other draw was simply the very characterful sculpts, which also represent a lot of the things I was looking for – officers, camelry, scientists, soldiers, some irregulars as possible bandits…

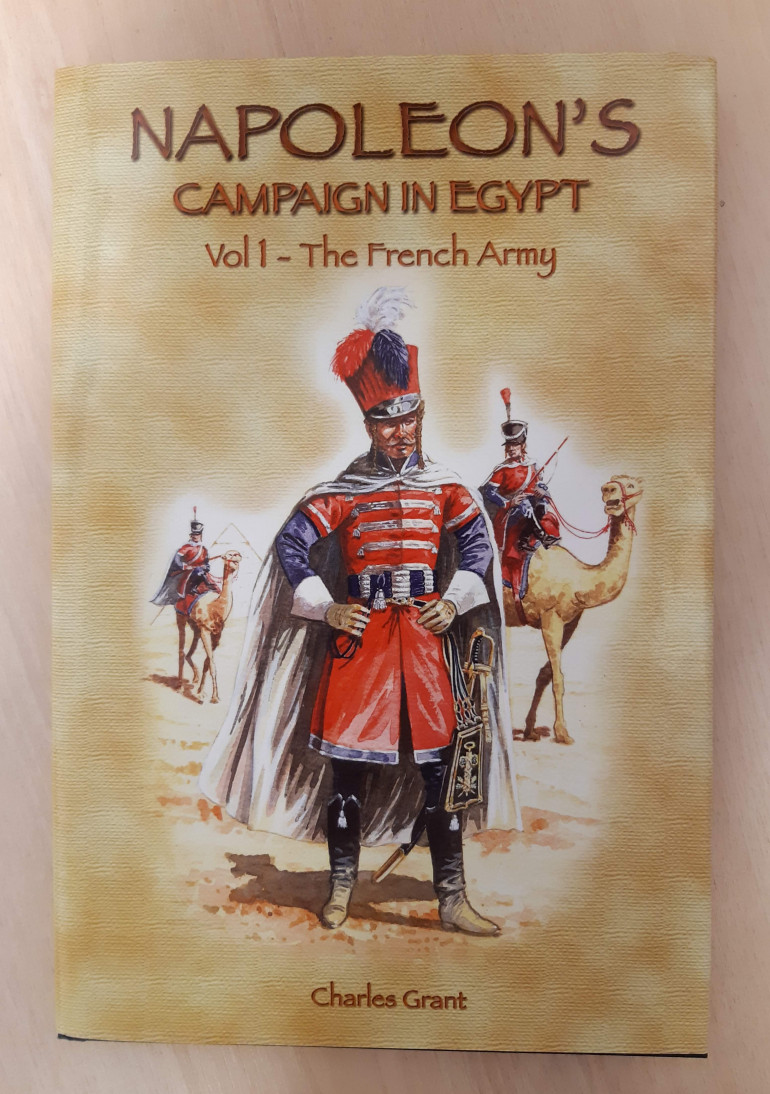

In terms of research for the period, I’m using a pair of books – Napoleons’ Campaigns in Egypt Vol. 1 & 2 by Charles Grant. The former covers the French, whilst the latter details the British, Egyptians and Ottomans. Each volume is filled with superb illustrations by Bob Marrion, which are going be used as guides and inspiration for painting.

As per my other Silver Bayonet project, the goal is to try for a relatively high level of historical accuracy on the figures, and then add in the beasties and other supernatural elements. As of yet, I’ve no idea what types of monsters might be necessary for the Egypt setting, other than Joe mentioning crocodiles. I’ll also need to make up some new clue markers.

![How To Paint Moonstone’s Nanny | Goblin King Games [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/12/3CU-Gobin-King-Games-Moonstone-Shades-Nanny-coverimage-225-127.jpg)